Introduction

Abstract

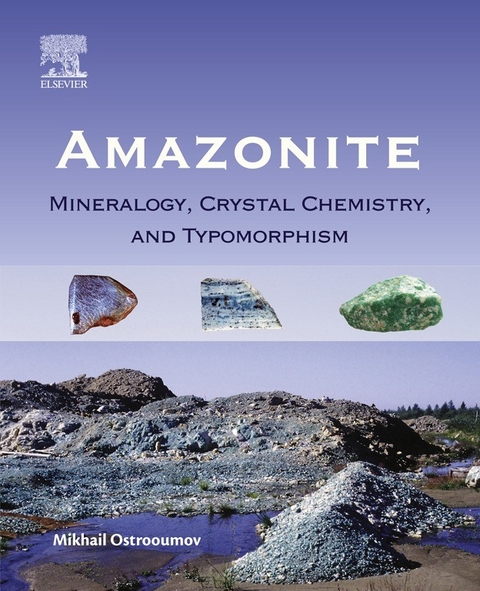

Amazonite (amazonstone) is a mineral that has attracted the attention of mineralogists for generations. Among the scientists that have investigated amazonite are many prominent geologists and mineralogists, including A. des Cloiseaux, Nikolay Kokcharov, Vladimir Vernadsky, Victor Goldschmidt, and Aleksandr Fersman. It is curious that half a century ago, amazonite was considered a very rare mineralogical variety of the potassium feldspar species. According to recent data, amazonite has been found on every continent except Antarctica. For over 200 years, the rich blue-green colors of amazonite have been the object of investigation by mineralogists and geologists. During the last few decades, geologists and mineralogists have discussed the use of amazonite in exploration for deposits of rare metals and rare-earth elements, and there are differing opinions regarding this problem.

Keywords

Amazonitic K-feldspar; Research history.

Amazonite is a mineral that has attracted scientific attention for generations and has been studied by prominent geologists including A. des Cloiseaux, N.I. Koksharov, V.I. Vernadsky, A.E. Fersman, V.M. Goldschmidt, and A.N. Zavaritsky. The history of amazonite discovery and scientific research is rich in riddles, paradoxes, misconceptions, and presuppositions. The time and place of the first amazonite finding is heavily debated even today. The very name of the mineral seems paradoxical, as there have been no known amazonite fields in the Amazon River basin. Evaluations of the mineral’s significance remain quite controversial

[1,

2,

23]. Despite more than two centuries of research history and innumerable papers dedicated to amazonite, it continues to draw the attention of geologists and mineralogists. What are the reasons for this continuing interest in amazonite?

The most noticeable aspect for any geologist encountering amazonite in the field or in the lab is certainly the mineral’s color: a rich palette of blue and green, characteristic of such rare and precious gems as turquoise, malachite, emerald, and aquamarine. However, this beautiful mineral with a color unique for a semiprecious stone has attracted the attention of a wide range of specialists mainly thanks to the discovery that it is not as rare as had been supposed previously. Amazonite is a variety of potassium feldspar, a group of minerals extremely widespread in the Earth’s crust. But it is due to its color that amazonite stands out among other potassium feldspars.

Scientists have undertaken numerous attempts to understand and decipher the nature of this mineral’s color. A wide variety of opinions have successively replaced one another as new characteristics of amazonite composition, crystal chemistry, and properties were discovered. In the last decades, the tendency has been to connect the chemical and structural characteristics of amazonite, and yet there is no hypothesis that would account for the diversity of its properties and crystal chemistry.

Until recently, amazonite was considered a mineralogical rarity not worthy of special attention and usable only as a semiprecious stone. The few amazonite fields known at that time were linked to certain types of Precambrian and Paleozoic granitic pegmatites. These pegmatites were noted by many researchers to have a particular composition of amazonitic paragenesis: amazonite associates with albite, topaz, beryl, fluorite, tourmaline, micas, and a wide range of rare-earth and rare-metal minerals. It is noteworthy that in the previous century, miners commonly considered amazonite a sure sign for finding topaz (known in Russian as a heavyweight): “Extensive experience taught miners to value this stone highly as the best sign for finding a ‘heavyweight’ (there are mines with amazonite but without topaz, but the reverse correlation had apparently never been observed). They know very well that the more intense the amazonite color, the greater the chance to hit a lucky vein”

[24]. Thus A.E. Fersman formulated this idiosyncratic prospecting rule that could be considered one of the first mineralogical criteria for pegmatite prospecting and evaluation. The formulation of this rule resulted in the contradictory situation that remains unsolved up to the present day: some researchers are very optimistic regarding the significance of amazonite as a search indicator of a certain mineral complex, while others remain skeptical of this potential use of amazonite. The negative conclusions were based mainly on occurrences of pegmatites similar in type to those containing amazonite, which display rich mineralization but no amazonite, as well as occurrences of amazonitic pegmatites with subeconomic or accessory mineralization.

A.N. Zavaritsky’s classic works on Ilmen Nature Reserve pegmatites contributed to the shifting of views on the narrowly mineralogical significance of amazonite color. The color was recognized by a range of geologists as an indicator of a certain metasomatic phenomenon causing a characteristic secondary color of microcline—the effect later named amazonitization after the suggestion of A.N. Zavaritsky.

The discovery of this phenomenon allowed a new, deeper approach to understanding the nature of amazonite color, including not only its cause (a presupposed presence of one or another isomorphic impurities in microcline), but also the time, modes, and conditions of its formation. Important observations made by A.N. Zavaritsky and other geologists connected amazonitic microcline color with albite and quartz development zones.

However, contradictory opinions still abound regarding the essence and meaning of the amazonitization process. Not all researchers accept even the mere possibility of secondary amazonitic color. The followers of A.E. Fersman, for instance, still consider crystallization of residual melt or fluid enriched with volatile components and rare elements as the only possible modes of amazonite formation. In relation to the potassium feldspars with amazonite color, the term K-feldsparing is used in addition to A.N. Zavaritsky’s term amazonitization. These cases have never been considered closely to determine the modes by which the color was formed, which could be either primary or secondary.

In addition, attempts have been made to substantiate the idea of de-amazonitization, that is, amazonite decoloration, as an alternative to amazonitization (secondary formed color). This has provided yet another possible explanation for the knotty pattern in the color of amazonite from certain deposits, but the question remained whether amazonite color is primary or secondary.

Discussions of this genetic problem might have remained a side issue of pegmatite genesis were it not for the mid-twentieth-century discoveries of large plutons of amazonitic granites and entire provinces of amazonite-bearing rock. It is worth noting that some of those areas were found to contain a minable concentration of a number of rare-metal minerals. Moreover, the conducted evaluations enabled some varieties of amazonitic granites to be classified as useful only for facing stone, and others as potentially promising raw material for the assemblage of lithophilous rare elements. As in pegmatite deposits, granite amazonitization to scale turned out to be commensurate with and closely linked to the processes of albitization, greisenization and ore formation. As a direct result, discussion has flared anew about the practical use of amazonite as a prospect indicator of certain mineral deposits and about the comparability of the petrological significance of amazonitization with that of other post-igneous processes. It is worth recalling here that some time ago an analogous discussion was taking place about the characteristics of granitoid albitization, which, as was discovered subsequently, occurs during the late post-igneous stages of granite intrusion formation. It has a variety of structural and morphological manifestations and varied ore-controlling significance.

At present, both the geochemistry and the distinctive features of amazonitization remain only partially clear. Multifaceted research of amazonite-bearing paragenesis would allow the description of the chemistry of all minerals contained therein. According to a range of research data, in comparison to associated potassium feldspars of common (non-amazonitic) color, amazonite displays higher concentrations of rubidium, cesium, plumbum, thallium, and certain other elements. However, despite the large number of papers treating the subject of the chemical composition of amazonite, the precise limits remain unknown as to the isomorphic capacity of this mineral in relation to rare and trace elements and their typical concentrations in amazonites contained in various genetic types of rocks. The aforementioned characteristics of amazonitic feldspar allow it to be classified as highly promising for determining the absolute age of the amazonite-bearing rock by means of three basic types of isotope analysis: potassium-argon, rubidium-strontium, and uranium-plumbum. The consistency of results must be checked against a wide range of identifiable ages.

The effusive analogues of Mesozoic amazonitic granites (so-called ongonites) as well as Alpine amazonitic pegmatites discovered in recent decades enable us to speak of a wide range of geological environments where amazonite can be found and highlight the necessity of discussing the typomorphic significance of this mineral.

The polemical character of the views on amazonite is the result of the wide variety of fragmentary and contradictory facts scattered...