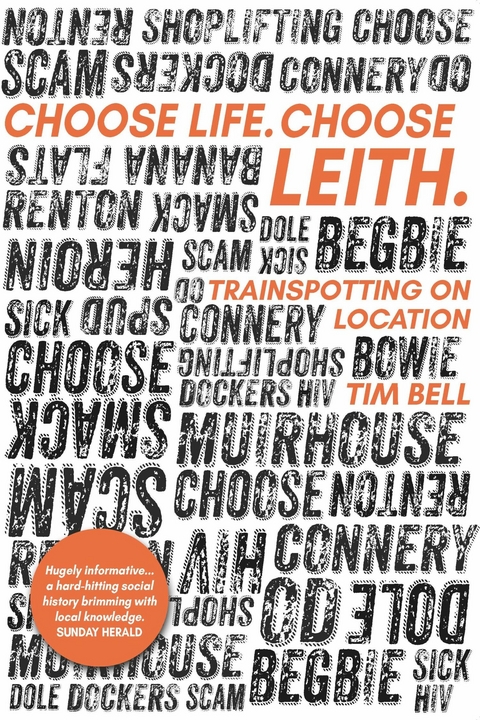

Choose Life Choose Leith (eBook)

282 Seiten

Luath Press (Verlag)

978-1-80425-154-6 (ISBN)

TIM BELL is originally from Northumberland, but has lived in Leith since the 1980s. Having lived in the area at the time Trainspotting was set, Bell has seen the change in Leith and the troubles it has faced. Bell, who runs Trainspotting tours in Leith, has a thorough knowledge of the book, the play and the film, as well as the history of Leith, and through his book wanted to put Leith back at the heart of Trainspotting, back where it belongs.

CHAPTER 1

Leith Central Station

YOU CAN GO TO exactly the spot where the photographer stood to take the shot on page 29 of Leith Central Station and the Foot of Leith Walk. The horse-drawn tram dates it to no later than 1904, that is within a year of the opening of the station. You are standing in the heart of Leith and at the heart of Trainspotting. The Heart of Leith, the Foot of Leith Walk, and Leith Central Station all their have distinctive meanings but they can easily be pretty well synonymous.

Irvine Welsh uses this location to pin together his story Trainspotting. The small figure on the far pavement at the lower right edge of the shot stands at the taxi rank where Renton fulminates in the first episode: ‘Supposed to be a fuckin taxi rank. Nivir fuckin git one in the summer… Taxi drivers. Money-grabbin bastards…’ (p.4).1 Leith Central Station is the most emphatically identified location in the entire book. Directly opposite the taxi rank, out of sight up the opening at the end of the terrace beyond the third awning, Renton and Begbie go up the ramp that ran along the gable end into the derelict station at first floor level, for the ghostly figure to suggest that they are there to spot trains. One of the most moving tours I ever did was with a recovering alcoholic. On what remains of the ramp I talked him through the literary situation, and I had to leave him alone with his thoughts for quite a while as he looked across the street and considered the implications for himself of being brought back to where he began.

When I came to live in Leith in 1980 an old man told me that ‘the Fit ay the Walk’ was the heart of the town. There were no changes from this photograph then, but now you will see that the ridged glass roof to the left of the station clock tower and the railway bridge a few hundred yards up Leith Walk have been removed. I was puzzled. I found a dispiriting 1960s shopping centre called New Kirkgate behind and to the right of where the photographer in the 1900s stood, with an unprepossessing residentialised walkway on the other side of it, heading away to the north. I had seen the same many times before, in towns around Britain. There was endless traffic on the junction in front of me, and the station behind the faded facade under the clock tower that dominates the photograph was obviously derelict and useless. But with a little local knowledge and a longer view, I gradually discerned what the old man meant.

Kirkgate – that’s Church Street in modern English, and the name tells you the street has been there for many centuries – ran to the edge of the crowded medieval town at the 16th century defensive town wall at St Anthony’s Gate, which was over the right shoulder of the photographer. The broad boulevard in front of the camera was built as a military defence and line of communication in the 17th century Cromwellian war. When the army left, it became a fine high route to Edinburgh, provided they kept horses and carts off; hence the name Leith Walk. In the days before the tyrannical motorcar, this broad confluence was a natural focal point in the town. It was the start or end point for many a march and rally for well over a century. The centrality was already in the parlance: Central Hall was there before Central Station. In 1907 they deliberately placed the statue of Queen Victoria, which comes into Trainspotting, in the heart of the town; it’s just off the shot to the left. Now the Heart of Leith is reduced to this broad pavement where the camera stood, 30 yards by 50 yards, not much to call the heart of a town. It’s a favourite spot for canvassers. There’s some seating. It catches the best of any sunshine that’s going. There’s a municipal Christmas tree here every year.

Whether it was arranged or not, the potency of this image lies in the line of boys and men, all with their caps on, stretching from the heart of the throbbing old town, across this social arena and fulcrum of the town’s comings and goings, to Leith’s magnificent entry to the wider world. This brings us to Leith Central Station, so central to Trainspotting. To have a full appreciation of the metaphor Welsh works in lifting an obscure, enigmatic word from a page towards the back of the book onto its title page, we need an understanding of its massive, useless, elusive, vainglorious and dysfunctional purpose and presence at the heart of Leith.

*******

Leith Central Station was a bastard. In 1889 the North British Railway Co. (NBR), wishing to thwart rival Caledonian Railway Co.’s (CR) proposal to run a loop to Leith docks, and, having invested heavily in the new Forth Bridge and needing to increase its capacity through Princes Street gardens, undertook to build a dedicated passenger line and station in Leith in order to have its way on both counts. Corporate hubris and the absence of any strategic planning was one parent.

A single-track line with a ticket office and a shed on the platform would have been enough. The town had neither the density of population nor a sufficient hinterland, the nearby port notwithstanding, to justify one of the biggest stations in Scotland at almost three acres, and the largest to be built in Britain in the 20th century. Leith Burgh Council didn’t want a level crossing at Easter Road, so at vast expense the company built a bridge and brought the trains in at first floor level; hence the ramp at the Leith Walk end. The Council wanted a clock tower; the company provided the one we see today. The station had several sidings, four platforms, generously proportioned waiting rooms and a large concourse. No-one knows why they had the wonderful roof made by Sir William Arrol, who had the Forth Bridge, Tower Bridge, London, and North Bridge, Edinburgh, to his credit. He wasn’t cheap. The sheer size and extravagance of Leith Central Station is the unknown parent.

The people of Leith had no reason to concern themselves with any shortfalls of their glorious new access to the outside world. The enormous area, free of internal division and interruption of any sort, together with the great height of the roof which permitted excellent natural light throughout, created very special effects indeed. And the name: was it not something to be conjured with? Edinburgh and London didn’t have a Central station. Glasgow and New York both did. And Leith! An ordinary suburban station it could never be. This place was a cathedral of visions of distant places and triumphant homecomings, an emporium of travel.

Mr John Doig owned The Central Bar at numbers 7 and 9 Leith Walk, immediately to the left of the nearest awning in the photograph. There were two small lounges at the rear of the main bar, from which there was easy direct access up to the platforms. The interior was attended to in fine style and, for the price of a drink at the bar, you can still appreciate it, unaltered, in all its glory. Look at the paintings amongst the highly elaborate tiles, woodwork, plasterwork, coloured glass and mirrors: the Prince of Wales (shortly to be king) playing golf; yachting at Cowes Regatta; hunting with pointers; and hare coursing. Evidently Mr Doig was a royalist. The fabric is now protected, as is the whole frontage from the foot of Leith Walk round the corner into Duke Street, with the clock tower on the corner. Welsh often drank here, and it is the pub that best fits the description in ‘Courting Disaster’ as the location for the second après-court celebration from where Renton goes to Johnny Swan ‘for… ONE FUCKIN HIT tae get us ower this long hard day’ (p.177).

Not to be thwarted in the end, Caledonian Railway Co., within a few months of the opening of NBR’S Leith Central, opened its own line to the east docks by a circuitous route, crossing Leith Walk by the bridge a few hundred yards up Leith Walk in the distance in the Edwardian photograph. Leith Central Station became operational on 1 July 1903 with no formal opening. The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch sniffed that the huge station for a single train was like a two-storey kennel for a Skye terrier. The bread and butter business was the ‘penny hop’ to Edinburgh, but when the Leith and Edinburgh tram systems were unified in the early 1920s a big hole was knocked into the customer base. However, during the 1920s and 1930s, they ran a good service to Waverley and round the southern Edinburgh suburban line. And, as Renton correctly observes as he pisses in the dereliction half a century later: ‘Some size ay a station this wis. Git a train tae anywhere fae here, at one time, or so they sais…’ (p.308). The Leith Member of Parliament, George Mathers, would proudly board his train to London here; first stop Edinburgh Waverley. They ran football specials, beer safely on board, to Wembley, London, for international matches. And you could go to Glasgow in the west or Aberdeen or Inverness in the north.

But the services gradually declined. By the end of the 1930s the station not much more than half a mile away, the Caley at Lindsay Road, offered 37 daily trains to Edinburgh while there were only 27 from Leith Central. Many of the trains leaving the Central were single carriages behind the engine, widely known as The Ghost Train. One engine driver recalled Leith Central Station shortly before the war: ‘…this great edifice was like a sanctuary, a retreat from the hustle and bustle of places like Waverley Station. Sitting on my engine at Leith Central I have contemplated its spacious emptiness, not a soul in sight, only the quiet murmur of steam and warm fireglow…’2 Unglamourous and under-used,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Anthologien |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | Culture • Edinburgh • History • Identity • Leith • Scotland • Scottish • Trains • Trainspotting |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80425-154-2 / 1804251542 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80425-154-6 / 9781804251546 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich