1

An Overture of Sustainable Surface Water Management

Colin A. Booth and Susanne M. Charlesworth

1.1 Introduction

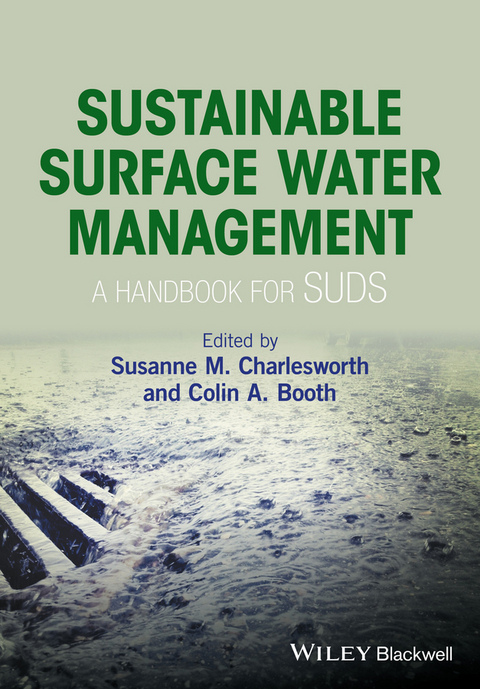

With more than 80% of the global population living on land that is prone to flooding, the devastation and disruption that flooding can cause will undoubtedly worsen with climate change (Lamond et al., 2011). The built environment has become more susceptible to flooding because urbanisation has meant that landscapes, which were once porous and allowed surface water to infiltrate, have been stripped of vegetation and soil and have been covered with impermeable roads, pavements and buildings, as shown in Figure 1.1 (Booth and Charlesworth, 2014).

Figure 1.1 An example of a flooded car park where the impermeable asphalt surface is retaining stormwater runoff.

Surface water policy, to address flooding‐related issues, differs widely across various regions and countries. For instance, in the UK, which is made up of four individual countries (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), Scotland has policies that have enabled sustainable drainage to be implemented as a surface water management strategy for about the past 20 years; whereas, England, Wales and Northern Ireland have yet to completely embrace sustainable drainage devices in their planning policies and guidance, and hence it is not yet widely implemented (Charlesworth, 2010).

1.2 Surface Water Management

The Victorians (1837–1901 in Britain) undoubtedly made remarkable strides towards innovative approaches to the water resource challenges of their day. Facing the dual contests of addressing rapid population expansion and industrial urbanisation, a need developed for high capacity systems to deal with societal water supply and treatment. Comparable approaches were exported or developed independently across the globe, as other nations faced similar challenges. In the UK, by a combination of philanthropy, public subscription and corporate vision, the infrastructure that would provide the vastly increased urban areas with sufficient clean water and the ability to discharge the surplus was put in place; and with it came the notion of the management of water as a single problem with one overarching solution: the provision of drains. However, while the solutions created by the Victorian engineers were magnificent in their day, the legacy of putting water underground seems to have created a collective mental block for many (Watkins and Charlesworth, 2014).

Nowadays, as mentioned earlier, urbanisation has had a transforming effect on the water cycle, whereby hard infrastructure (e.g. buildings, paving, roads) has effectively sealed the urbanised area (Davies and Charlesworth, 2014). As a consequence, excessive surface water runoff now exacerbates river water levels and overloads the capacity of traditional underground ‘piped’ drainage systems; this in turn contributes to unnecessary pluvial flooding. To many people, the solution is simply to replace the existing pipes with higher capacity ones. However, as Water UK (2008) states, bigger pipes are not the solution for bigger storms. Therefore, society should be encouraged to look towards more sustainable solutions.

1.3 Sustainable Surface Water Management

‘Sustainable drainage’ means managing rainwater (including snow and other precipitation) with the aim of: (a) reducing damage from flooding; (b) improving water quality; (c) protecting and improving the environment; (d) protecting health and safety; and (e) ensuring the stability and durability of drainage systems (Flood and Water Management Act, 2010).

Based on an understanding of the movement of water in the natural environment, sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) can be designed to restore or mimic natural infiltration patterns, so that they can reduce the risk of urban flooding by decreasing runoff volumes and attenuating peak flows. The choice of phrase or term that is applied to describe the approaches used can vary between countries, contexts and time. In the UK, for instance, SuDS is the most widely used term; whereas elsewhere in the world other relevant terms include surface water management measures (SWMMs), green infrastructure, green building design, stormwater control measures (SCMs), best management practices (BMPs), low impact development (LID) and water sensitive urban design (WSUD) (Lamond et al., 2015). However, whichever term is used, the benefits and challenges are similar (Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

Table 1.1 Examples of the benefits offered by sustainable drainage systems.

Source: List of benefits derived from CIRIA (2001).

| Sustainability | SuDS can provide an important contribution to sustainable development. |

| SuDS are more efficient than conventional drainage systems. |

| SuDS help to control and identify flooding and pollution at source. |

| SuDS help to promote subsidiarity. |

| SuDS can help to minimise the environmental footprint of a development. |

| SuDS are a clear demonstration of commitment to the environment. |

| Water quantity | SuDS can help to reduce flood risk by reducing and slowing runoff from a catchment. |

| SuDS can help to maintain groundwater levels and help to prevent low river flows in summer. |

| SuDS help to reduce erosion and pollution, as well as attenuating flow rates and temperature by increasing the amount of interflow. |

| SuDS can reduce the need to upgrade sewer systems to meet the demands of new developments. |

| SuDS can help to reduce the use of potable water by harvesting rainwater for some domestic uses. |

| Water quality | SuDS can reduce pollution in rivers and lakes by reducing the amount of contaminants carried by runoff. |

| SuDS can help to reduce the amount of wastewater produced by urban areas. |

| SuDS can reduce erosion and thus decrease the amount of suspended solids in river water. |

| SuDS can help to improve water quality by reducing the incidence of misconnection to foul sewers. |

| SuDS can help to reduce the need to use chemicals to maintain paved surfaces. |

| SuDS can prevent pollution by reducing overflows from sewers. |

| Natural environment | SuDS can help to restore the natural complexity of a drainage system and as a result promote ecological diversity. |

| SuDS help to maintain urban trees. |

| SuDS help to conserve and promote biodiversity. |

| SuDS can provide valuable habitats and amenity features. |

| SuDS help to conserve river ecology. |

| SuDS help to maintain natural river morphology. |

| SuDS help to maintain natural resources. |

| Built environment | SuDS can greatly improve the visual appearance and amenity value of a development. |

| SuDS help to maintain consistent soil moisture levels. |

| Cost reductions | SuDS can save money in drainage system construction. |

| SuDS can save money in the longer term. |

| SuDS can allow property owners to save money through differential charging. |

| SuDS can help to save money by reducing the need to negotiate wayleaves and easements. |

| SuDS can save money through the use of simpler building techniques. |

Table 1.2 Examples of the challenges posed by sustainable drainage systems.

Source: List of challenges derived from CIRIA (2001).

| Operational issues | There is no consensus on who benefits from SuDS. |

| There is a belief that SuDS may present maintenance challenges. |

| There may be concerns that the colonisation of SuDS may be too successful. |

| SuDS may present a target for vandals. |

| Design and standards | SuDS are not promoted by the Building Regulations. |

| There are no standards for the construction of SuDS. |

| SuDS require input from too many specialists. |

| SuDS may be seen as untried technology. |

| The guidance on how to build SuDS is limited or unclear. |

| It is difficult to predict the runoff from a site. |

| SuDS can be difficult to retrofit to an existing... |