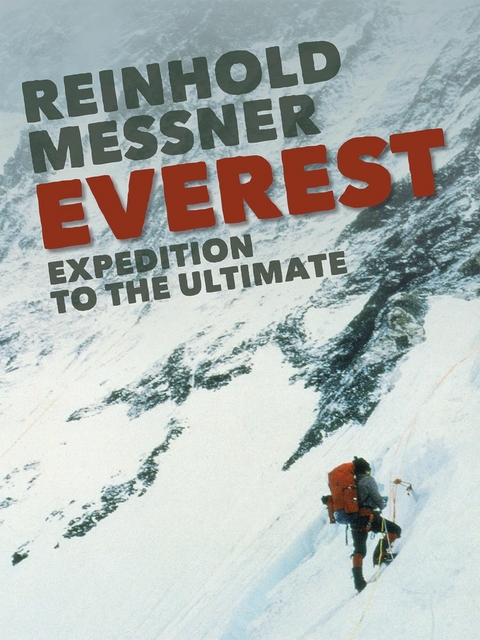

Everest (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-910240-21-2 (ISBN)

– Dawa Tensing’s Hat –

‘The snow was as deep as a man’s hips that year,’ says Dawa Tensing and stands up to give an idea of how they had had to break trail every day. Gesticulating with his hands, he bends the upper half of his body forward and takes a few steps as if he is pushing masses of snow away from his feet. His movements run down like clockwork. He knows what it means to climb at 8,000 metres without oxygen, to prepare a trail and to hump heavy loads. He has seen it all. He was there in 1924 when Norton attempted to climb Everest without oxygen.

At that time he had been one of the high-level porters. He was born sometime in the last century; he doesn’t know how old he is. Today he lives in the Solo Khumbu. Everest and Ama Dablam are visible over the gable of his house.

The ankle-deep spring snow hurts my eyes as I come down out of the two-storey mud house into Dawa Tensing’s small back yard. That is all he has left now. His fields in Khumjung, where he grew up, he has given to his children. He lives here close to the Thyangboche Monastery so that he can pray, look out at Everest and remember the old days. It hasn’t always been easy, his life, but it has been exciting. And as he stands talking before me with his hands, his feet and above all his twinkling eyes behind their narrow slits, the images tumble back. He has accompanied more than thirty expeditions and been several times to Everest. In 1953 he was there, under John Hunt, when the South Col route was first climbed. His face looks as if it has been chiselled from granite. He has a single tooth in his upper jaw which fits neatly into a gap in the lower. His white beard is sparse and his grey hair drawn into a knot. He wears colourful Sherpa dress, woven shoes, and as an extra – who knows from what expedition – a pair of ladies trousers.

A great number of letters and pictures are piled around his house, but they are unimportant to him. In his mind the expeditions have all merged together and he does not distinguish any particular year and any expedition leader. But he does remember individual instances and elaborates in minute detail – standing up and going step-by-step through his garden – what it is like to be at 8,000 metres or more. I could tell at once that this is a deeply-ingrained experience. He says we shall have to force ourselves to eat up there.

‘Yes, at altitude it is important to eat even if you don’t feel like it – and above all, to drink. But there’s no water and you mustn’t suck snow.’

Tsampa is what we should eat, he tells me, and for drink, tea – lots and lots of tea.

‘What was it like on the North side, the Tibetan side that time?’

‘Mallory and Irvine didn’t come back.’

‘Why, do you think?’

‘They kept climbing up in deep snow and didn’t come down again.’ Pause. ‘The wind will have got them, the wind.’

I want to know if he thinks they reached the summit or not. He shrugs his shoulders. To Dawa Tensing it is not so important whether they got up or not. They disappeared, that was the important thing.

‘It will have been the wind that got them,’ he repeats.

I ask him hesitantly what he thinks of our chances of climbing Everest without oxygen, whether indeed it is possible or not.

‘Yes, it must be possible. I have often been to the highest camps without it, and I have spent weeks on the South Col. All the other Sherpas and Sahibs were in bad shape after a few days up there, they were sick – couldn’t go any further – came down very shaky.’

The big prayer wheel in his smoky living room is turned by his wife, his third wife. He lost his first in 1956 while he was away on Everest. His eldest son was at that time with another expedition, and his wife heard that both the son and her husband had been caught under an avalanche. Accurate reports were few and far between in those days. She was distraught, went to the river and threw herself into the raging glacier water. When Dawa Tensing came home, he found an empty house. His son had indeed died in an avalanche, and his wife in the river. He married again, but lost his second wife also.

Dawa Tensing is no lamaist, but he prays a lot and reads Tibetan texts.

We will look in on him again when we come back. He would like to have details of an Everest climb, as he had always wished it.

Dawa Tensing presents me with his hat, an old Gurkha hat. I shall take it with me, at least into the great basin of the Western Cwm. On my return I shall bring it back to him.

‘I’ll need it again in the summer,’ he says, ‘against the rain and sun.’

Above the twisted shingles of his roof, a cloud is visible over the summit of Everest. A slender, black pyramid, it rises some 300 metres above the Nuptse-Lhotse Wall. It is unmistakably the highest peak in the whole region. Dawa Tensing turns away as I make to offer him a few rupees as a deposit for the hat. He won’t take any money. He wishes me luck and will see me again in the summer. I stand there in the little garden on the damp ground and watch the banner of cloud on the summit of Everest. Dawa Tensing has been close to this summit more than ten times, having approached both from the north and the south. He too gazes up, he has no regrets that he hasn’t been to the top. Expedition politics, he says, require a Sirdar like him, as the Sherpa leader, to spend much of the time in Base Camp supervising reinforcements and ensuring that each Sherpa is doing his job.[1]

As I go past the woodpile heaped in front of his house and shake his hand for the last time, Dawa Tensing says nothing. Then as I turn back to wave, he says, ‘Take much care. Eat plenty.’ He is reminding me how important it is to force yourself to eat when you are suffering the effects of altitude.

‘Come back,’ he calls, ‘and we’ll have a Chang party in my house. Come back!’

21 March. The huge prayer wheel turns regularly. A wisp of smoke hangs over the roof. Some snow still clings to the north-east eaves, the other side is dry. The little bleached prayer flags flutter in the wind, pointing the way to Everest.

The snow is melting in the midday warmth and water runs in rivulets along the well-trodden paths. Yak caravans plod through the sludge, bringing food to the high villages and farms and necessary bits of equipment for expeditions. Lost in thought, I wander alone beside the long prayer wall towards the mountains. It is too early for any downy green seeds on the high meadows, and the rhododendron bushes on either side of the track stand starkly, as if burnt, their leaves hanging brown and dusty. But the earth smells of spring.

As I turn Dawa Tensing’s hat thoughtfully in my hands, a feeling of calm washes over me. I have been so preoccupied with the prospect of Everest, in my dreams and throughout the journey, that I now no longer know who I truly am – am I this Sherpa who has learned to know Everest from all sides, or am I some crazy European who returns again and again in a desperate effort to find some deeper purpose to his life. With what enthusiasm and what calm acceptance Dawa Tensing had recalled his expeditions! They belong as much to his life as his three wives, or his house here amongst the mountain giants, or the abundant spring snow.

We have now been on the road for a week. We are going slowly in order to acclimatise, making short excursions into the surrounding villages, meeting the Sherpas who have to scratch a living in these barren high valleys south-west of Everest.

I have made up my mind to climb Everest, in much the same way as someone might decide to write a book or stitch a garment. And I am prepared for anything I might have to face on my way to the summit.

It is midday; the main expedition party is well ahead. By now the kitchen has probably been set up, so I will have to forego my meal. But it doesn’t matter. I still feel the glow of the golden-green Chang I enjoyed with Dawa Tensing, and although I am still a bit giddy, it has certainly done me no harm.

‘As far as Base Camp,’ Dawa had said, ‘you can drink chang. Chang – rakshi – whatever you like, but after that – no more – no alcohol at all. And no smoking either. That is important.’

He repeated this often as if he wanted to print it indelibly in my mind.

As I now scramble down into the churned-up stream bed of the Dudh Kosi, Ama Dablam stands behind me. There are mountains about which, because of their very appearance, no-one asks why we want to climb them. Their colour and their form are so striking and so attractive that the question would seem naive. Every mountain-lover would like to climb Ama Dablam. Every child would understand the challenge of such a mountain, soaring as it does, vertically upwards, its every line marrying together harmoniously on the summit. Why do we climb these mountains? Who can say? Indeed, I don’t think I would really want to know the reason, but I often indulge the theory that perhaps it has something to do after all with the fact that we men cannot bear children. Back at home, there always seemed to be a possibility that something, or someone – a desirable woman perhaps – might dissuade me from my intention to climb Everest. Here, the very idea seems strange; here Mount Everest is an intrinsic part of my life; I need no other partner.

Out of the corner of my eye I can see the fringe of prayer flags that I have wound around my hat; at the same time my feet come alternately into view ahead. It is as if they don’t belong to me as they trudge up through the oozy mud and pick their way steadily through the stones of the steep slope up to Pangboche. Now and then when I lift my head to peer out from under the brim...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.11.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-21-4 / 1910240214 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-21-2 / 9781910240212 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich