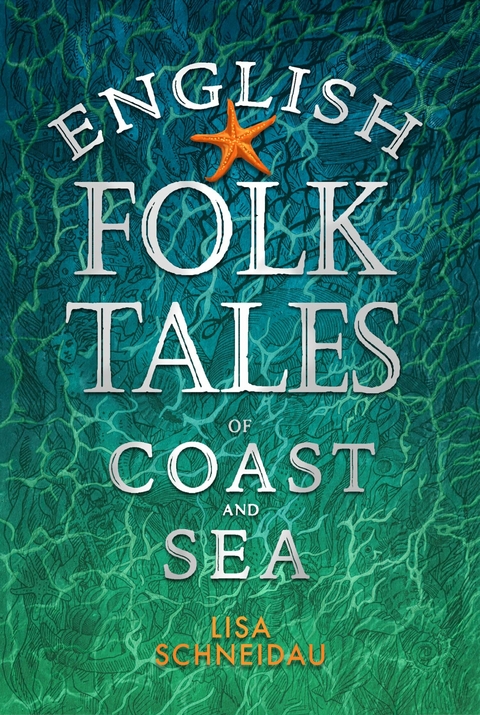

English Folk Tales of Coast and Sea (eBook)

192 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-424-6 (ISBN)

LISA SCHNEIDAU is a professional storyteller, sharing stories that inspire, provoke curiosity and build stronger connections between people and nature. She tells stories at theatres, festivals, schools and events all over the UK. Lisa trained as an ecologist, and for twenty-five years she has worked with wildlife charities across Britain to restore nature in land, river and sea. She is the author of Botanical Folk Tales, Woodland Folk Tales and River Folk Tales, all published by The History Press. She lives on Dartmoor in south-west England.

2

SAINTS AND SINNERS

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1798

The sea is a place of wild extremes. It can be benign and wondrous and giving. Alternatively, in the words of Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities, ‘The sea did what it liked, and what it liked was destruction.’ The transition from one state to the other can be swift.

No wonder so many folk tales from the English coast tell of the moral extremes represented by holy men, and Old Nick, the Devil himself. Both saints and devils are used to explain the existence of coastal formations or strange wonders. As the stories show, the dividing line between good and evil is not always a clear one.

THE HOLY ISLAND

The island of Lindisfarne, just off the Northumbrian coast, is a wildlife-rich jewel with a sacred and colourful heritage. The priory on Lindisfarne was founded in the year AD 634. The Viking raid on Lindisfarne in 793, deliberately targeting a holy place for the Christians, is considered to be the beginning of the ‘Viking Age’. Even following the dissolution of the monasteries in the sixteenth century, and religious changes since that time, this ‘Holy Island’ remains a place of pilgrimage today for Christians and nature-lovers alike. The mudflats, dunes and rocky coast of Lindisfarne are designated as a National Nature Reserve to protect internationally important populations of wintering birds.

Eider ducks, common on the coast around Holy Island, are also known in Northumberland as Cuddy’s duck, after St Cuthbert. Eider ducks are large, elegant birds that nest on the rocky shorelines of northern Britain. The males are black and white with a comical call, the females brown. Eider were economically valuable because of their soft feathers (eiderdowns were called this for a reason). Tradition says that Cuthbert was fond of eider ducks and issued formal orders for their protection on Lindisfarne.

Ravens, the largest of the crow family, are happily increasing their range again across the British Isles. Ravens have a long and dastardly folklore. They are said to be birds of ill omen and malevolent intent, as well as bringing protection. The collective noun for ravens is an ‘unkindness’ or a ‘conspiracy’. I think their dark reputation is a pity, for the ‘cronk-cronk’ call and playful flight of the raven betrays a sharp intelligence and humour.

St Cuthbert (634–687) is an important Christian saint in the north of England and southern Scotland, and the patron saint of Northumbria. Cuthbert was bishop in both Lindisfarne and Melrose in Scotland. He travelled widely in his missionary work in these very early days for Christianity in the British Isles, and was well known for his generosity and wisdom; however, he lived a very austere and simple life, often as a hermit. His example has inspired people through the ages. Cuthbert’s remains have now (hopefully) found their eternal rest at Durham Cathedral, following the long journeys described in these tales.

Bartholomew (died 1193) was a Benedictine hermit who received a vision of St Cuthbert and spent most of his life in seclusion at Lindisfarne Priory, newly restored at that time after the Norman conquest.

Eider ducks gather on the rocks in the springtime at Holy Island, fearing no humans. They build their nests everywhere, and everyone knows not to disturb them; the mothers lead their brown fluffy ducklings to the sea when they are very young.

Many years ago, a mother eider was leading her brood of little ones from the rocks to the sea, when one of the ducklings fell down into a great crevice in the rock. The mother stared in distress for a few moments, then turned and, bidding her children to stay, went to find the hermit Bartholomew.

She tugged at the hem of his cloak with her bill, and he got up, worried that he might be disturbing her nest. But she kept tugging at the cloth of his cloak, and he realised that the eider wanted for something. He followed her out to the rocks and when they got to the place where her little ones were still patiently standing, she pointed with her bill towards the crevice in the rock.

Peering down, Bartholomew could see the little bird with its wings outstretched, clinging on for dear life. He clambered down and rescued the little thing, of course, and the glint in the eider’s eye showed she was pleased.

Then the mother eider continued on her way leading her brood down to the sea, and the hermit Bartholomew went back to his oratory.

One morning, Cuthbert noticed that the thatched roof of Lindisfarne Priory, made with love and toil by the holy men of the island, was being ripped apart. This crime was not committed by humans, but by two ravens who were seeking to make their own home from the thatch, and were merrily pulling out the straw and carrying it off as nesting material.

Cuthbert spoke sternly to the ravens, and asked them to collect their nest stuff from elsewhere on the island. Did they listen? Do ravens ever listen? ‘Cronk, cronk,’ they called out, like so much raven-laughter.

Cuthbert was not impressed. ‘In the name of the Lord,’ he cried, ‘be off with you, and never return to this place that you have spoiled.’

The two birds bowed their heads, as if they had been dismally scolded, and then spread their great black wings and flew away.

Three days passed with no sign of the troublesome two. But towards the end of the third day, as Cuthbert was digging in the vegetable field, one of the ravens landed at a respectful distance, his bill bowed down to his claws and his mumbling croak muted and humble.

Cuthbert well understood the gesture, and gave the raven permission to return. It flew off, and soon returned with its mate, both of them carrying gifts: hunks of hog’s lard, which Cuthbert graciously accepted.

For many years after that, the same ravens lived alongside the brethren of the priory on Holy Island, and neither party caused any annoyance to the other.

Cuthbert died after a painful illness. His body was buried on Lindisfarne on the same day, and everyone prayed for him to find eternal peace there.

Their wish was granted for over a hundred years, until the Norsemen came with their axes and their blades. For one day in early summer, holy blood ran in rivers and mingled with the salt water. The bodies of monks were trampled in the road like dung; others were taken as slaves. All the buildings of the priory were burned to the ground, and the holy treasures stolen.

Some monks had foreseen the great pagan terror and managed to escape. One of them had remembered the words of St Cuthbert: ‘Rather than submit, I choose and wish that you take up my bones, fly from these places, and stay wherever God shall provide for you.’

Time was short. A wooden box was hurriedly made and the remains of the great saint were laid within it. Then, carrying the precious cargo, the monks fled the island to the mainland.

For seven long years, the monks travelled from place to place across the North Country. Sometimes they carried Cuthbert’s coffin on their shoulders, and sometimes on a cart pulled by a horse. Always they travelled in fear of the Norsemen, and at one point they even tried to flee to Ireland, but a storm drove them back and they continued their journey in search of a place to find rest for the great saint.

One day they reached a hill not far from Chester-le-Street, and there the wagon carrying the coffin got stuck in deep mud. They tried yoking up more horses and even oxen to the cart, but nobody could shift it. Was this a sign that the good man wanted to stay?

For three days the monks fasted and prayed for guidance, and then one of them heard a voice from nowhere that said, ‘Take the saint’s body to Dunholm.’

‘Where is Dunholm?’ None of the monks had ever heard of the place.

Then a milkmaid passed by the cart, driving her cows home to milk. Another woman came by in the opposite direction, and called out to the first, ‘Neighbour! Have you seen my dun cow with one short horn and one long? I have lost her.’

‘Yes, I have,’ came the reply, ‘I saw her just now, wandering at Dunholm.’

The monks were excited at this. ‘Please show us the way to this place of Dunholm.’ They pulled the horse forward and tried to move the wagon one more time, and to their astonishment it came free and started to roll again, as if the axles of the wheels had been freshly greased.

Horse, cart, saint and monks followed the woman along the tracks and through the trees, to a beautiful, craggy place, surrounded by trees. When they looked down they could see the river twisting round and almost circling where they stood. This was the perfect place of protection. Next to the spot where the woman’s short-horned dun cow stood, the monks fell to their knees and prayed that their journey had reached its end.

The monks laid the saint’s bones to rest in the spot at Dunholm, and built a humble wooden church around the shrine for their beloved Cuthbert. The church was enlarged and improved over the years, until it became the great Durham Cathedral.

St Cuthbert’s bones then found peace for a few hundred years, until yet another invasion of England. This time, William of Normandy had seized the land for himself, and all the English...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Folk Tales |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Märchen / Sagen |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | coastal communities • Coastal Stories • David Wyatt • Ecology • english coast • Fairy tale • Fairy tales • Folklore • Folk Tale • Folk Tales • Legend • Legends • Maritime • Myth • Myths • ocean legends • ocean myths • salt sea • sea godesses • sea gods • sea myths • society for storytelling • Storyteller • storytellers • Storytelling |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-424-X / 180399424X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-424-6 / 9781803994246 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich