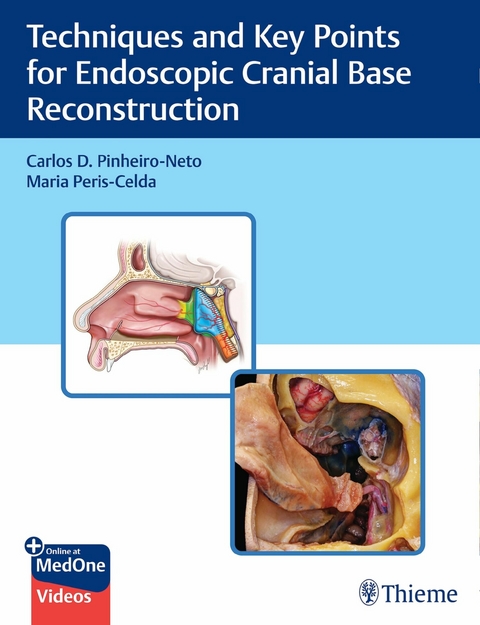

Techniques and Key Points for Endoscopic Cranial Base Reconstruction (eBook)

190 Seiten

Georg Thieme Verlag KG

9781638537014 (ISBN)

1 Principles of Endoscopic Cranial Base Reconstruction

Tyler Kenning, Laura Salgado-Lopez, Maria Peris-Celda, and Carlos D. Pinheiro-Neto

1.1 Introduction

-

Endonasal approaches to the cranial base have not only permitted access to an increasingly vast range of pathology but have also brought new surgical challenges.

-

Reconstruction after cranial base surgery separates the sinonasal and intracranial compartments, preventing postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistulas, and limiting the morbidity and mortality.

-

The goals for repair of the cranial base include the elimination of dead space, providing structural support, contour and function of the cranial base, and protection and preservation of intracranial and orbital contents.

-

Beyond the need for reoperation and further repair, reconstruction failures have the potential for significant morbidity: meningitis, subdural hemorrhage, intracranial abscess, hydrocephalus, pneumocephalus, and even death. 1 Delayed complications include epistaxis, chronic rhinosinusitis, and sinonasal mucocele formation. 2

-

Advances in cranial base repair may be the most critical factor allowing for the increasing use of endoscopic endonasal surgery of the cranial base.

1.2 Fundamentals of Endonasal Reconstruction

-

The principles of endonasal cranial base reconstruction remain similar to transcranial approaches.

-

Challenges for endonasal reconstruction include the lack of supporting structures and the effects of gravity.

-

Reconstruction in purely transsellar surgery can be accomplished with greater than 99% success rate with nonvascularized mucosal grafts alone. 3

-

Initially, dural and osseous defects were largely repaired with nonvascular tissue grafts in expanded endonasal approaches. Postoperative CSF leaks occurred in up to 15% of the cases. 4, 5

-

The utility of vascularized tissue for cranial base coverage becomes evident when extending beyond the sella (success rates over 95% in the anterior cranial base vs. 67–93% with nonvascularized grafts). 6

-

Resection of tumors with large mass effect in the frontal lobes creates a large surgical cavity intracranially which makes the endonasal reconstruction of the anterior cranial base more challenging. The absence of adequate support of the frontal lobes for the reconstruction and the column of CSF that forms between the brain and the reconstruction increases the risk of failure. Partial filling of the intracranial surgical cavity with absorbable sponges and/or fat graft, particularly along the anterior edge of the defect, may prevent intracranial displacement of the flap and CSF leak.

-

Defects in the posterior fossa with transclival approaches are the most problematic to repair. Nonvascularized tissues have proven ineffective with postoperative CSF leaks occurring in nearly 40% of the cases. Conversely, with flap repair and use of postoperative lumbar drain, the rates of CSF fistulas in these cases can be reduced to less than 5%. 5, 6, 7

-

Certain pathologies and comorbidities are associated with increased risk for postoperative CSF leaks, and more robust reconstructions should be considered for these patients. 8, 9, 10

-

Meningiomas—treatment involves osseous and dural resection, as well as disruption of the arachnoid.

-

Craniopharyngiomas—with potential extension through the basilar cisterns and into the ventricular system.

-

Cushing’s disease—compromised healing due to endocrinopathy, likely obesity with associated intracranial hypertension, possible obstructive sleep apnea requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

-

Morbid obesity—associated with intracranial hypertension.

-

Obstructive sleep apnea—requirement of CPAP postoperatively.

-

Idiopathic CSF leaks/encephaloceles/meningoencephaloceles—associated with obesity and increased intracranial pressure.

-

History of or need for radiotherapy—vascularized flaps are more likely to withstand long-term effects of radiotherapy.

-

Immunosuppression/steroid use/diabetes—compromised healing.

-

1.3 Repair Options

-

There is a wide variety of options available for endoscopic cranial base reconstruction, including free mucosal grafts, autologous fat, muscle, and fascia lata, allograft dural substitutes, and vascularized flaps.

-

Synthetic rigid materials (titanium meshes, porous polyethylene implants, etc.) should be avoided due to the higher risk of infections and/or extrusions. If a more rigid reconstruction is desired, vascularized composite flaps are recommended.

-

The selection of the repair option is based on the anatomic location and extent of the defect, the degree and type of intraoperative CSF leak, the underlying pathology, and patient comorbidities.

-

Any dural defect is usually repaired with an intradural graft, especially if there is an accompanying arachnoid opening. In cases where the arachnoid is exposed and contains the CSF flow, an onlay mucosal reconstruction may be enough to repair the defect.

-

Autologous vascularized flaps have the greatest success rates in preventing postoperative CSF leaks. However, their use is commonly accompanied by additional morbidity. When effective alternatives are available, “non-flap” repairs may be considered. 6

-

Absorbable sealants and glues are useful for holding multilayered repairs in position. These should be applied over top of the repair and then supported by nasal packing. If sealants/glues are placed between layers of the repair, a gap will develop with their absorption, preventing appropriate healing of the repair.

-

Dissolvable packs are preferred to limit patient discomfort with removal. When greater pressure is needed to the cranial base repair, nonabsorbable packing should be considered. 9

-

Improvements in reconstruction materials and techniques have allowed moving away from lumbar CSF drains in the majority of the cases.

-

An exception may be in posterior cranial fossa surgery/large transclival approaches where the postoperative use of lumbar drains has been shown to be a more effective adjunct to the direct repair. 11

-

Early surgical reexploration and repair revision is advocated instead of only lumbar drainage for treatment of postoperative CSF leaks.

-

If a postoperative CSF fistula is suspected, direct bedside nasal endoscopy is performed, and if a defect is evident or still unclear, proceed to evaluation in the operating room. 12 With attempts at lumbar drainage alone in this setting, the failure rate and associated morbidity (infection, overdrainage, subdural hematomas, tension pneumocephalus, etc.) are high.

1.4 Vascularized Reconstruction

-

The use of vascularized flaps revolutionized the field of endoscopic endonasal surgery and broadly widened its applicability.

-

The most commonly used flaps are summarized in ▶ Table 1.1 and ▶ Table 1.2 . Each of the different options will be detailed in latter chapters.

-

The perichondrial or periosteal surface of intranasal flaps must contact bone along its entire length. This contact is essential circumferentially not only around the cranial base defect but also along the proximal portion of the flap.

-

If the proximal portion of the flap does not contact bone or other nonmucosal surface, the contraction during the healing process intensifies, pulling the flap away from the defect and increasing the risk of CSF leak.

-

In order to maximize the length of the flap, all bone ridges and septations within the sinuses should be removed to optimize the bone contact of the flap. If excess bone is left, the folds of the flap along the septations will shorten its “usable” area and increase the risk of dead space underneath the flap. 13

-

When possible, intranasal flaps should have their donor...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.1.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Stuttgart |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Chirurgie ► Neurochirurgie |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► HNO-Heilkunde | |

| Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Innere Medizin ► Pneumologie | |

| Schlagworte | CSF Leak • Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery • free flap • inferior turbinate flap • nasoseptal flap • pericranial flap • skull base defect • temporalis muscle flap |

| ISBN-13 | 9781638537014 / 9781638537014 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich