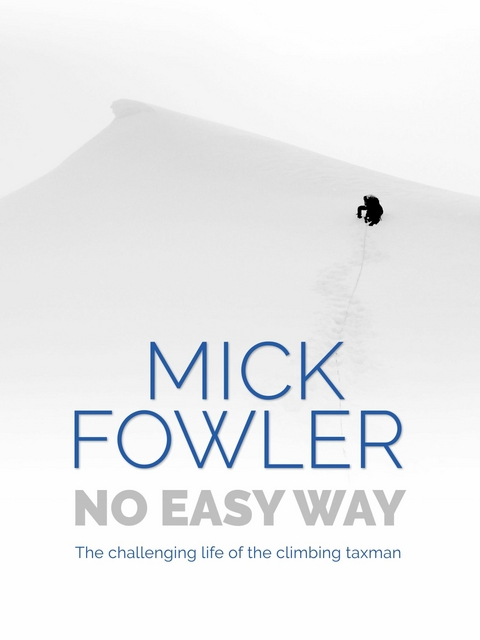

No Easy Way (eBook)

256 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-911342-91-5 (ISBN)

Mick Fowler was introduced to climbing in the French and Swiss Alps when he was thirteen by his father and soon developed an unstoppable enthusiasm for the sport. Every weekend through the winter climbing season he would make the long drive from London to tackle new winter routes in the Scottish Highlands, always managing to be back behind his desk in the tax office on Monday morning. His dedication paid off. Fowler became one the UK's foremost mountaineers, putting up new routes in most fields of climbing, with first ascents of gritstone E5s, remote sea stacks and the frozen drainpipes of London St Pancras to his name. Along the way, he helped to develop a whole new style of climbing on the chalk cliffs of Dover. But it is for mountaineering that Fowler is best known. A former president of the Alpine Club, he has made challenging climbs across the globe, earning him three prestigious Piolets d'Or - the Oscars of the mountaineering world - and the title of 'Mountaineer's Mountaineer' in a poll in The Observer. Remarkably, his climbing has taken place alongside a full-time job at the tax office, squeezing major mountaineering objectives into his holidays and earning him another title - 'Britain's hardest-climbing tax collector'. He retired from life as a taxman in 2017 but his enthusiasm for exploratory climbing remains undimmed.

I have a bulging file at home where I keep bits of information that might lead me to ‘interesting’ objectives for the future. Every year I pore over the accumulated possibilities and choose the most urge-inducing objective based on a list of points that must be satisfied for the truly perfect mountaineering trip.

The ideal objective should:

* have a striking line leading directly to the summit,

* be unclimbed,

* be visible from afar,

* be technically challenging,

* be objectively safe,

* be on an eye-catching mountain,

* be in a remote, ethnically interesting area,

* be somewhere I haven’t been before,

* have an aesthetically pleasing – and different – descent route.

It was 2003, the year after that memorable tax office appraisal, and my list had brought me to Sichuan province in China, to the town of Chengdu where I was lying face down in a massage parlour grimacing at the floor through a hole in the bed. The bony undulations of the Fowler body had initially made it difficult for the masseur to get a seal, but now he was making progress he was clearly keen to maintain the impetus. The suction pump was operated with great enthusiasm and the pain was becoming excruciating. I glanced sideways at the bed next to me where Neil McAdie was also face down. He too had opted for ‘cupping’ and his back sported eight 15-centimetre-diameter transparent suction pads through which I could see his skin sucked up to form tight fleshy lumps which stood proud like enormous inflamed sores. Perhaps testing the pain threshold was what Sichuan full-body massages were all about? Either way, it seemed unmanly to whimper and so I suffered in silence.

As usual we were a team of four, climbing as two pairs. My partner, Andy Cave, was an established all-rounder whose company I had enjoyed on trips to India and Yukon. Originally from a tight-knit mining community he had started his working life down the delightfully named Grimethorpe pit in Yorkshire and had used the free time afforded by the miners’ strike of 1984–1985 to discover the joys of rock climbing and the outdoors. From there he shocked his family by breaking generational links with the pit and went on to become a top-flight climber, climbing guide, part-time lecturer in mining dialects and motivational speaker. His rise from the claustrophobic pit to clear mountain air is brilliantly written up in his award-winning book Learning to Breathe.

Neil McAdie and Simon Nadin were not so well known to me but were good friends of Andy’s. Neil, on the bed next to me, worked in the outdoor retail trade while Simon was in the roped access industry and was the first ever winner of the world indoor sport-climbing championships.

The fact that we had all availed ourselves of a Sichuan full-body massage was Andy’s fault. He had been insistent that the British Mount Grosvenor expedition would benefit from this special treatment. But Andy and Simon had taken the only places in the massage parlour that boasted ‘fully qualified’ masseurs, leaving Neil and me to visit the seedier-looking and less frequented establishment next door.

Afterwards we compared our experiences. There was no doubt about it: ‘cupping’ in the unqualified establishment left a deeper impact. Neil and I sported large blood blisters on our lower backs, whereas Andy and Simon were relatively unscathed. Carrying a rucksack would have been excruciating and, much as I am a firm believer in trying (almost) everything once, unqualified Sichuan massages are perhaps best left until the climbing and trekking is over. Even then, be prepared to explain the curious lingering marks to loved ones back home …

But we had not come to China to sample the Chengdu massage parlours. Our objective had been to make the first ascent of Mount Grosvenor, an unclimbed 6,376-metre peak in the Daxue Shan range, which appeared to tick every box on my list. The highest peak in the range is Minya Konka, the most easterly 7,000-metre peak in the world. Although the climbing history of Minya Konka is well documented, we could find remarkably little information about the surrounding mountains. Our best photograph was a black and white shot from Die Großen Kalten Berge von Szetschuan, a 1970s German book by Eduard Imhof. It showed a spectacular peak with a steep and shady north-west face sporting a series of rock ribs separated by icy couloirs. The thirty-year-old photograph looked very exciting, and so the four of us had come to Sichuan to see what it was all about.

‘What do you think is going on?’

Neil’s question was a good one. We had been stationary at the side of the road for over two hours and absolutely nothing of note had happened. Four buses to Kangding had left Chengdu that morning at half-hourly intervals and, being keen, we had caught the first one. Now the following three were readily visible in the enormous snaking queue that had formed behind us.

‘The road is closed until 5 p.m.,’ announced an authoritative Irish lady – the only Westerner we were to see between Chengdu and base camp.

And it was. There were eight or so hours to waste. Simon, a keen photographer, passed the time poking his lens into every interesting scene he could spot. Andy did his best to learn an ethnic dice game and Neil and I just sort of mooched about, spending much of the time bouncing dangerously on a flimsy, wooden-slatted footbridge.

The Chinese just kind of accepted it without looking bored at all. Most of them, certainly the bus drivers, must have known that roadworks meant that the road was always closed until 5 p.m., so why they had joined the queue at 9.30 a.m. was difficult to understand.

‘The bus company haven’t been told to change their timetable,’ explained our interpreter, Lion, helpfully.

Five o’clock came and, sure enough, the queue started to move. Lion gathered a bit more information from officials and it transpired that traffic was allowed one way on alternate days. We were lucky that this happened to be a Chengdu to Kangding day. If it hadn’t been, our eight-hour wait would have been twenty-four hours longer.

The roadworks were truly amazing. This was steep mountain country, a world apart from the flatlands of the Sichuan basin and populated by endless hairpins and murky grey rivers thrashing their way through steepsided valleys. The road building was a 150-kilometre eye-opening mix of basic labouring and high-tech machinery. Thousands of ant-like labourers were living under plastic sheets at the side of the road and moving rocks into place by way of buckets on either end of a wooden pole over their shoulders. Conversely, at one point a gorge had to be crossed and seriously expensive equipment was much in evidence. The obvious availability of almost unlimited cheap labour and high-tech machinery seemed to say a lot about the rapid improvement of transport systems in the more remote parts of China.

Deep into the evening our bus was still bouncing painfully over the amazingly uneven surface. Eventually we came to a gasping halt at Kangding bus station, where a doctor in a white gown sprayed disinfectant in our direction. As Sod’s law would have it we had chosen to visit at the time of a serious outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Between November 2002 and July 2003, 774 people had died – the majority in south China – and here in Kangding there was a palpable feeling of concern, with a large number of people wearing face masks. As we stood there being sprayed it felt as if the great unwashed were arriving.

Lion – we never did discover his proper name – had been a very useful interpreter the year before when I had visited the Siguniang area of Sichuan. But that was his home territory where he had been dealing with locals that he knew and trusted. Here, where he had no contacts, he appeared continually concerned and was close to being a hindrance.

‘Don’t use these horsemen,’ he advised. ‘They are not trustworthy.’

This was all very good but in the (very) sleepy hamlet of Laoyulin, half an hour’s taxi ride from Kangding, there was not exactly a lot of choice. Lion was devoid of alternative suggestions. Negotiations over the price were interspersed with him regularly pointing out how shifty the men looked, how he could see it in their eyes, how their attitude made him nervous, how they kept changing the price. On and on it went. It was as difficult to keep our negotiator negotiating as it was to secure a sensible deal. But eventually hands were shaken, six horses were rustled up, and we were on our way. Within a hundred metres the loads had fallen from one horse.

‘You see – they are unreliable,’ announced Lion smugly.

Several load adjustments and perhaps two miles later we left the road and headed up the valley, which we guessed would lead us to Mount Grosvenor. I say ‘guessed’ because the trouble with exploratory trips in the pre-Google Earth era was that you were never quite sure. The sketch maps we had managed to get...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.10.2018 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Schlagworte | alpine climbing • Alpine Club • climbing biography • climbing books • extreme sports mountaineering • first ascent • greater range climb • Himalaya • rock climb • Scottish Highlands • UK climb |

| ISBN-10 | 1-911342-91-6 / 1911342916 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-911342-91-5 / 9781911342915 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich