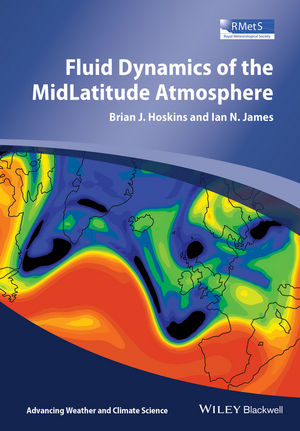

Clearly structured throughout, the first of three themes deals with the development of the basic equations for an atmosphere on a rotating, spherical planet and discusses scale analyses of these equations. The second theme explores the importance of rotation and introduces vorticity and potential vorticity, as well as turbulence. In the third theme, the concepts developed in the first two themes are used to give an understanding of balanced motion in real atmospheric phenomena. It starts with quasi-geostrophic theory and moves on to linear and nonlinear theories for mid-latitude weather systems and their fronts. The potential vorticity perspective on weather systems is highlighted with a discussion of the Rossby wave propagation and potential vorticity mixing covered in the final chapter.

Having gained mathematics degrees from Cambridge and spent some post-doc years in the USA, Brian Hoskins has been at the University of Reading for more than 40 years, being made a professor in 1981, and also more recently has led a climate institute at Imperial College London. His international activities have included being President of IAMAS and Vice-Chair of the JSC for WCRP. He is a member of the science academies of the UK, Europe, USA and China, he has received the top awards of both the Royal and American Meteorological Societies, the Vilhelm Bjerknes medal of the EGU and the Buys Ballot Medal, and he was knighted in 2007.

From a background in physics and astronomy, Ian James worked in the geophysical fluid dynamics laboratory of the Meteorological Office before joining the University of Reading in 1979. During his 31 years in the Reading meteorology department, he has taught courses in dynamical meteorology and global atmospheric circulation. In 1998, he was awarded the Buchan Prize of the Royal Meteorological Society for his work on low frequency atmospheric variability. He has been President of the Dynamical Meteorology Commission of IAMAS, vice president of the Royal Meteorological Society, and currently edits the journal Atmospheric Science Letters. He now serves as an Anglican priest in Cumbria.

This book gives a coherent development of the current understanding of the fluid dynamics of the middle latitude atmosphere. It is primarily aimed at post-graduate and advanced undergraduate level students and does not assume any previous knowledge of fluid mechanics, meteorology or atmospheric science. The book will be an invaluable resource for any quantitative atmospheric scientist who wishes to increase their understanding of the subject. The importance of the rotation of the Earth and the stable stratification of its atmosphere, with their implications for the balance of larger-scale flows, is highlighted throughout.Clearly structured throughout, the first of three themes deals with the development of the basic equations for an atmosphere on a rotating, spherical planet and discusses scale analyses of these equations. The second theme explores the importance of rotation and introduces vorticity and potential vorticity, as well as turbulence. In the third theme, the concepts developed in the first two themes are used to give an understanding of balanced motion in real atmospheric phenomena. It starts with quasi-geostrophic theory and moves on to linear and nonlinear theories for mid-latitude weather systems and their fronts. The potential vorticity perspective on weather systems is highlighted with a discussion of the Rossby wave propagation and potential vorticity mixing covered in the final chapter.

Having gained mathematics degrees from Cambridge and spent some post-doc years in the USA, Brian Hoskins has been at the University of Reading for more than 40 years, being made a professor in 1981, and also more recently has led a climate institute at Imperial College London. His international activities have included being President of IAMAS and Vice-Chair of the JSC for WCRP. He is a member of the science academies of the UK, Europe, USA and China, he has received the top awards of both the Royal and American Meteorological Societies, the Vilhelm Bjerknes medal of the EGU and the Buys Ballot Medal, and he was knighted in 2007. From a background in physics and astronomy, Ian James worked in the geophysical fluid dynamics laboratory of the Meteorological Office before joining the University of Reading in 1979. During his 31 years in the Reading meteorology department, he has taught courses in dynamical meteorology and global atmospheric circulation. In 1998, he was awarded the Buchan Prize of the Royal Meteorological Society for his work on low frequency atmospheric variability. He has been President of the Dynamical Meteorology Commission of IAMAS, vice president of the Royal Meteorological Society, and currently edits the journal Atmospheric Science Letters. He now serves as an Anglican priest in Cumbria.

Preface

We have developed this book from lectures given by us and others in the Department of Meteorology at the University of Reading. Since 1965, this department has been an important centre for the study of meteorology and atmospheric science. Indeed, for many years, it was the only independent department of meteorology in the United Kingdom able to offer a full range of undergraduate and postgraduate teaching in meteorology. Many scientists and meteorologists have spent time at Reading either as students or researchers. So our book is a record of one facet of the teaching they met at Reading, and it aspires to encapsulate something of the spirit of the Reading department.

During the early part of the twentieth century, meteorology made the transition from a largely descriptive, qualitative science to a firmly quantitative science. At the heart of that transition was the recognition that the structure and development of weather systems were essentially problems in fluid dynamics. In the 1920s, the scientists of the Bergen School recognized this but lacked the mathematical tools to link their descriptive models of cyclone development in terms of air masses and fronts to the basic equations of fluid dynamics. In the 1940s, modern dynamical meteorology was born out of the recognition by Eady, Charney and others that cyclone development could be viewed as a problem in fluid dynamical instability.

Even so, great simplifications proved necessary to render the problem tractable. Amongst these simplifications was the linearization of the governing equations. The highly nonlinear equations governing fluid dynamics were reduced to relatively simple linear forms whose solutions can be written in terms of traditional analytic functions. Even so, these simplified equations could only be solved for very simple idealized circumstances. For example, the work of both Charney and Eady was confined to flows which varied linearly in the vertical but had no variation in other directions. There was still a big gap between theory and observation. The development of the digital computer in the 1950s opened up the possibility of bridging this gap. While their nonlinearity and complexity rendered the governing equations resistant to analytical solution, the digital computer could generate numerous particular solutions to discretized analogues to the governing equations. So two separate branches of dynamical meteorology developed. On one hand, the drive for weather forecasts and, increasingly, for climate modelling led to the development of elaborate numerical models of atmospheric flow. As computer power increased, these models became more realistic, with higher resolution and fewer approximations or simplifications to the governing equations, and with more elaborate representation of the processes driving atmospheric motion such as radiative transfer, cloud processes and friction. On the other hand, more sophisticated mathematical techniques drove the development of analytical theory either to better approximations to the governing equations or to explore more complex physical scenarios. As a result, there was a growing gulf between numerical modelling, theoretical meteorology and observation.

Our approach at Reading, both in terms of teaching and research, started with the intention of bridging this gulf. The word ‘model' had become somewhat limited in its use in meteorology: it tended to refer to the large and elaborate numerical weather prediction and global circulation models that were primary tools in many applications of meteorology. But the word has far wider meaning than that. A model is any abstraction of the real world, any representation in which certain complexities are eradicated or idealized. All of meteorology, indeed, all of science, deals in models. They may be very basic, starting with conceptual verbal or picture models such as the Norwegian frontal model of cyclone development. They may be exceedingly complex and include a plethora of different processes. The coupled atmosphere–ocean global circulation models now used to study climate change exemplify this sort of model. But between these extremes lie a hierarchy of models of differing degrees of complexity. These range from highly idealized analytic models, models with only very few degrees of freedom, through models of intermediate complexity, right up to fully elaborated numerical models. Good science involves the interaction between these different levels of model and with observations, finding out which elements of the observed world are captured or lost by the different levels of model complexity.

A very complex model may give a faithful representation of the observed atmosphere, but of itself it can lead to rather limited understanding. A very simple model is transparent in its working but generally gives but a crude imitation of a complex reality. Intermediate models, grounded in constant reference to observations and to other models in the hierarchy, can illuminate the transition from transparent simplicity to elaborate complexity.

Our book focuses on the simpler and intermediate complexity models in this hierarchy. Although we shall refer to the results of calculations using elaborate numerical models, we have not set out to describe such models. That is a major topic, bringing together dynamical meteorology and numerical analysis, and deserves a textbook of its own. However, we shall make use of results from numerical models in a number of places.

Our textbook is based upon various lecture courses that we have given to students, both postgraduate and advanced undergraduate, in the Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, over many years. Many of our postgraduate students came to Reading with a first degree in other quantitative disciplines, so our teaching assumed no prior acquaintance with fluid dynamics and the mathematical techniques used in that discipline. Neither did we assume any prior knowledge of meteorology or atmospheric science. We did assume basic knowledge of vector calculus and differential equations. However, in order to make this book self-contained, we have included an appendix which gives a brief introduction to the essential elements of vector calculus assumed in the main body of the text. So our intended readership is primarily postgraduate and advanced undergraduate students of meteorology. We hope others, particularly quantitative scientists who wish to become better acquainted with dynamical meteorology, will also find our book interesting.

Our text begins with an opening chapter which gives a broad brush survey of the structure of the atmosphere and the character of atmospheric flow, particularly in the midlatitude troposphere. This opening chapter introduces in a qualitative way a number of concepts which will be elaborated in subsequent chapters.

Then follows our first major theme: a basic introduction to classic fluid dynamics as applied to the Earth's atmosphere. After deriving the fundamental equations in Chapter 2, we introduce the various modifications that are needed for this application. Foremost among these are the roles that the rotation of the Earth and its spherical geometry, and the stable stratification of the atmosphere play. Perhaps the most important chapter in our first theme is Chapter 5, which develops the technique of scale analysis and applies it systematically to flows in the atmosphere. Our focus of interest is upon the synoptic scale weather systems of the midlatitudes, but the discussion points to how other situations might be approached.

Our second theme recognizes that atmospheric flow on the larger scales is dominated by rotation. The Earth rotates on its axis and individual fluid elements spin as they move around. Such spin is a primary property of the atmosphere or ocean, and our insight into atmospheric behaviour is developed by rewriting the equations in terms of spin or ‘vorticity'. Equations describing the processes which generate and modify vorticity result, and we spend some time exploring these equations in simple contexts. These simple examples help to develop a language and a set of conceptual principles to explore more elaborate and more realistic examples. A powerful unifying concept is a quantity called ‘potential vorticity', which is introduced in Chapter 10.

Our third theme makes up the remainder of our book. That theme is the dynamical understanding of middle latitude weather systems exploiting the near balance between certain terms in the governing equations. Such a balance links together dynamical, pressure and temperature fields and constrains their evolution. Maintaining a near-balanced state determines the response of the atmosphere to thermal and other forcing. With these concepts, we are able to discuss the evolution of weather systems as problems in fluid dynamical instability, and we are able to extend our discussion to more elaborate, nonlinear regimes. Frontal formation is revealed as an integral part of cyclone development, and at the same time, developing weather systems play a central part in determining the larger scale flow in which they are embedded. Through the concept of balance, potential vorticity is revealed as a primary concept in modern dynamical meteorology.

This book is intended as a readable textbook rather than a research monograph. We hope that the material is largely self-contained. Consequently, we have made no attempt to provide a comprehensive and exhaustive bibliography. Rather we have included some suggestions for further reading which will give the interested reader a starting point from which to explore the literature. Modern electronic databases and citation indices make such exploration much easier...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.8.2014 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Advancing Weather and Climate Science |

| Advancing Weather and Climate Science | Advancing Weather and Climate Science |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geologie |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Meteorologie / Klimatologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Angewandte Physik | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Atmosphere • Atmospheric • Atmospheric Physics & Chemistry • atmospheric sciences • Book • coherent • Current • Development • Dynamics • earth • earth sciences • Fluid • Geowissenschaften • importance • invaluable • Klimatologie u. Meteorologie • Knowledge • latitude • Level • Meteorologie • meteorology • Middle • Physik u. Chemie der Atmosphäre • Physik u. Chemie der Atmosphäre • previous • primarily • Quantitative • resource • Rotation • Scientist • Strömungsmechanik • Stratification • Strömungsmechanik |

| ISBN-13 | 9781118526040 / 9781118526040 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich