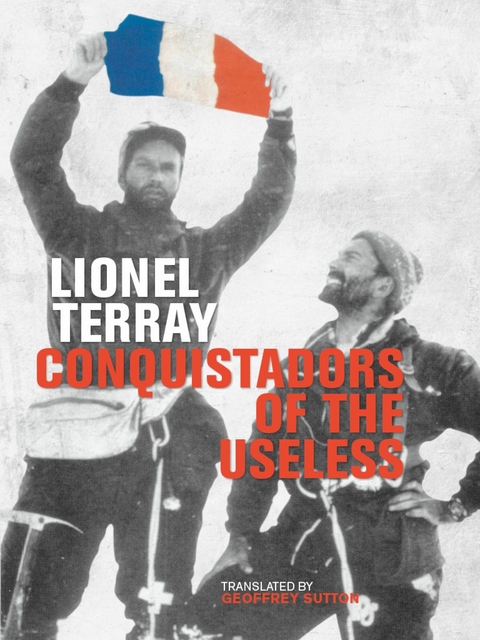

Conquistadors of the Useless (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-910240-17-5 (ISBN)

– Chapter Two –

First Conquests

The traditional military service had now been replaced by a kind of civilian service aimed at the virtues of manliness, industriousness, and public and team spirit, much extolled by the national leaders of the day. An institution called ‘Les Chantiers de la Jeunesse’ was set up to put young men of twenty-one through an eight months’ training. A similar but much smaller organisation called ‘Jeunesse et Montagne’, or J.M. for short, was formed on parallel lines. Only volunteers could serve in this corps d’elite, the idea of which was to inculcate qualities of service and leadership among youth by the practice of mountaineering, skiing and a rough life among the mountains generally. The J.M. was endowed with a body of instructors consisting of professional guides and skiing instructors plus a few amateurs who were admitted after a difficult entrance examination. The pay was poor, but the life, dedicated entirely to mountains, seemed fascinating.

I possessed all the necessary skills to pass these examinations without much trouble, and I realised that in this way I could find a method of supplying my material needs while pursuing my true ambitions. Since I was bound to get called up soon in any case for the ‘Service Civile’, I decided to anticipate matters by volunteering for the J.M. I went in at Beaufort around the beginning of May.

In all walks of life during wartime there was a certain degree of disorganisation, or rather improvisation, which lent to things an element of fantasy which we quite miss in these productive days. The J.M. was still in the early stages of its formation, and a general chaos reigned quite happily side by side with rigid military discipline. For some days after my arrival I spent my time, in company with some thirty other recruits, in planting potatoes. Then, by one of those mysterious dispensations which always seem to occur in organisations of this sort, despite the fact that a good third of the new personnel were farmers’ boys, I was designated to be a muleteer!

I had been quite used to cows from childhood, but had never come close to a mule in my life. Worse still, I entertained a wholesome terror for them, having heard that they were vicious, stubborn, and endowed with a most redoubtable capacity for kicking. When our group leader announced my new profession I asked him, my features tense with fear, just what I would be expected to do. He replied with the succinctness which characterises all great leaders of men:

‘Nothing to it. You go to the stable, you take the mules to drink at the trough, you give them one truss of hay per four mules, and you clean out the stable. That’s all for the moment.’

The only thing he forgot to tell me was that, owing to a short admin course, no one had appointed a new muleteer, and consequently the animals hadn’t eaten for two days. I went into the stable with all the innocence of the newly-converted going to his baptism, and if the animals seemed a trifle agitated I hardly noticed it.

‘It’s because they don’t know me yet’, I said to myself.

Dodging a kick vigorous enough to propel me into the next world, I squeezed in between two of the beasts in order to set them loose, then did the same for four others. Only then did it begin to dawn on me that I had done something rasher than climbing the Whymper couloir at four o’clock in the afternoon.[1] Wild with hunger and thirst, the mules stampeded in all directions, and one of them, baring his long yellow teeth, tried to bite me in the most uncivilised fashion. Only the agility which enabled me to climb like a flash into the hayrack saved me from being trampled to death. I would probably have been stuck there for hours if, finding the door open, the mules had not burst out into the village in an unbridled cavalcade. Fortunately I was speedily relieved of my duties as a muleteer, and sent off to be part of a team building new military quarters about five thousand feet up in the high pastures of Roseland.

The chalet in which we had to install ourselves was primitive in the extreme. Everything normally considered necessary to the maintenance of a group of men, even in the hardest sort of conditions, was lacking – camp-beds, mattresses, blankets, even a stove. All these things needed to be got up as quickly as possible, but, the season being very late that year, Roseland was still half buried in snow, and the last two or three miles of the road were unusable. The only method of transport was our own backs. The work of my own team consisted mainly of doing all this carrying. We had to do just one trip a day which, with a load of about a hundred pounds, took around three hours for the return journey. The hours were thus short, but the work required more than average energy, particularly inasmuch as, sleeping on the bare ground and eating inadequate food, simply to survive demanded a constant output. For this reason the team was made up of the stronger men. Used to working with mules, I was perfectly designed to replace them when the need arose!

The rough life we led at Roseland suited me ideally, except that three hours of work, however laborious, were not enough to appease my energies, so that I had to look around for other methods. With a few friends of similar tastes, I used to get up before dawn every day and climb the two thousand feet to the Grande Berge, a peak overlooking Roseland, on skis. After a swift downhill run came breakfast, then I would do a first carry, and in the afternoon another. Then the loads began to seem too light, so I started taking a little more each day. Some of the other porters joined in the game, which became a daily competition, until we were carrying up to a hundred and thirty odd pounds at a time.

It should be added that in those early days of the J.M. there reigned a wonderful team spirit and good humour. Our ideal may have been rather too simple, but most of us really did have an ideal for which we were willing to give our utmost strength. It was all very inspiring. In this atmosphere of shared high spirits and exhausting labour I passed days of intense and utter happiness. In the words of Schiller, ‘In giving of itself without reserve, unfettered power knows its own joy’.

Once the snow had melted, the life of our troop changed completely. Our time was divided between forestry, ski-mountaineering, physical culture and, in a milder sort of way, climbing. The professional guides and instructors played a purely technical role, and the disciplinary side was looked after by the various grades of ‘leaders’. These were mostly officers or non-commissioned officers from the disbanded air force. Most of them knew little about mountains and their lore, and some of them loathed the whole business. For this reason mountain activity was not always taken as far as it should have been, despite the enthusiasm of both the instructors and the volunteers.

The activity of each group depended a lot on the tastes of its leader, who might give priority according to his preferences to skiing, climbing, hill-walking, manual labour or cultural activities. By a stroke of luck our leader was an ex-N.C.O. of alpine troops, an experienced mountaineer, and a one-time ‘Bleausard’.[2] Thanks to him our time was mainly spent on long ski excursions along the high ridges of Beaufortin, or else in rock climbing. We worked out a number of practice grounds along the foot of the limestone pinnacles and crags above Roseland. At least twice a week we had to undergo half a day’s climbing. I had no trouble in outclassing most of the others on these occasions, but one, named Charles, sometimes outdid me. Tremendous competitions resulted when, our safety ensured by a rope from above, we would strive to surpass each other by means of the most spectacular rock-gymnastics.

It was now that I first met Gaston Rébuffat. He was attached to a troop quartered in the picturesque Arèche valley, with its dense pine forests and lush pastures dotted with old rustic chalets. There being no rocks to climb in that pastoral area, this troop was forced to come up to Roseland for the purpose. Caught by the rain one day, they took shelter in our chalet, and somebody told me that among them was a young fellow from Marseilles who claimed to have done some big climbs. I had often heard about the wonderful training ground formed by the ‘calanques’, the rocky coast near Marseilles, and I excitedly got myself introduced to the new phenomenon.

In those days Rébuffat was of rather startling appearance at first sight, tall, thin and stiff as the letter I. His narrow features were animated by two small, black, piercing eyes and his somewhat formal manners and learned turn of phrase contrasted comically with a noticeable Marseilles accent. All this took me a bit by surprise, but after a slightly strained beginning a mutual sympathy grew up quickly, and we spent the whole afternoon walking around in the rain talking climbing. As you would expect, each asked the other what he had done. I was astonished to learn that, without any other experience than the rock gymnastic technique learnt in the Calanques, Rébuffat had done high mountain routes equivalent to my ultimate ambitions. The conversation came round to our future projects next, and again, his seemed completely extravagant to me. His whole conception of mountaineering, normal enough today, was far in advance of its time and entirely novel as far as I was concerned.

Among all the climbers I had met up to that time mountaineering was a sort of religious art, with its own traditions, hierarchies and taboos, in which cold reason played quite a small part. Having grown up among the priesthood, I had blindly observed all the rites and accepted the articles of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.10.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-17-6 / 1910240176 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-17-5 / 9781910240175 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich