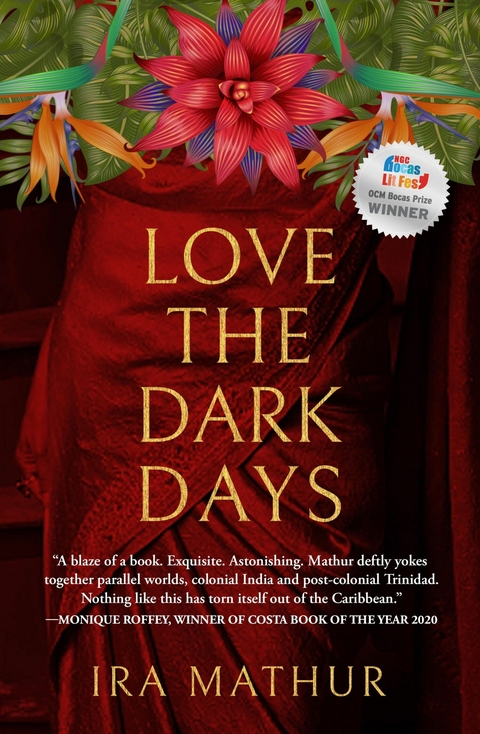

Love the Dark Days (eBook)

232 Seiten

Inpress Limited (Verlag)

978-1-84523-569-7 (ISBN)

Ira Mathur is an Indian-born journalist and broadcaster long resident in Trinidad. She has written over eight hundred columns on politics, economics, social, health and developmental issues, locally, regionally and internationally.

- A Guardian biography of the year 2022- Non-Fiction winner of the OCM Bocas Prize for Literature 2023This frank, fearless and multi-layered debut centres on a privileged but dysfunctional Indian family, with themes of empire, migration, race, and gender. The Victorian India elephant in the room in Ira Mathur's silk-swathed memoir, Love The Dark Days is in chains. By the time calypso replaces the Raj in post-colonial Trinidad, the chains are off three generations of daughters and mothers in a family in their New World exile. But they are still stuck in place and enduring insecurity and threats, seen and unseen. Set in India, England, Trinidad and a weekend in St Lucia, with Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, Love the Dark Days follows the story of a girl, Poppet, of mixed middle-class Hindu and Elite Muslim parentage from post- independent India to her family's migration to post-colonial Trinidad. Profoundly raw, unflinching, layered, but not without threads of humour and perceived absurdity, Love the Dark Days reassembles the story of a disintegrating Empire. "e;Reads like a fictional family saga as it leaps back and forth in time against a backdrop of patriarchal hegemony and a collapsing empire"e; - Guardian Best Biographies of 2022"e;Compelling"e; The Observer"e;A gem of a memoir... Monique Roffey is spot on when she calls it a blaze of a book"e; The Bookseller

Ira Mathur is an Indian-born journalist and broadcaster long resident in Trinidad. She has written over eight hundred columns on politics, economics, social, health and developmental issues, locally, regionally and internationally.

ONE

Kelly Village, Trinidad, 2000

I would like to see a kite in the blank blue sky. This rootless place of sameness is not where she, or we, thought she would end her days.

Mummy, Daddy, Winky, Angel and I have been standing under the shed watching Burrimummy’s grave being dug. She has been dead for less than twenty-four hours.

The noonday sun bounces off lumpy graves covered in thick weedy grass, off whitewashed houses on stilts, skims over the fields to the narrow river where it rests its egg-yolk reflection.

Burrimummy is inside an open wooden box on the concrete floor to our right, swaddled from head to foot like a mummy in two yards of white cotton. This is the two yards of white cotton she always talked about, carried about with her, repeatedly replaced. It is now being put to use.

Her creamy skin, of which she was so proud, is now a marmoreal jaundiced yellow, its dull shine reflecting the harsh light as if it were a crumbling bust in a museum.

The round-faced mortician with the red-hennaed beard informed us he had turned her head to the East the previous night, ‘before she get too stiff.’

It is so quiet I can hear the flapping of Angel’s white dupatta against her narrow shoulders.

Angel never thought Burrimummy would actually die. My first memory of Angel is of a chubby, pink-faced three-year-old, stumbling around in the many rooms of Rest House Road crying, saying that Burrimummy was ‘dying of a broken heart’. Burrimummy had then appeared and asked, ‘What would Angel do in this big house by herself?’ The two wept, unaware of anyone else.

Angel says ‘no’ decidedly when the mortician says this is our last chance to touch her face. She had already had her time doing that yesterday evening when she lay down on Burrimummy’s bed with her and stroked her still warm face for almost an hour until the white van came to take Burrimummy away. When the paperwork was finished and the body released from the nursing home, Angel wanted to climb in because, as she explained patiently to everyone who tried to prevent her, ‘Burrimummy will be alone. She needs me.’

We held Angel back while the van raced into the dark.

If I close my eyes, I reach back to the beginning when we were young and in her care in 17 Rest House Road.

Bangalore, India, 1976

It’s three in the afternoon; the end of the school day.

The nuns of the Sacred Heart Girls’ High School unlock the heavy padlock and pull open the tall, black, wrought-iron gates, releasing girls in white, pleated uniforms and red ties into the bustle of Bangalore’s fashionable Brigade Road.

My sister Angel and I are carried along with the flow, a jumble of elbows and legs. Angel is seven; I am ten.

I spot our ayah’s enormous yellow-and-red striped umbrella before I see her. Khaja is one of Burrimummy’s oldest servants; she is here to take us on the short walk home. She is a tall, lantern-jawed woman whose thin cotton sari does nothing to disguise her angular limbs. The sharp point of her umbrella is a weapon dodged by drivers, ayahs and orderlies. She looks after Angel, not me. She gives me a warning look.

Ignoring Khaja, I duck behind the other girls and shove towards the vendors’ carts where flies circle sliced green mangoes and cucumbers. I push between the jumping schoolgirls waving their money and thrust a crumpled rupee note at the vendor.

I return with sour cucumber in powdered chilli pepper, wrapped in newspaper. Salty water seeps through, making my hands sticky.

Khaja holds Angel with one hand and balances the umbrella over her head.

‘Baby, baby, don’t eat that,’ she screeches at me.

I bite into the fly-infested vegetable.

‘Want some, Angel?’

‘No, Baby!’ Khaja cuts in sharply. ‘Your grandmother will be angry. Angel baby will get sick.’

Angel lives with Burrimummy all the time.

I am sent to Burrimummy for months at a time when Mummy is tired. Mummy says army life is a strain with constant moving and all the cocktail parties.

We pass Bishop Cotton Boys’, a rectangular redbrick building next to our school. Mummy can’t manage Winky either because he’s impossible to control. When Mummy was unpacking her china in Chandigarh, he said, ‘I can jump over glass. Want to bet?’ Before she could stop him, Winky took a giant leap and landed in the middle of her dinner set, sending glass everywhere and ended up with a bleeding chin. Mummy had had enough and put him on a flight to Bangalore to live with Burrimummy.

I stop to look back at the boys walking out of Bishop Cotton Boys’ School dressed in white shirts, blue ties and khaki shorts, hoping Winky will be one of them. But he never is, even though at fourteen, he sometimes gets to leave the compound. Winky boards at Bishop Cottons because he was rude to Burrimummy, calling her a Pakistani spy after Burrimummy caught him shooting rubber bands at the servants’ quarters from the terrace. I was standing with him when she hauled him down and booked a trunk call to Simla, bellowing at Mummy for bringing up her son like an infidel. She wouldn’t keep her Hindu grandson for a moment longer under her roof. ‘Do what you think is best,’ Mummy told her. Burrimummy marched Winky to Bishop Cottons and admitted him as a boarder with immediate effect. I begged and begged her, but she refused to take him back.

I don’t know why, but I always felt afraid I wouldn’t see Winky again. I remember listening to the radio news with Mummy when we lived in Guwahati. Mummy screamed. A school bus had turned over on a slope near a tea plantation, and children may have been killed. It was always raining in Guwahati, and I climbed up on a stool watching the rain on the window and sobbed until Winky came charging in.

Winky has lived with Mummy and Daddy the longest, moving with them from Calcutta, where he was born, then Guwahati, where I was born. We got broken up when Angel was born in Sagar, and Burrimummy came to look after Mummy and took Angel away at just five days old and never gave her back. We four kept moving to Chandigarh, Bangalore, Simla, but Angel stayed in Bangalore – that’s why she’s a civilian, we military.

Winky and I are always last in class because of the changing languages in the different states we’ve moved to. Apart from English and Hindi, we need to learn Punjabi, Himalayan and Kannada. The resulting incomprehension bleeds into maths, geography and history. I feel I don’t belong here or anywhere. In class I pretend I’m not me, and the not-me is not there. That’s why I don’t mind being short-sighted. I don’t mind the foggy blackboard because it reminds me of Simla before the snowfalls.

Our teachers are Irish nuns, Anglo-Indian and South Indian women. Only two are men. The PE teacher is stern-looking with sensual lips and a moustache; the male art teacher has a pink harelip. A week ago, he drew a bird in ink and smudged it as he went along. That smudge was the only thing that made sense to me. When a teacher draws attention to one of my shortcomings – forgetting homework, not copying from the blackboard, not understanding – I imagine floating outside, feeling sunshade and breeze and hear the teacher from far away through the chattering of insects. I hear no shouting and feel no shame.

Even when Daddy was posted to Bangalore, and Winky, Mummy and I lived together in St John’s Road, near the officers’ mess, Angel never came to stay, except for one night when Burrimummy, wearing a crisp white linen sari, dark glasses and her lips in a flattened red line, brought Angel from Rest House Road, looking as if she was going to a funeral. Mummy met them at the door in her dressing gown, halfway through getting ready to go out, as she and Daddy did every evening. When Burrimummy drove away out of the circular driveway, Angel strained to watch her car long after it was gone, standing on the veranda like a statue, refusing to come in. Mummy asked me to take her to the dining room where dinner was laid out, and she took my hand, but once inside Angel walked backwards until she was standing against the dining room wall and wouldn’t touch her food, so before Mummy and Daddy left for a dance at the officers’ mess, Mummy gave her my doll, which had blonde curly hair and was almost two-feet tall. I brought her to my bedroom and let her hold my doll in my bed.

I thought how nice it would be if she lived with us. With my arms around her, I tried to convince her St Johns Road was a place of fun, but she said it looked like school, with halls and wooden floors, so I told her of the nights Mummy and Daddy gave parties, how the floors shone, and silver gleamed like mirrors. Lots of people came; the army band played, and the grownups danced in the drawing room; wandered about in the garden and drank and swayed and kissed people who weren’t married to them. Once I saw a couple near the swing under the tamarind tree; they looked as if they were wrestling, but now I knew what it was, and I told Angel I would tell her if she lived with us. I told her Mummy was always the loveliest of them all in her chiffons and neon silks; how Daddy looked like the actor Dharmendra in his dark evening suits. I told her the orderly played Snakes and Ladders with me when they went out.

Angel looked at me with large...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.7.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84523-569-X / 184523569X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84523-569-7 / 9781845235697 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich