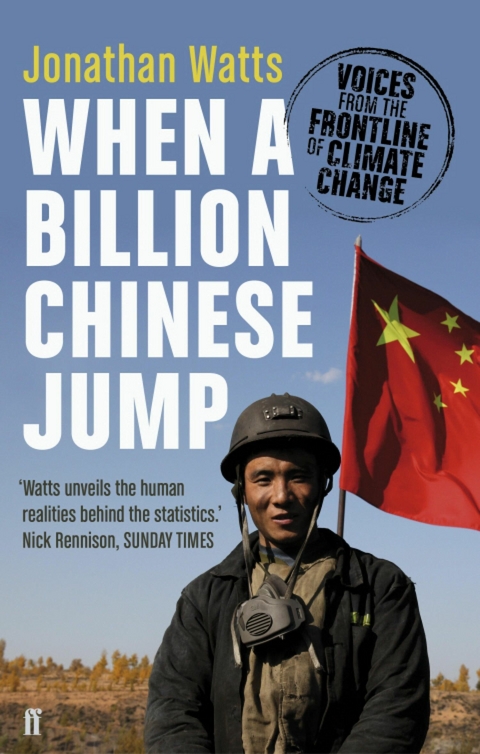

When a Billion Chinese Jump (eBook)

496 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-25867-3 (ISBN)

Jonathan Watts is the Guardian's Asia environment correspondent and recently covered the Copenhagen Climate Conference. He was short-listed for Foreign Correspondent of the Year at the 2006 British Press Awards, and he and his research assistant were awarded the One World Media Award for best press story in 2007. In 2009, he was a co-winner of the environment prize at the One World Media Awards for a series on the global food crisis.

When a Billion Chinese Jump tells the story of China's - and the world's - biggest crisis. With foul air, filthy water, rising temperatures and encroaching deserts, China is already suffering an environmental disaster. Now it faces a stark choice: either accept catastrophe, or make radical changes. Traveling the vast country to witness this environmental challenge, Jonathan Watts moves from mountain paradises to industrial wastelands, examining the responses of those at the top of society to the problems and hopes of those below. At heart his book is not a call for panic, but a demonstration that - even with the crisis so severe, and the political scope so limited - the actions of individuals can make a difference. Consistently attentive to human detail, Watts vividly portrays individual lives in a country all too often viewed from outside as a faceless state. No reader of his book - no consumer in the world - can be unaffected by what he presents.

Jonathan Watts is the Guardian's Asia environment correspondent.

As a child, I used to pray for China. It was a profoundly selfish prayer. Lying in bed, fingers clasped together, I would reel off the same wish list every night: ‘Dear Father, thank you for all the good things in my life. Please look after Mum and Dad, Lisa (my sister), Nana and Papa, Toby (my dog), my friends (and here I would list whoever I was mates with at the time) and me.’ After this roll call, the signoff was usually the same. ‘And please make the world peaceful. Please help all the poor and hungry people, and please make sure everyone in China doesn’t jump at the same time.’

That last wish was tagged on after I realised the enormousness of the country on the other side of the world. For a small British boy growing up in a suburb of an island nation in the 1970s, it was not easy to grasp the scale of China. I was fascinated that the country would soon be home to a billion people.1 I loved numbers, especially big ones. But what did a billion mean? An adult explained with a terrifying illustration I have never forgotten. ‘If everyone in China jumps at exactly the same time, it will shake the earth off its axis and kill us all.’2

I was a born worrier and this made me more anxious than anything I had heard before. For the first time, my young mind came to grips with the possibility of being killed by people I had never seen, who didn’t know I existed, and who didn’t even need a gun. I was powerless to do anything about it. This seemed both unfair and dangerous. It was an accident waiting to happen. Somebody had to do something!

Life suddenly seemed more precarious than I had ever imagined. In variations of my prayer, I asked God to make sure that if Chinese people had to jump, they only did it alone or in small groups. But in time, my anxieties faded. With all the extra maturity that comes from turning eight years old, I realised it was childish nonsense.

I did not think about the apocalyptic jump again for almost thirty years. Then, in 2003, I moved to Beijing, where I discovered it is not only foolish little oiks who fear China leaping and the world shaking. In the interim, the poverty-stricken nation had transformed into an economic heavyweight and added an extra 400m citizens. China was undergoing one of the greatest bursts of development in history and I arrived in the midst of it as Beijing prepared for the 2008 Olympics.

The city’s transformation was vast and fast. Down went old hutong alleyways, courtyard houses and the ancient city walls. Up rose futuristic stadiums, TV towers, airport terminals and other monuments to modernisation. Restaurants and bars one day were piles of rubble the next. Tens of thousands of old walls were daubed with the Chinese character chai (demolish). The hoardings around a nearby development site were decorated with giant pictures of the old city and a half-mocking, half-mournful slogan: ‘Our old town: Gone with the wind.’

Living amid such a rapidly shifting landscape, it was hard to know whether to celebrate, commiserate or simply gaze in awe. The scale and speed of change pushed everything to extremes. On one day, China looked to be emerging as a new superpower. The next, it appeared to be the blasted centre of an environmental apocalypse. Most of the time, it was simply enshrouded in smog.

Soon after arriving, I walked home before dawn one morning in a haze so thick I felt completely alone in a city of seventeen million people. The milky white air was strangely comforting. Skyscrapers had turned into thirty-storey ghosts. The world seemed to have vanished. Yet it was also being remade. Overhead, cranes loomed out of the mist like skeletal giants.

Over the following years, the crane and the smog were to become synonymous in my mind with the two biggest challenges facing humanity: the rise of China and the damage being wrought on the global environment. The builders were constructing the most spectacular Olympic City in history. The chimney emissions and car exhausts were destroying the health of millions and helping to warm the planet as never before.

The year after my arrival, China’s GDP overtook those of France and Italy. Another year of growth took it past that of Britain – the goal that Mao Zedong had so disastrously set during the Great Leap Forward fifty years earlier. From 2003 to 2010, China stopped receiving aid from the World Food Programme and overtook the World Bank as the biggest investor in Africa. Its foreign-exchange reserves surpassed those of Japan as the largest in the world. The former basket-case nation completed the world’s highest railway, the most powerful hydroelectric dam, launched a first manned space mission, sent a probe to the moon and moved to the centre of the global debate about climate change.

This was a period in which the population increased at the rate of more than seven million people per year, when more than seventy million people moved into cities, when GDP, industrial output and production of cars doubled, when energy consumption and coal production jumped 50 per cent, water use surged by 500bn tons and China became the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide and pollution in the world.3

As a parent, I worried for my two daughters’ health when the air became so bad that their school would not let pupils out at break times. I feared too for my lungs. A regular jogger since my teens, I found myself wheezing and puffing after even a short run. When the coal fires started burning each winter, I suffered a dry, rasping cough that sometimes left me doubled up. In Beijing I was to suffer two bouts of pneumonia and, for the first time in my life, I was prescribed a steroid inhaler. The city was choking and so was I.

To be in Beijing at this time was to witness the consequences of two hundred years of industrialisation and urbanisation, in close up, playing at fast-forward on a continent-wide screen. It soon became clear to me that China was the focal point of the world’s environmental crisis. The decisions taken in Beijing, more than anywhere else, would determine whether humanity thrived or perished. After I arrived in Beijing, I was first horrified at the chaos and then excited. No other country was in such a mess. None had a greater incentive to change.

The environment had become a national security issue and the government started to respond. The leadership – the hydroengineer Hu Jintao and the geologist Wen Jiabao, or President Water and Premier Earth, as I came to think of them – started to shift the communist rhetoric from red to green. They wanted science to save nature. Instead of untrammelled economic expansion, they pledged sustainability. If their goals were achieved, China could emerge as the world’s first green superpower. Alternatively, if they failed and the world’s most populous nation continued to leap recklessly onward, our entire species could tip over the environmental precipice.

These were the extremes. The truth was probably somewhere in between – but where? That became the biggest question of my time in China. For the first five years as a news correspondent for the Guardian, the environment was my primary concern. After that, it became such an obsession that I took six months off for private research trips and then returned to a new post as Asia environment specialist. Travelling more than 100,000 miles from the mountains of Tibet to the deserts of Inner Mongolia, I witnessed environmental tragedies, consumer excess and inspiring dedication. I went to Shangri-La and Xanadu, along the Silk Road, down coal mines, through dump sites and into numerous cancer villages. I saw the richest community, the most polluted city and the foulest sea. On the way I talked to leading conservationists, politicians, lawyers, authors and China’s top experts on energy, glaciers, deserts, oceans and the climate. Most compelling were the stories of ordinary people affected in extraordinary ways by a burst of human development the like of which the world had never seen before.

This, then, is a travelogue through a land obscured by smog and transformed by cranes; one that examines how rural environments are being affected by urban consumption. What are we losing and how? Where are the consequences? Can we fix them? It projects mankind’s modern development on a Chinese screen.

The chapters progress through regions and themes to show the diversity of ecologies, economies and cultures at play, but the structure of the book is polemical rather than geographic. When I had to choose between a strong case study and a line on the map, I opted for the former even if that occasionally meant leapfrogging provinces, returning to some places twice, and cutting across boundaries. Lest anyone fear that I am asserting a new territorial claim by Dongbei on Inner Mongolia, or by the southeast on Chongqing, I should state their place in these pages is determined by the powerful trends they illustrate. Similarly, my apologies to anyone who feels slighted or frustrated by my selective approach. Omission of a province is not intended to dismiss its importance any more than inclusion is meant to indicate a paradigm case.

The choice of location and topics in these pages is determined purely by my own experience. Even over many years and miles, that is limited. China is simply too vast and changing too fast to capture in its entirety. Yet even fragments tell a story. Starting from the world’s high, wild places and descending into the crowded polluted plains, the book tracks mankind’s modern progress and my own growing realisation: now China has jumped, we must all rebalance our...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.9.2010 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Öffentliches Recht | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Cities • civilisations • Environment • Globalisation • global warming • Travelogue |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-25867-0 / 0571258670 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-25867-3 / 9780571258673 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich