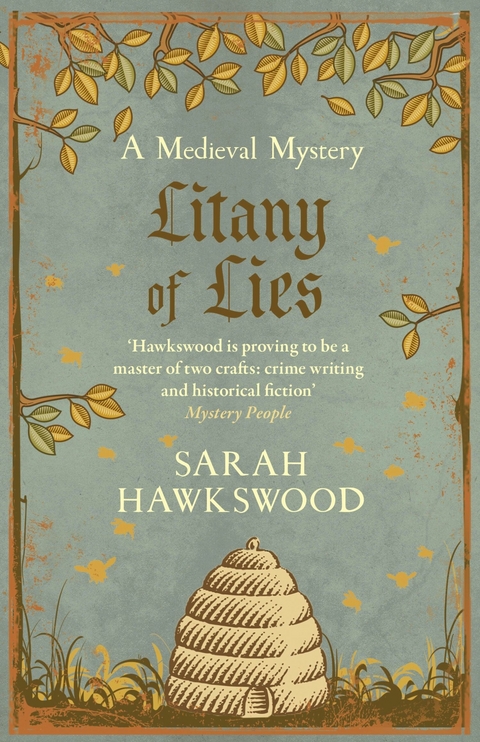

Litany of Lies (eBook)

384 Seiten

Allison & Busby (Verlag)

978-0-7490-3103-9 (ISBN)

Sarah Hawkswood describes herself as a 'wordsmith' who is only really happy when writing. She read Modern History at Oxford and first published a non-fiction book on the Royal Marines in the First World War before moving on to medieval mysteries set in Worcestershire.

Midsummer, 1145. Walter, the steward of Evesham Abbey, is found dead at the bottom of a well pit. The Abbot, whose relationship with the lord Sheriff of Worcestershire is strained at best, dislikes needing to call in help. However, as the death appears to have not been an accident, he grudgingly receives Undersheriff Hugh Bradecote, Serjeant Catchpoll and Underserjeant Walkelin. The trio know to step carefully with the contentious undercurrents at play. As the sheriff's men investigate the steward's death, they discover that truth is in short supply. With the tensions between the Abbey and the local castle guard reaching boiling point, another killing will force the investigation down a dangerous path.

Sarah Hawkswood describes herself as a 'wordsmith' who is only really happy when writing. She read Modern History at Oxford and first published a non-fiction book on the Royal Marines in the First World War before moving on to medieval mysteries set in Worcestershire.

A baking hot day, one that had mellowed into an evening still too warm and airless for comfort, was drifting into an uncomfortable, sticky night. June had been a month of blazing sun that had seen the Avon’s level drop, revealing her banks like a wanton flaunting her ankles, and flow lazily, as though it also found the heat exhausting. Only the visiting swallows and house martins seemed to be as energetic as always, busily raising their broods beneath the thatched eaves of the houses. Now, as the soft dark of a short, summer night descended, their screams and chirrups had been replaced by the faint flutterings of bats flitting about for moths, weaving between the houses and swooping over the parched grass of the Merstow green. At the north-west corner of the open ground a pair of posts and a crossbeam stood guard over a hole in the earth, where a well was part dug. The spoil bucket stood beside it, the rope coiled tidily within it like a sleeping adder, and off to one side was a neat pile of stone for the well lining, and the blocks from which the local mason was hewing them. Two men stood close by, barely a pace apart, glaring at each other, arguing in low voices.

‘What sense is there to this?’ the shorter man growled, his features growing indistinct in the rapidly fading light. ‘It would not be thought odd for us to be speaking together in passing. Think yourself fortunate I came, for I does not need to obey a summons from the likes of you at a foolish hour.’

‘What I have to say will not be to your liking, though I care not, and you were never one to hide your thoughts. This is safer, and by neither’s hearth, which seems fair.’

‘Fair! Ha! When did you ever do “fair”. So go on, say what you need and let me get to my wife and my bed.’ The shorter man hunched his shoulders grumpily.

‘I need more.’

‘Need? What for? Is your position not high and mighty enough for you? Does you want the trappings of a lord?’

‘Why I want it is not your concern. All you need to know is that when the rent falls due Midsummer Day, there is six shillings to pay on top of the rest.’ The taller man folded his arms and looked obdurate.

‘Six shillings?’ The shorter man was taken aback and repeated the sum.

‘Yes. Your business thrives. You can afford it.’

‘No.’ The refusal was blunt.

‘You can afford it, I say.’ The taller man persisted.

‘No. I will not give you another six shillings. In fact, I will give you nothing at all.’

‘What do you mean?’ It was the taller man’s turn to be surprised.

‘’Tis simple enough. You have had all you will get from me, even if you spouts your lies to turn folk against me. It don’t scare me no more. You can accept that, or I will go to the lord Abbot with the truth of what has been going on.’

‘He would not believe you.’ The taller man snorted derisively. ‘Your word against mine? No contest. What is more, if you thought he would do so, you would have gone to him at the first.’

‘Oh, do not be so sure. I now knows more than you think.’ It was more guessing, but the man was not going to say so.

‘But the lord Abbot would not believe a man who is ever late to pay his rent.’ The taller man wished he could see the other man’s reaction to that.

‘I pays on time. You know that.’ Outrage made the man’s voice rise, and the taller man hissed at him to lower it.

‘You pay me, but the abbey rent rolls show you have been short these last three quarters and only my good word has kept you from eviction.’ The tone was triumphant, gloating, and he unfolded his arms to poke the shorter man in the chest with a long forefinger.

‘Your good word! You bastard!’ The shorter man launched himself towards the other and the pair tumbled to the dry earth, both half-winded by the fall. They rolled, like puppies at play, except this was in deadly earnest, each trying to inflict as much pain as possible upon the other. It was chance that they rolled towards the stone pile, but the hand that grabbed a worked piece of it moved with intent. There was a sharp crack, and one of the men slackened his hold and went limp. His opponent dragged the inert body to the well hole and cast it over the edge to drop the fifteen feet or so to the bottom of the workings. For good measure, he cast the lump of stone in after him. Breathing heavily, and with hands that shook a little, the victor went home to his bed, and disturbed slumbers.

Reginald Foliot, Abbot of Evesham, sighed, and rubbed his temples with the tips of his long, pale fingers. His relations with William de Beauchamp, lord Sheriff of Worcestershire, were not without complications, and de Beauchamp was a tetchy man who did not trust clerics, especially clerics with noble connections. Before Chapter he really must formulate how he was going to complain, yet again, about the theft of abbey property by the Bengeworth garrison, who had clearly crossed the bridge in the dark hours, scaled the wall, ‘his’ newly completed wall, built to protect the abbey in dangerous times, and stolen two casks of wine, quite good wine at that. The townsfolk of Evesham would not be so bold, and the garrison were a drunken lot, for the most part. The lord Sheriff would deny that it was his men, and say no proof could be brought, but it was always his men. The fact that the garrison changed regularly did not seem to make a difference. The abbot wondered if he ought to have stipulated the wall should be even higher, and sighed again, resolving to lead the brethren in a prayer after Chapter that God would put charity in the hearts of the sinful.

There came a knock upon the door, and at his bidding to enter, a youthful brother almost fell over the threshold in his haste to come in. Abbot Reginald frowned.

‘Those things which we do in a rush, Brother Dominic, are not done with godliness of thought. Impetuosity should be constrained and—’

‘Forgive me, Father, but …’ The young man interrupted, his voice rather higher than usual in his excitement. ‘Walter the Steward is dead.’

‘That is assuredly unfortunate news, but death comes to us all, Brother, and is no cause for—’

‘Dead by,’ and the monk’s voice now dropped, ‘a terrible accident, Father. Prior Richard sent me to tell you immediately.’

‘I see. Well, you have told me, and now you will compose yourself.’ Abbot Reginald’s voice was as calm as if he had been told that the weather was set fair for the day. It would not do, he thought, to show a poor example. ‘We shall walk together to Prior Richard and hear exactly what has occurred.’

‘Yes, Father.’ Brother Dominic, gently chastised, coloured, and then folded his hands beneath his scapular, emulating his superior.

Prior Richard was in the courtyard by the western and primary gate of the abbey enclave, and with him were several men and a handcart bearing a covered body. The men were all trying to speak at once, and there was much gesticulating. The noise only ceased when Abbot Reginald himself was close enough to ask for calm.

‘I am told our steward is dead. Who found him, and where?’

‘I – we did, my lord Abbot, when we went to begin our labours for the day.’ A short, broad-shouldered man, stepped forward and bowed.

‘And you are?’

‘Adam the Welldelver, my lord. And this is—’

‘Hubert the Mason. Your face I know. So you found Walter the Steward on the green, where the well is being dug?’

‘Not just on the green, but in my workings, though blind drunk ’e must have been to fall in when the soil hoist is all set up above it.’

‘How deep have you dug thus far?’

‘A good fifteen or sixteen feet, and a fall that far could kill a man.’

‘Yes.’ Abbot Reginald seemed to be only half attending, and a small frown gathered between his fine brows. ‘Uncover the body.’

Hubert the Mason leant over the side of the cart, pulled back the cloth, and then crossed himself. Walter the Steward lay slightly contorted, facing to his left side, since nobody had wanted to move his death-stiff limbs, nor force the eyelids closed. The sightless stare unnerved Brother Dominic, who took an audible breath, and Abbot Reginald’s frown deepened. Something jarred. One arm was clearly beneath the body and the other lay, almost casually, to the side. It would be odd for a man, even a drunken man, not to put his arms out if he tripped and fell. The side of the face that was visible bore little sign of injury, but there was a very distinct wound to the left temple, with congealed blood about it. The thin bone of the skull could be seen, like the broken shell of a goose egg.

‘He was found just like this?’ Abbot Reginald looked...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Bradecote & Catchpoll |

| Bradecote & Catchpoll | |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Historische Kriminalromane | |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Schlagworte | 12th century • Bradecote and Catchpoll • Crime • historical crime • Medieval • Murder • Mystery • Sarah Hawkswood • Worcester • Worcestershire |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7490-3103-4 / 0749031034 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7490-3103-9 / 9780749031039 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 490 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich