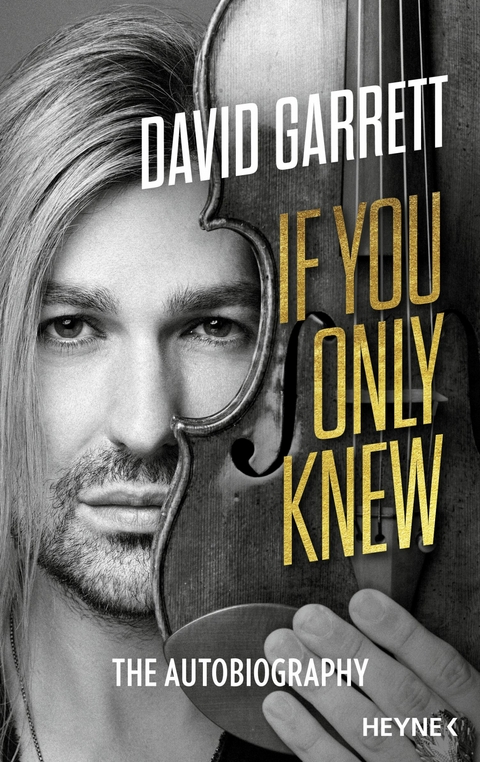

If You Only Knew (eBook)

368 Seiten

Heyne (Verlag)

978-3-641-30699-1 (ISBN)

The road to the pinnacle of violin-playing has not been an easy one for David Garrett. His childhood revolved around discipline and working daily with his father, who fostered his talent and supported him, while also being an ambitious driving force. From the tender age of ten, he was already performing on stage with the world's greatest orchestras, later playing all the classical works as a teenager, before freeing himself from the shackles of his wunderkind existence in his early twenties and moving to New York to study.

It was in that city that he laid the foundations for a new genre of classical music in the form of 'crossover', combining virtuoso violin music with the latest pop, which made him more famous than ever before. David is the perfect embodiment of a young man's onerous quest to carve out his own path and live authentically, finding his very own solution to this problem by fully committing to something that could just as easily have destroyed him as a person - music.

In this autobiography, we witness his world through his own eyes; the dazzling highs, along with the sweat and tears - a dramatic, inspiring and touching book for all fans and music-lovers.

Im Alter von 4 Jahren werden das Interesse und die Leidenschaft von David Garrett für die Violine geweckt, und er bekommt den ersten Unterricht. Mit 10 Jahren gibt er sein Orchester-Debüt, mit 13 Jahren wird er der jüngste Künstler, der jemals bei der Deutschen Grammophon unter Vertrag genommen wurde. Er spielt als Solist die großen Violinkonzerte mit den führenden Dirigenten und Orchestern der Welt.

Eine schwere persönliche Krise bringt ihn dazu, mit Anfang 20 ein Studium an der weltberühmten Juilliard School in New York zu beginnen. Hier perfektioniert er seine Idee von »Crossover«-Musik, indem er Melodien der Klassik auf seine ganz eigene Art und Weise mit Rock- und Pop-Elementen verbindet. Mit dieser Kombination schafft er es, Menschen generationsübergreifend für klassische Musik zu begeistern. Für den großen Erfolg stehen beispielhaft über 1600 Konzerte weltweit, über 4,5 Millionen verkaufte Alben sowie 25 Gold- und 17 Platin-Auszeichnungen u. a. in Deutschland, Österreich, Hongkong, Singapur, Taiwan, Mexiko und Brasilien.

This impossible instrument

With my father, on one of the first times I ever tried playing the violin

Do I really remember it? Or am I simply recalling the memories of others? I think I do remember ... Szeryng was going to perform in Aachen in 1985. Polish-born Henryk Szeryng, one of the greatest violinists of his time – and I would soon be able to see and hear this hugely acclaimed man in my hometown. Incredible! Being just four years old, of course I had no idea how lucky we were, but my father was adamant that we should go. So we bought our tickets, quite near the front, to be as close as possible to this Henryk Szeryng. But one thing first had to be clarified: should we take our youngest child with us? Will he be able to sit still for so long? Will he whine? My father made the executive decision: ‘David is coming. He needs to listen to this.’ Worst-case scenario, my mother would have to take me out of the auditorium.

That night, I sat between my parents in the fourth row of the Eurogress concert hall, and, as Szeryng played, I started imitating the violinist I was watching up on stage – playing air violin, so to speak. I guess it must have looked pretty weird. Szeryng certainly noticed there was a child down there playing along, and, in the breaks between pieces, he would look at me and actually wait until I had calmed down again and was sitting still before nodding at the pianist and continuing to play.

After the concert, he came back on stage to play an encore. That’s pretty standard. But what happened then, wasn’t at all. As the applause died down, he stepped to the front of the stage, pointed his bow at me and said, ‘When I was the same age as this little boy in the fourth row, I listened to Fritz Kreisler in concert.’ Kreisler was a violinist from the 1920s and ’30s, of the same calibre as Szeryng. ‘Kreisler’, he continued, ‘saw me in the audience and dedicated his encore to me at the end, namely Tempo di Minuetto, which he had composed himself. And tonight’ – he looked at me again – ‘I am playing Tempo di Minuetto by Fritz Kreisler for you, young man.’ This Tempo di Minuetto is a heartbreakingly romantic piece, a sweet little lullaby for a little prince, and he played it for me. Perhaps this moment was the initial spark. In any case, it wasn’t long before my father pressed my first violin, a little child’s violin, into my hands.

The violin is a curious instrument. Maybe this is something I should save for later, but then again I absolutely have to talk about it now, because – what would I be without my violin? I have asked myself this question again and again throughout my life, trying to imagine a life without a violin, and I haven’t been able to, because I’m violin-obsessed. I just love violins; they have an irresistible allure for me, and not only because of the music – it’s the violin itself that has me hooked, because I have experienced too much with it; the awful and the amazing. And anyone wanting to understand me needs to understand this instrument before embarking on my life journey with me. So for anyone who has never played a violin, I want to briefly explain what makes it different from other musical instruments.

If you want to make music, there are basically four different ways of creating sounds (leaving aside the human voice for the moment). You can press air through holes, in which case the sound is determined by keeping some holes shut and others open – that’s how flutes, trumpets, clarinets and organs work. That’s method #1. Or you can strike an object, whether with your fingers or with sticks or mallets – this is the case for pianos, drums, triangles and xylophones, and it’s method #2. Then you can get strings to vibrate by plucking them, such as with guitars or harps. That’s method #3.

Bowed instruments such as the violin and cello add a fourth option to this repertoire. It can be described as rubbing/friction, scraping or scratching, and doesn’t really sound like a promising way of producing melodious sounds. As the word ‘scratching’ implies, this method can produce sounds, but very rarely are they nice ones, and so begins the torment of the young violin student.

There is probably no worse instrument for a beginner or, in fact, anyone living with or near them. Learning to play the violin requires nerves of steel from everyone involved. Even my father’s nerves must have been shot after a while. And we haven’t yet even spoken about the actual problem, namely intonation – that is, the process of actually finding the right note on your violin.

Let’s compare it with the piano. Provided the instrument has been properly tuned, I only need to press down on a piano key to promptly get the note I want, pure and undistorted. Any small child can be taught to play a clean C-major chord on a piano within seconds. Achieving the same on a violin takes months. Why? Because a piano serves you every note on a silver platter; you have a keyboard about two metres long, with keys on top that are so wide it’s hard to miss them even during an allegro furioso. On a violin, however, the notes are not defined. You can’t see them with the naked eye; you have to find them blindly. It’s a case of millimetres, even micro-millimetres, often within milliseconds! Instead of a two-metre-long keyboard, you have only a short fingerboard that packs in the entire range of notes over a few centimetres, meaning that the individual notes are all tightly crammed in next to each other. It is a mystery how, given these conditions, and often at lightning speed, anyone is ever able to hit a clear, sharp and clean-sounding note.

As if that weren’t enough, when you have hit the note, you still haven’t actually produced it. No sound comes out, because there is no friction. It is only once the bow is used that the violin comes to life, which brings you to your next problem, namely that of having to perform movements with your right hand that are completely different to what the left hand is doing. Your left hand is feeling its way along the strings more or less nimbly, while the right is performing upward and downward motions – at a completely different pace – with a bow. Well, now try coordinating these two movements! Not to mention the fact that, using this bow, you have to pinpoint the ideal spot between the bridge and fingerboard; in other words, that section of the string that gives you a smooth, round sound. You have to find this exact ideal point for every single note, and if you’re looking for it in the same section of the upper string as it is on the lower string, you would be wrong – it’s in a different place at the top.

To cap it all off – and this is where I will leave things for the moment – no physiotherapist would ever have invented such an instrument. Pianists have to be a bit careful of their backs, it’s true, but a violinist needs to expect leg and back twinges after two hours, because they are forced to contort their bodies. After all, the violin needs to be held somehow, so you’re standing there with your head turned to the left, the left shoulder slightly raised and the instrument clamped between your shoulder and chin. While the left hand offers a little support, it is also needed for acrobatic finger movements and therefore needs to be able to move freely, so holding the violin from this side is out of the question. What this means is that, on top of all the technical challenges associated with playing the violin, the body and violin also need to work together perfectly.

In short, it is a nearly impossible instrument. The degree of difficulty is brutal, and the prospect of becoming an elite violin player as likely as scaling Mount Everest alone without oxygen. So now comes the totally justified question: why would anyone encourage helpless little four- or five-year-olds to take on the struggles associated with this instrument?

The answer is: because experience has shown that, at later ages, the head and hands are no longer up to the task of handling the violin’s tremendous demands. Someone who starts at age ten or twelve won’t necessarily be a bad violinist, but they will never reach the summit of Mount Everest. Perfectly hitting a string with a finger of the left hand with millimetre precision is a fine-motor feat that can only be learned very young, and it’s a similar story for developing a skilled ‘ear’. Not even the best concert violinist in the world can hit every note exactly right one hundred per cent of the time. They will constantly have to make corrections within a fraction of a second, and these tiniest of corrections require an extremely precise ear trained all the way from childhood. So it’s better to start when the brain is still able to absorb everything like a sponge, when every grip can still be imprinted into the subconscious. My father was right in this respect. No brilliant violinist, no world-famous pianist began playing their instrument as late as the age of eight or nine, and my father was probably envisioning an international career for me very early on.

For the time being, however, little David is standing in the living room of his parents’ house in Aachen, grating away on his Suzuki fibreboard violin, making noises that, even to him, sound horrendous. For now, he has to learn to live with something that is torture for his ears. Thank God I can’t remember my earliest beginner days. I can imagine the strain it puts on the nerves of everyone involved when I hear young people who are just starting out. It’s so much more enjoyable when someone is learning to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.12.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Schlagworte | 2022 • Ada Brodie Bruder • Alive • Anne-Sophie Mutter • attractive • Biografie • Biographien • Christian Bongartz • Classical music • Coldplay Geige • Coldplay Violin • Crossover • Deutsche Grammophon • eBooks • Elena Bruder • englische Bücher • Fashion Design • flight of the bumblebee • garret • Geigenpop • Geiger Biografie • Guadagnini • Guarneri del Gesu • handsome man • Itzhak Perlman • Klassik • Klassikpop • Kunst • Lange Haare Geige • Long hair violin • Musician hot • Musik • Neuerscheinung • Paganini • Popklassik • Rock Symphonies • Sexy • Stradivari • Teufelsgeiger • UNESCO Ambassador • UNESCO-Botschafter • Viola • violin • Violine • Violinist • Violinist Biography • Violinist hot • Viva La Vida Geige • viva la vida violin • world records • Yehudi Menuhin • Zubin Mehta |

| ISBN-10 | 3-641-30699-X / 364130699X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-641-30699-1 / 9783641306991 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 25,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich