You Are Here (eBook)

412 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-7453-9 (ISBN)

Larry Goeller is a retired government analyst living in Alexandria, Virginia. Originally from New Jersey, he's lived in the Washington, DC area since getting his PhD in Physics in 1986. He is married with adult children and spends much of his time reading and developing new skills, including writing, making YouTube videos, and playing the bass. He still owns the motorcycle.

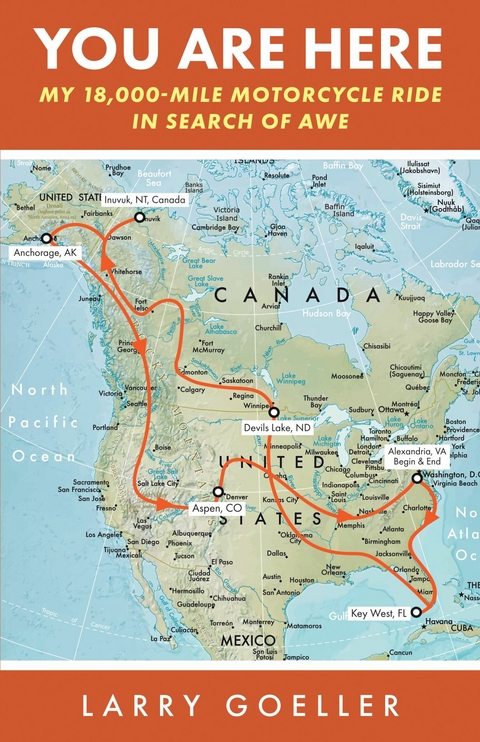

In 2015, at age 57, the author set off on a motorcycle for his "e;journey of a lifetime."e; He took three months off from his work as a government analyst to ride across North America, and to document what he saw and felt. Inspired by a series of quasi-extreme challenges, he planned a route that connected Key West, Florida to the Arctic Ocean, including several thousand miles of nerve-wracking, unpaved roads in the Canadian sub-arctic and arctic. Traveling mostly alone, he was ultimately gifted with a profound sense of awe, finding-literally, figuratively, and spiritually-his modest place in the universe. Though carefully planned, his journey included many surprises, from dire to delightful. Each near-death experience felt like a "e;strike,"e; but each unexpected treasure, a stroke of serendipity. The theme that connected many of his planned excursions was the Earth's natural history, but in addition to dozens of the unique natural features and biomes of North America, he also encountered a cowboy on a triceratops, an oasis-slash-truck stop in the middle of nowhere, and a one-night-only concert by a favorite artist he'd never planned to see. At every stop, he talked to people, and everywhere he went, they were fascinating. Partly inspired by, and partly in spite of Robert Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, this book is an account of a modern-day odyssey that is sure to resonate with readers who have ever traveled outside of their comfort zone, or who dream to do so someday.

4. The John Muir Trail

In June 1980, near the end of my brief but influential ten-month residency in California, I put what little I owned, including the motorcycle, into storage. I planned to drive it all in a U-Haul in late August to Houston, where I intended to try grad school again, this time at Rice University. I could have remained at SRI throughout the summer, but again, I chose odyssey.

The previous summer’s experience on the AT had not burned me out on hiking—in fact, just the opposite. I apparently believed that my moderate AT experience meant I was ready to take my hiking to the next level. I became enamored with the idea of hiking the 210-mile John Muir Trail (the JMT) in the High Sierras of California, and planned accordingly. The JMT passes through three national parks: Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia. That desire to walk “out on the wire” again—this time, a distinctly more challenging wire—burned intensely within me, and I relished it.

The first three days of hiking in Yosemite National Park were fabulous. I was with Mark, another college friend who had become a grad student at UC Berkeley, and we did maybe thirty miles of hiking within the park boundaries. I felt pretty strong, even in the thin air.

Mark could only stay for a few days, and we planned to part ways at a manned campground above the valley. He intended to go back down into Yosemite Valley, while I would continue along on the JMT. But when we got to the campground at the fork, we were informed that the trail was closed due to heavy snow at higher altitudes. It was July 1! So I hiked back down into the valley with Mark, and the next day, he dropped me off at the JMT “town” of Tuolumne Meadows before returning to the Bay Area. My plan was to wait there, sleeping in one of the large four-person canvas tents available for a fee during the summer, until the trail reopened.

That happened the next morning, and without hesitation, I set off down Lyell Canyon. This first stage was easy, level walking at about 8,700 feet in altitude, below the snow line, with magnificent scenery all around. This lulled me into a false sense of security. In retrospect, the fact that none of the other people staying in Tuolumne joined me probably should have tipped me off. But I had come to think of myself as a guy who would jump in and figure the rest out on the fly. What could possibly go wrong?

When the canyon ended after several miles and the climb up into the higher elevations began, things got hairy. Several feet of snow still covered everything over about 9,200 feet. Hiking through snow is like hiking through sand—exhausting, even without the climbing or the high-altitude aspects of the situation. The air wasn’t that cold—about 50 or 60 degrees—but the snow obscured the trail itself. Had I run into these conditions earlier, I might have turned back to wait a few more days. But I had already hiked close to ten miles, and felt I had come too far to turn back without at least trying. Once I began this trend, I continued to throw good money after bad. My confidence started to evaporate.

Unlike the AT, where the trail blazes (markings) were painted on trees with unmistakable white paint, those on the JMT were designed to appear less artificial. The JMT blazes were typically rectangles cut into tree bark (below the timber line) with a hatchet. But as time passed and the trees healed, the blazes eventually looked remarkably similar to naturally occurring damage. Above the timber line, the trail marks were painted onto rocks, and therefore were now buried under snow. No footprints marred this freshly fallen blanket. As a result, in this pre-GPS age, I spent the rest of that day and the next three being unsure of where I was, even with my compass and detailed topographical (“topo”) maps. I was now alone. For better or worse, I kept going.

The four days I spent alone in the high-altitude, snow-covered regions of the Sierras were the most intense of my life. Large parts of my mind seemed to shut down, and I focused almost entirely on navigation and trying to haul my life support equipment though this hostile environment. Occasionally, my higher-level mental functioning was forced to surface, due to the sudden manifestation of some utterly spectacular feature. These views, while stunning, did not bring delight so much as a sense of low-level terror. Do I have to go over that mountain? I’m going to have to cross this swiftly flowing creek of ice-cold water… The ice on the lake at the bottom of this steep, icy slope is not thick enough to hold my weight if I lose my footing…. My mood had morphed from that of a brash challenger to a mix of angst and determination, flavored with a subliminal but more or less continuous sense of awe.

The third night, the Fourth of July, 1980, I pitched my tent on a bare spot on a mountain a quarter mile from where I figured the trail was, at an elevation of almost exactly 10,000 feet—still my personal altitude record for camping out. The temperature dropped quickly when the sun set, and in the morning, there was frost on the inside of the tent. Vivid dreams.

On my fourth solo day, I became seriously lost in the Sierra Wilderness for the second time. I eventually recovered, and then made a descent down a portion of the JMT that was “only” 2,000 feet, but felt like more. During that long climbdown, the air temperature rose from maybe 50 degrees Fahrenheit to about 90 degrees.

That particular valley contains Devils Postpile National Monument (an unusual geological feature) and, probably not coincidentally, the manned outpost of Reds Meadow. This “backcountry lodge” is connected to civilization via a dirt road and a shuttle bus. I don’t remember consciously deciding, but somewhere in that long descent, it was determined—click—that I was going to leave the JMT at that point.

I had covered only about thirty-five miles since Tuolumne Meadows, but that trek involved close to thirty hours of actual hiking, and many more staring at topo maps. The snow looked like it would hang on for weeks at the higher elevations, and I felt like I had used up all my luck. And the thought of climbing back up those 2,000 feet back into snow felt both daunting and demoralizing.

I took the shuttlebus from Reds Meadow to the town of Mammoth Lakes, and from there caught a larger bus to Reno, Nevada, on the east side of the range. The next day, I caught another bus back to San Francisco. I had quit.

In the days that followed, I felt strong but ambivalent emotions. On the positive side, I acknowledged to myself that what I had managed to do in those four days was nontrivial. My youthful self was kind of proud that I hadn’t turned back, or scanned the skies for passing aircraft to signal that I needed rescue. I had recovered from being lost (twice), and walked out under my own power.

Still, this felt very different than leaving the AT the previous year. I was humbled. I remember looking out the bus window on the way to Reno and staring at the snowcapped Sierras. A week earlier, I had looked at a similar view with eagerness and elation. Now I felt something close to dread. Tail tucked between my legs, I felt grateful to be a paying passenger on a Greyhound, rather than a hiker, up there, and in that.

Looking back on that experience years later, what I recalled was the intensity of the experience—hour after hour, day after day. Hiking on the AT had been beyond my skill level when I started, but I mastered it fairly quickly—at least at the relatively modest pace of ten miles per day. The JMT was beyond my skills at a whole different level.

In the snow-covered Sierras, I felt like an ant on a volcano; I felt insignificant in this environment. I badly wanted to stay alive, but it was viscerally apparent to me that my surroundings—which were vastly larger and more powerful than myself—didn’t care whether I did or not. I realized that the intensity of my emotions was in part because I was alone. Had someone been with me at that stage, I think we might have kept each other calmer.

But here’s the thing: the very intensity of what I felt enabled me to sometimes feel incredible awe at my surroundings. I will never forget seeing Mount Banner and Mount Ritter, with snow on the few narrow surfaces level enough to allow it, rearing up like light purple giants over an ice-covered Thousand Island Lake. Of finally making it over a mountain pass a thousand feet above the tree line. Of crossing engorged streams filled with roaring, freezing-cold meltwater, in bare feet. I may have been in a perpetual state of angst, and occasionally terror, but I felt intensely alive.

As the years passed, my mind regularly returned to one particular event during that four-day stretch. I was climbing out of a valley on my third solo day on the JMT, below the snow line, where the trail was identifiable. It was midafternoon, and I wanted to cover another three or four miles before stopping for the day at a lake I identified on my topo maps. That meant climbing back above the snow line—so again, no trail, no footprints, and no definitive blazes.

I knew where I was coming from, and I had a compass for direction. But still, I was wandering up the side of a mountain in the wilderness without a trail, probably with more bears than people in the ten square miles around me. I stopped often in the deep snow to check the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-7453-9 / 9798350974539 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich