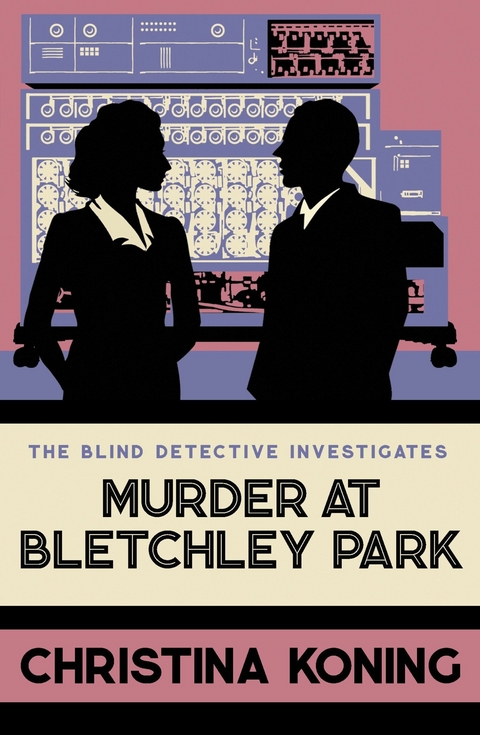

Murder at Bletchley Park (eBook)

350 Seiten

Allison & Busby (Verlag)

978-0-7490-3063-6 (ISBN)

Christina Koning has worked as a journalist, reviewing fiction for The Times, and has taught Creative Writing at the University of Oxford and Birkbeck, University of London. From 2013 to 2015, she was Royal Literary Fund Fellow at Newnham College, Cambridge. She won the Encore Prize in 1999 and was long-listed for the Orange Prize in the same year.

Christina Koning has worked as a journalist, reviewing fiction for The Times, and has taught Creative Writing at the University of Oxford and Birkbeck, University of London. From 2013 to 2015, she was Royal Literary Fund Fellow at Newnham College, Cambridge. She won the Encore Prize in 1999 and was long-listed for the Orange Prize in the same year.

Cambridge was utterly silent and, he knew, as dark as it was quiet – the one condition, which was the blackout, bringing about the other. Not that the darkness made much difference to Frederick Rowlands. But it had certainly cast a spell upon the streets of this university town, as it had upon those of the capital, from which he had travelled earlier that day. There, the blackout had the effect of making sounds seem louder, as they did in thick fog, so that the roar of a motorbus or the clip-clopping of a rag-and-bone man’s horse seemed to come at you unmuffled by other sounds, such as the tramp of feet, or the murmur of a rush-hour crowd. Because, after three months of continuous night-time bombing, London’s streets were starting to get the deserted feel Rowlands recalled from the last war. It wasn’t quite the feeling that a curfew had been imposed (it hadn’t – or not officially), more that, if you didn’t have anywhere particular to go, you oughtn’t to be out. New sounds had also been added to the more familiar ones of traffic and people’s voices. The icy tinkle of broken glass, being swept up after a night’s raid; the sudden crash, as a building collapsed. The smell of the city had changed, too: now a smoky fog composed of brick dust and smashed plaster hung in the air, sometimes overlaid with fouler smells, of broken drains, and dank cellars full of rotting things, now exposed to view.

‘I think we must be nearly there,’ said his companion, breaking into these thoughts. Margaret sounded as if she didn’t quite believe this, however. After she’d met his train at the station, the two of them had agreed that it would be quicker to walk into the town centre, rather than to wait for a bus, which was likely to be crowded with home-going workers at this time of day. So, having turned out of Station Road, they’d set off down Hills Road and thence along Regent Street and St Andrew’s Street – not in itself a great distance, but it was funny how much further it seemed in the dark, said Rowlands’s daughter, adding, with a little laugh, that it was a good thing he’d only brought an overnight bag.

They turned at last along Downing Street, and reached the turning into Free School Lane.

‘It’s just down here to the left,’ said Rowlands. ‘If memory serves.’ Which, in his case, it usually did – memory having to stand in for the sense of sight. Not that it would be of much help in this pitch blackness, he supposed, if one could see. Through the darkness to their left, he knew, loomed the magnificent late Perpendicular Gothic edifice of King’s College Chapel – built by a succession of Tudor kings and eventually completed by the notorious wife-killer, for the glory of his immortal soul. Rowlands’s visual memories of the chapel, and indeed of Cambridge as a whole, went back to before the last war, when he’d come here as a representative of the publishing firm for which he’d worked at the time. He remembered wandering around the great building, marvelling at the splendours of its sixteenth-century fan-vaulting and Flemish stained glass, in the half-hour before his meeting at Heffers Bookshop in Petty Cury.

‘Here we are,’ he said, as they reached the junction with Bene’t Street. ‘I remember the cobblestones.’ These belonged to the courtyard of the Eagle – that well-known Cambridge hostelry, beloved of many generations of undergraduates. It was several years since Rowlands had last visited it, in the company of his old friend, the artist Percy Loveless. When last heard of, Loveless was in Canada – stranded there for the duration – having arrived in that country just before the outbreak of hostilities, in order to carry out a portrait commission. ‘This place is as cold as the ninth circle of Hell,’ he had written, with uncharacteristic gloom. ‘If anywhere could make me long for the dreary reaches of Notting Hill, then Toronto in midwinter is that place …’

Even if the feel of cobblestones underfoot hadn’t alerted Rowlands to the fact that they’d reached their destination, the sound of voices would have done so: it was only just past opening time, and yet the pub was already filling up with its regular clientele of rowdy students, glad to have finished with lectures for the day, as well as some older men – whether dons or college porters wasn’t always easy to determine – also taking a break from their labours.

‘What’ll you have?’ said Rowlands to his daughter as they reached the bar. ‘A nice glass of sherry?’

‘Daddy!’

‘Isn’t that what you university types usually drink?’ he said innocently.

‘No, thanks,’ was the reply. ‘I’ll have half a bitter, please.’

‘Right you are.’ He gave the order, and exchanged a few pleasantries with the barmaid – a friendly soul, hailed by all and sundry as Doris. ‘Busy tonight,’ said Rowlands, for something to say, as the young woman filled their glasses at the taps.

‘Oh, it’ll be busier still tonight, with all the RAF boys coming in,’ she replied, in the soft accent of the region.

‘I say, Doris my love, hurry up and get us some beers, will you?’ said a bold young man, standing behind Rowlands.

‘You mind your manners,’ said Doris, then to Rowlands: ‘That’ll be one-and-ninepence, sir, if you please.’

Rowlands paid her, and then he and Margaret carried their glasses over to a table in the corner of the back bar, which was quieter than the rest of the pub.

‘So,’ he said, having taken an appreciative draught of his pint. ‘What’s all this about your giving up your studies?’

Margaret didn’t say anything for a moment. Her father got the impression she was choosing her words carefully. ‘I’ve told you – I’m simply deferring my research until the war’s over. Lots of people are doing it.’

‘I suppose you’ll be telling me next that you want to join up?’ he said.

Again, there was a slight hesitation before she replied, ‘Not exactly.’

‘Then what are you intending to do?’ He kept his voice level, but really it was exasperating – his brilliant daughter, who’d delighted them all by winning a scholarship to Cambridge to study mathematics, and then had achieved further distinction after graduation by being offered a junior research fellowship, was now proposing to give it all up, to do … what? He took another pull of his beer.

‘I … I can’t tell you,’ said Margaret.

‘But surely,’ he persisted, ‘research was what you wanted to do? Or have you changed your mind?’

‘No … it’s not that. I still want to do it – more than anything else in the world. It’s just that I’m going to have to defer it until the war’s over … Oh, don’t ask me to explain!’ she cried suddenly, sounding so miserable that Rowlands instantly resolved to drop his inquisitorial tone.

‘It’s all right,’ he said. ‘Let’s talk about something else … How’s that young man of yours, these days?’

‘No, that’s not fair,’ she said, lowering her voice – although as far as Rowlands could tell, there was nobody sitting close enough to overhear. ‘You deserve an explanation. At least,’ she added, ‘as far as I can give one. I’ve been offered a job. In … in a government department. But that’s all I can say, I’m afraid.’

‘All very hush-hush, eh?’ said her father. ‘“Careless talk costs lives” and so forth?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then you needn’t say another thing. I’ll tell your mother she’s not to ask you any more questions, either.’

‘Thanks, Daddy.’ The relief in her voice was all too apparent. ‘And he’s not my “young man”, as you call him,’ she added, in a lighter tone. ‘We’re just friends. Why, Jonty’s almost like a brother.’

Rowlands wondered if Jonathan Simkins, the son of family friends, felt the same. Wisely, he said nothing.

‘As a matter of fact, he’s joining the RAF,’ Margaret went on. ‘His engineering course at Durham has finished, anyway, and so he’s decided to waste no more time.’

‘Very public-spirited of him,’ said Rowlands, although his heart sank at the thought of all these young men and women who were so eager to join the war effort. Memories of his own youth, and the way he and his Pals had rushed to join up in 1914, to fight for what they believed was a noble cause, could not but cast a long shadow. He shrugged away the thought. ‘So I take it,’ he said, picking up the thread of an earlier conversation, ‘that you’d rather your mother and I didn’t come and meet you at the end of term?’

‘Yes,’ said...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.12.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Blind Detective | Blind Detective |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Historische Kriminalromane |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Schlagworte | amateur sleuth • Bletchley Park • Blind Detective • Christina Koning • Crime • Crime Fiction • detective • Fred Rowlands • Interwar • Murder • Mystery • sleuth |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7490-3063-1 / 0749030631 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7490-3063-6 / 9780749030636 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 330 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich