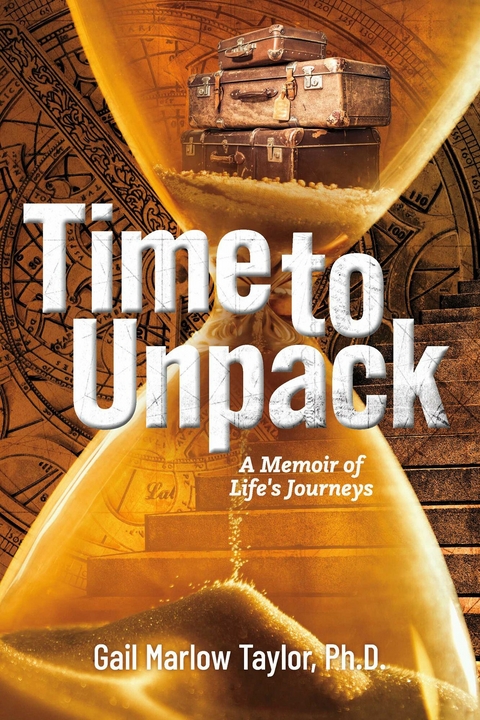

Time to Unpack (eBook)

332 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-9054-8 (ISBN)

Gail Marlow Taylor's childhood in Tehran and Geneva inspired her with a lifelong passion for travel. "e;Time to Unpack is a memoir about growing up as a restless traveler, who always felt most at home when on the move. It all started in the 1950's, when Gail's father was asked to establish a school of public administration at the University of Tehran. Like thousands of Americans, her family moved to a faraway land during the Cold War as part of a foreign aid project. This is a story about a little girl growing up in Iran and Switzerland, a teenager adjusting to life in America, newlyweds rejected by the Peace Corps, a woman balancing family and career, and a retiree going for a Ph.D. It tells of travel to places like Morocco and Tunisia and living in Japan and Germany. But more than a tale of faraway places, this is a journey through time, from the 1950s to the Pandemic of 2020.

Chapter 1.

A Wish to Be Settled

People wish to be settled; only as far as they are unsettled is there any hope for them. —Ralph Waldo Emerson

California attracts unsettled people. Our family stories tell of leaving England, Ireland, and the religious turmoil of the German Palatinate and heading for the colonies of Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, and Georgia. Some stayed where they landed. But in each generation some children moved on. After the Civil War, the opening of the Transcontinental Railway just made it easier. From the North, the Marlows and Scribners traveled through Ohio and Iowa to Nebraska, while the Brewsters and the Fulbrights left homes in Mississippi and Arkansas seeking fertile farmland in Missouri. My parents, Harry Marlow and Virginia Brewster, were the offspring of restless Midwesterners. They grew up, met, and married in California because two women decided to take the westbound train.

Virginia’s mother, Addie Fulbright, left Missouri in 1910 at the age of nineteen because her sister had found a job for her in San Bernardino. Ten years later Harry’s mother, Lottie Marlow, left husband and home in Nebraska to bring four children to Los Angeles on the Santa Fe. Although Addie and Lottie would never meet, their lifelines would merge in 1944 when Addie’s oldest daughter, Virginia, married Lottie’s youngest son, Harry.

Addie, My Mother’s Mother

Life was going well for Addie after business college, and she had no plans to move west. Her parents were both born in Missouri of families who came from the South. Addie’s mother, Mary Ellen McShane, told the children how her own mother was only seven when she saw her father shot by a Union soldier on the front porch of their home in Arkansas. Addie’s uncles recreated Civil War battles at family dinners, moving salt cellars, spoons, and butter knives around the table to show how the strategy could have played out.

Addie Fulbright, Business School Graduation, 1910

But to Addie, the war was ancient history. The twelfth of thirteen children, she had been too young to go with her sisters to the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Now, as a business school graduate, she couldn’t wait to leave the family farm in Dry Glaize, Missouri. But she didn’t go far. Addie boarded with a family in the nearby town of Dixon where she took a job in the general store. She loved living in a town where there was always something going on. She was so excited one summer morning in 1910 when they all ran outside in their dressing gowns to see Halley’s Comet, “like a long silver kite slanting down the sky.”3 Enjoying her newfound freedom, she made friends, went to parties, and played a fair game of croquet. “I was settling down real cozy there and liking it,” she wrote.4 Then came a letter from her sister Ruby offering her a job in San Bernardino.

Ruby was the daring older sister with a flair for clothes. She assembled each outfit meticulously, even dyeing her shoes to match her dresses. On her last visit to the Missouri farm, Ruby stayed home just long enough to flaunt an engagement ring and then took her sister Lucy back east to see Niagara Falls and New York City before getting married in California. By this time, several of her brothers had moved to California as well. Although Addie didn’t think that being a cashier in a restaurant quite measured up to the kind of job she had prepared for in business college, she jumped at the chance to join her siblings out west.

She decided to take the six-day scenic route on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, going through the Royal Gorge in Colorado, then through Salt Lake City and down the coast. Whenever she was hungry, she would jump off the train at the next stop and run into a restaurant to grab a snack—“sandwich—fruit—candy bars, etc.” she noted later—and then run back to hop on the train. Although she made friends with the boy who sold newspapers to the passengers, Addie was naturally cautious and avoided conversations with strangers.

She saved her best outfit, a yellow blouse and a long black skirt, for her first day’s work at a new self-service cafeteria near the Santa Fe railroad station in San Bernardino. On a warm Sunday morning, Addie leaned forward attentively at the reception desk while Ruby showed her how the new cash register worked. Then a neatly dressed young man stopped in for lunch after church and looked right at her. He thought she was the prettiest girl he had ever seen.

Clifford, My Mother’s Father

While Addie was growing up on the farm in Dry Glaize, Clifford’s family was always on the move. His father, Asbury Brewster, a Mississippi doctor, had married Aurelia Cook at Fort Smith, Arkansas in 1889. Clifford, the oldest of eight children, and his brother Houston were born in Huntington, Arkansas, where Asbury practiced medicine. But when Asbury was offered the post of resident doctor for the Sacred Heart Mission in the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, the family loaded up a covered wagon and headed west. Although the Brewsters remained Methodist, Clifford received his early education at the Catholic mission school.

It was a good thing that her husband was an obstetrician, because Aurelia soon gave birth to two more boys and a girl at the mission, followed by the twins, Pearl and Earl. Raising seven children at the rugged frontier mission proved a hard life for Aurelia, however. With a husband who was frequently called away, the weariness and sheer loneliness weighed her down. Hoping that California’s mild climate would improve her health and spirits, the family moved to San Bernardino in 1906, only a year before the Oklahoma Territory became a state.

Clifford was sixteen by the time the family moved to California, old enough to work in his father’s pharmacy while he was in high school. He was a good student and earned a scholarship to Longmire Business College in San Bernardino, taking his courses at the same time as Addie was in business college in Missouri.

And Aurelia, his mother? After giving birth to Eva, her eighth child, Aurelia enjoyed excellent health, outliving her husband by thirty-one years. Much later, Mother took my brother Billy and me to see our great-grandmother in 1956, when we were on home leave from Iran. I was fascinated by her tiny cottage in Long Beach, where she lived right behind her granddaughter Lorraine. Great-Grandma’s face bore the lines of time but lit up with a smile when she saw us. “Come closer so I can see your faces!” Her voice was soft, yet firm. “It’s hard when your eyes go,” she added. “Not much point in living if you can’t even read.”

She died two years later at the age of eighty-nine.

Addie and Clifford, My Mother’s Parents

When Addie first saw Clifford Brewster enter the cafeteria on that hot August afternoon in San Bernardino, they were both nineteen and had much in common. Even their birthdays were close together. He would turn twenty on October 1, 1910, only two weeks before she did. They had both attended business college after finishing high school. They were both members of the Methodist Church. And both came from large sociable families transplanted from the Midwest: the Fulbrights of Redlands and the Brewsters of San Bernardino. Clifford continued to work for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad three more years while he visited Addie every Sunday afternoon and saved up for a house. They were both twenty-two when they were married in the Redlands Methodist Church—one year younger than Yosemite National Park, where they spent their honeymoon.

Clifford and Addie on their wedding day, Redlands, 1913

A few years later, Clifford was offered a job as a bookkeeper in Flagstaff, Arizona. There, Addie gave birth to their first child, a boy. To their lasting grief, the baby died the same day.

After the United States entered World War I and the draft took effect, Clifford enlisted in the Navy and was assigned to the Naval Station in Long Beach. As the war ended, the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 hit Long Beach. Addie wrote, “Flu struck hard that winter, taking thousands of lives.” The hospitals were full, so most people quarantined at home when they were sick, as did Addie herself.

After the war, Clifford applied for clerical work with the Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company. His timing was perfect. In 1921, Shell Oil drilled the Alamitos oil well on Signal Hill in Long Beach, opening up one of the richest oil fields in the world. Clifford had steady employment with the company until 1935, all the way through the Depression. The couple had two more children, Virginia and Betty, both born at Seaside Hospital in Long Beach. But our connection with the hospital didn’t stop there. In 1960, Seaside Hospital became Memorial Hospital of Long Beach, the place where I started my medical technology training in 1969, while my husband Chuck was stationed at the Naval Station in Long Beach as my grandfather had been before him.

Addie and Clifford celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1965. By that time, they had survived two world wars and the Great Depression and seen both daughters graduate from the University of Redlands, marry, and have families of their own. To me they were the grandparents who always welcomed us with big smiles and open arms. Addie and Clifford are the grandparents I was privileged to know.

Lottie and William,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.4.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-9054-9 / 1667890549 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-9054-8 / 9781667890548 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich