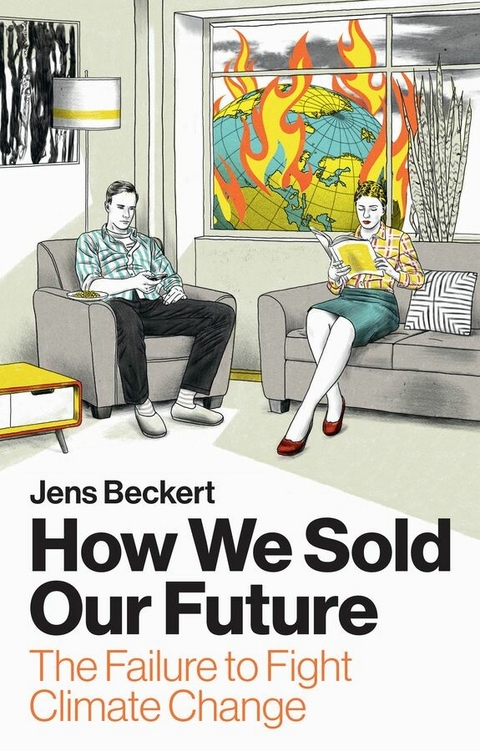

In this important new book, Jens Beckert provides an answer to these questions. Our apparent inability to implement basic measures to combat climate change is due to the nature of power and incentive structures affecting companies, politicians, voters, and consumers. Drawing on social science research, he argues that climate change is an inevitable product of the structures of capitalist modernity which have been developing for the past 500 years. Our institutional and cultural arrangements are operating at the cost of destroying the natural environment and attempts to address global warming are almost inevitably bound to fail. Temperatures will continue to rise and social and political conflicts will intensify. The tragic truth is: we are selling our future for the next quarterly figures, the upcoming election results, and today's pleasure. Any realistic climate policy needs to focus on preparing societies for the consequences of escalating climate change and aim at strengthening social resilience to cope with the increasingly unstable natural world. Civil society is the only source of pressure that could build the necessary strength and support for climate protection.

How We Sold Our Future is a crucial intervention into the most pressing issue of our time.

Jens Beckert has been Director at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies and Professor of Sociology in Cologne since 2005. He previously taught in Göttingen, New York, Princeton, Paris, and at Harvard University. In 2018 he received the German Research Foundation's Leibniz Award, the highest research award granted in Germany. For his book Imagined Futures he received the Karl Polanyi Prize from the German Sociological Association. His other books include Inherited Wealth and Beyond the Market.

For decades we have known about the dangers of global warming. Nevertheless, greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase. How can we explain our failure to take the necessary measures to stop climate change? Why are societies, despite the mounting threat to ourselves and our children, so reluctant to take action?In this important new book, Jens Beckert provides an answer to these questions. Our apparent inability to implement basic measures to combat climate change is due to the nature of power and incentive structures affecting companies, politicians, voters, and consumers. Drawing on social science research, he argues that climate change is an inevitable product of the structures of capitalist modernity which have been developing for the past 500 years. Our institutional and cultural arrangements are operating at the cost of destroying the natural environment and attempts to address global warming are almost inevitably bound to fail. Temperatures will continue to rise and social and political conflicts will intensify. The tragic truth is: we are selling our future for the next quarterly figures, the upcoming election results, and today s pleasure. Any realistic climate policy needs to focus on preparing societies for the consequences of escalating climate change and aim at strengthening social resilience to cope with the increasingly unstable natural world. Civil society is the only source of pressure that could build the necessary strength and support for climate protection.How We Sold Our Future is a crucial intervention into the most pressing issue of our time.

1

Knowledge without change

Imagine Glacier Bay National Park in the south of Alaska, a spectacular landscape dominated by huge glaciers, with massive slabs of ice crashing into the Arctic Ocean. In 2022, Alaskan author Tom Kizzia watched this spectacle of glacial calving from a cruise ship.1 He observed that this was once a sublime way to experience the power and beauty of untouched nature; today, however, it is impossible not to see in the breaking ice the accelerating and uncontrolled destruction of nature. Every roll of ‘white thunder’ feels like another loss.

We are surrounded by disturbing images of disrupted natural processes and the devastation of nature – the foundation of human life. These images often show tremendous suffering: we see families in Pakistan paddling boats through flooded villages; desperate people on the roofs of their flooded houses in Germany’s Ahr Valley; or Californians standing aghast in front of the ruins of their burnt homes. None of these natural events can be causally attributed to climate change directly, but the significant rise in extreme weather events with disastrous consequences is indeed the result of human-induced global warming, caused by an increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The broader public has known that the destruction was coming for close to forty years; we have not stopped it.

Figure 1. Global air temperature over the past thousand years

Source: Based on IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, New York, 2021, p. 6, Figure SPM.1.

Quite the opposite. Over this time period, annual global carbon dioxide emissions have not decreased, they have almost doubled. In the past thirty years alone, as much carbon dioxide was emitted into the atmosphere as in the previous two hundred years combined.2 The result is a steep rise in the global average temperature, a development that climate researchers refer to as ‘the great acceleration’. To date, the temperature has risen by almost 1.2 degrees Celsius compared to the early nineteenth century (see Figure 1). On our current path, with greenhouse gas emissions continuing to surge worldwide, the global average temperature is expected to increase by a further 1.3 degrees Celsius over the next eighty years – assuming that current climate action pledges are actually honoured.3

Human changes to the biosphere are damaging – or eliminating altogether – parts of the ecological niche in which our cultures can survive in relatively stable conditions. Global warming is now inevitable, and it is unclear if societies can adapt to the dramatically changed foundations of life that will result.4 The increased incidence of floods, droughts, heatwaves, and wildfires, together with declining biodiversity and rising sea levels, has the potential to significantly destabilize our societies. We will be confronted with questions of social inequality as never before: inequality both between the global North and the particularly hard-hit global South and between affluent and poorer social groups. Climate refugees, water scarcity, famines, and – in rich countries, too – ever higher costs for protecting people against natural disasters will lead to new distributional conflicts and to the very real possibility of severe social disorder.

We by no means understand all the causal chains in the highly complex climate system, and must constantly refine and adapt our climate models to take account of new knowledge. Nonetheless, one thing is certain: we know where the journey is heading and how drastically living conditions on Earth will shift. In short, climate change is no longer just a research problem for the natural sciences. Nor is its solution simply a technical challenge. We have already developed many safe and effective technologies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We also know which policy choices, changes in economic activity, and behavioural shifts would make a difference. The greatest challenge, rather, is social and cultural. If we know what to do and how to do it, why don’t societies act? That is the central question of this book.

The answer requires understanding the key social, political, and economic processes that drive our societies. I will sketch my answer by looking above all at the growth and profit rationale behind our capitalist economic system, together with its distribution of power, and the problems of political legitimacy in democratic political systems. Questions of cultural identity and status competition between consumers must also take centre stage. I will try to establish that the dominant role of power and culture in determining the social effects of climate change and how we fight it requires attending to the insights of social science. Natural scientists make the basic problem crystal clear and engineers propose technical solutions, but social scientists are uniquely equipped to investigate the economic, political, and cultural obstacles preventing us from taking urgent action against an ever-growing threat.

How do the workings of a capitalist market economy, of a parliamentary democracy, and of an individualistic culture shape the way we interact with the natural environment?5 My thesis is simple: the power and incentive structures of capitalist modernity and its governance mechanisms are blocking a solution to climate change. They are responsible, of course, for much else too. Other fundamental social problems also come up against power structures that impede their solution: witness the persistent and scandalous forms of poverty and social inequality. But while we can always hope that poverty and social inequality will be lessened at some point in the future and that a fairer world will emerge, the temporal dimensions of climate change are different. The world is warming rapidly and the catastrophic consequences of postponing action are irreversible. As the Indian historian Dipesh Chakrabarty remarks, the problems of climate change ‘confront us with finite calendars of urgent action. Yet powerful nations of the world have sought to deal with the problem with an apparatus that was meant for actions on indefinite calendars.’6

The ‘finite calendar’ has not spurred resolute action for the simple reason that the problem does not change the prevailing power and incentive structures, or not sufficiently. The fact is that the short-term gains of avoiding the costs of climate action exceed the current benefits of future climate security. This is because the positive effects of costly climate protection measures would only kick in when we are old, or dead, ‘merely’ benefiting later generations. Some people may also think that they can personally avoid the consequences of climate change, that they are protected by their wealth or by geography, that only ‘others’ will be affected. At best, an idealistic interest in the wellbeing of future generations – probably manifested most strongly when we picture the future lives of our own children and grandchildren – creates incentives to align our behaviour to more distant time horizons.

Since companies, politicians, and private citizens typically align their decision-making with short-term opportunities, we can expect them to overlook or downplay the future negative impacts caused by ignoring environmental damage.7 The common good that is our natural environment remains an exploitable resource sold on the market for profit. Its sale leads to its destruction. This is what I mean when I say that we have ‘sold’ our future.8

Time and again, in political discussions on climate change, we hear statements such as, ‘All we have to do is X’, or, ‘Why don’t we finally agree on Y?’ ‘X’ here might be the expansion of wind power, ‘Y’ setting limits on the use of natural resources or increasing the price of petrol and meat. However, the crucial question is: who is ‘we’? Change requires actors who are willing to act and who command the resources necessary to implement changes in a contested field populated by a multitude of other actors with very different interests and goals. Every political action takes place within a dense thicket of rules, practices, and institutions, but also of values and habits. These bind actors to structures and opportunities that set specific incentives and define the scope for action, thereby shaping decisions. This brings us to the workings of capitalist modernity, which is the social system that has determined how we interact with the natural foundations of life for the past five hundred years. It also shapes our current responses to climate change, as I will show in the following chapters.

That our responses are far from adequate to deal with the problem is demonstrated by the uninterrupted rise in global warming (see Figure 1). But what would a commensurate response look like? Implementing climate neutrality immediately? Three degrees of warming by the end of the century? And ‘commensurate’ in whose eyes? An economic cost–benefit calculation would not help here, because the assumptions involved are far too arbitrary.9 Rather, something like a norm is needed, and in fact such a thing does exist: most countries in the world have committed...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Ray Cunningham |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | Beckert • Capitalism • climate change • Ecological Crisis • ecological issues • Economic Sociology • Environment • Environmental economics • Environmental Ethics • Environmental Issues • Environmental politics • Environmental Sociology • Environmental Studies • how we sold our future • how we sold our future the failure to fight climate change • Jens Beckert • Organizational Sociology • Political Economy • Political Ethics • Social economics • social issues • the failure to fight climate change |

| ISBN-13 | 9781509565108 / 9781509565108 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich