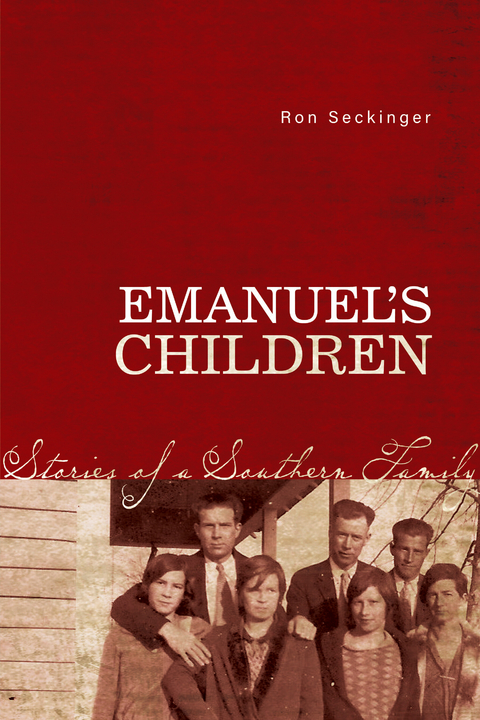

Emanuel's Children (eBook)

392 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-0983-6840-1 (ISBN)

Ordinary people, extraordinary lives. These are true stories of the Strouds, eight siblings born into rural poverty in Emanuel County, Georgia at the turn of the 20th century. Surviving a childhood of hard work, deprivation, and sparse expectations, they followed different paths in their separate quests for security or survival. None occupied a high public office, amassed a fortune, starred in movies, or discovered the cure for a disease. They occasionally crossed paths with the famous but rarely attracted attention beyond their small circles of family, friends, and acquaintances. Yet drama filled their lives. Most of them knew squalor or tragedy or both. Some displayed incomparable strength of character and achieved modest triumphs under exceptionally trying circumstances. Others surrendered to alcoholism or despair. Their combined experiences included death in childbirth, murder, the loss of an only child, suicide, railroad strikes, sharecropping, the revival of Ku Klux Klan, migration to jobs in Northern factories, the settlement of Southern Florida, the hurricane of 1928, work for the Tennessee Valley Authority, and building Liberty Ships. As the collective memory of a generation is lost, these stories pay homage to ordinary but complex men and women who demonstrated courage daily and who usually, but not always, remained true to their better natures. To know their lives is to understand an essential part of the great changes that have transformed the South and the nation. "e;There's no finer memorial to one's kinfolk than an account of their lives that people with no connection to them can read with pleasure and profit. The Strouds are an interesting bunch, and Seckinger makes the most of that. Moreover, situating them in their time and place casts light on the dramatic social and economic changes that swept over the twentieth-century South. Seckinger handles a large cast of characters adroitly and his prose is a delight to read."e; -- John Shelton Reed, author of 1001 Things Everyone Should Know about the South

TOWN AND COUNTY

BY 1910, EMANUEL County claimed some 25,000 persons, up from 6,000 in 1870. During the same 40 years, annual cotton production had soared from fewer than 1,400 bales to more than 59,000. Most people still worked the soil or cut timber, relying exclusively on human and animal power. The population covered the landscape, and more than a dozen thriving communities catered to the needs of families in the surrounding areas.

Stillmore, for example, located at the intersection of two rail lines, had large machine shops where “anything can be done to a locomotive except to manufacture it.” Adrian, divided by the boundary that separated Emanuel and Johnson Counties, boasted its own newspaper, hotel, cotton gin, saw and shingle mill, turpentine still, and an assortment of general stores, millineries, and groceries. A factory in Garfield produced cottonseed oil, and entrepreneurs exploited Emanuel’s pine forests at sawmills, turpentine stills, crosstie businesses, and naval stores concerns in Aline, Blun, Blundale, Covena, Dellwood, Gertman, McLeod, Modoc, Nunez, Oak Park, Rackley, Summertown, Summit, Von, and Wade. Huge mounds of sawdust dotted the county, a hazard to unwary children who jumped on them despite their parents’ warnings. Other communities included Kemp, Norristown, Lexsy, Graymont, Maceo, Merritt, and Nell. A few had banks, and many had druggists, liveries, blacksmiths, dry goods stores, and other establishments.

With some 1,300 souls, and as the county seat, Swainsboro was the largest and most prosperous community, although the Forest-Blade surely exaggerated when it declared in 1910 that “the magic touch of Southern enterprise has stripped her of her swaddling clothes and developed her into one of Wiregrass Georgia’s fairest debutantes–-a belle among cities.” The same newspaper had complained six years earlier that Swainsboro would need two marshals and a dog to keep hogs and cows off the streets. And, in the absence of a city water works, outdoor privies studded backyards throughout the town.

Gentry Brothers’ Circus was one of many attractions available to Swainsboro residents at the turn of the 20th century.

Still, improvements kept coming. In 1904, Swainsboro gained an electric light plant and a new school building for White children with a 1,000-seat auditorium. In 1918, Black children obtained their own school building, constructed not by the city or county but by Julius Rosenwald, philanthropist and founder of Sears Roebuck. The Rosenwald Foundation provided matching funds to build 5,300 schools for Black children in the South and Southwest between 1917 and 1932.

In 1906, the Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company established telephone service for 73 customers in Swainsboro. An operator known as “Central” connected callers and located doctors if needed. Central would even contact other operators to investigate weather and road conditions for a subscriber planning a trip.

An ice factory appeared the same year, and by 1910 the town claimed 12 general stores, two druggists, a photographer’s studio, five grocers, a butcher, a hotel, two blacksmiths, two livery stables, a hardware-furniture store, two jewelers, a turpentine still, a sawmill, a planing mill, a naval stores company, a Coca-Cola bottling plant, and two banks-–which between them had a total capitalization of $70,400.

Brick buildings began to replace wooden ones along the courthouse square. Several physicians practiced locally, and a dentist and an optician from other counties visited periodically–-usually during Superior Court session, when they could count on finding many farmers in town. Residential neighborhoods mushroomed as new thoroughfares pushed out from the center. By 1911, local women had founded the Civic Improvement Club to clean up the streets, cemeteries, and other public spaces.

When not beautifying the town, citizens could choose from a growing list of leisure activities. In 1907 a druggist inaugurated a roller-skating rink above his store on Main Street, and the sport quickly became a fad among young people. Baseball games marked summer afternoons; Swainsboro had two teams for Whites and one for Blacks, and practically every other community had at least one team for each race. Men could participate in the activities of various lodges and secret societies, including the Masons, the Odd Fellows, and the Knights of Pythias. Nearly every year, Confederate veterans held a camp meeting to reminisce about the war and bask in the adulation of their fellow citizens. Some families owned pianos–-a tuner periodically visited from Augusta-–and even a few “talking machines” or phonographs.

Performances by traveling artists, who had long enlivened the boredom of backwoods communities and tempted children to run away from home, became more frequent with the expansion of the railroads.

From the appearance of the first posters, all of Swainsboro buzzed with anticipation. During a 14-month stretch in 1909-1910, the town hosted the Gentry Brothers’ Circus, the Mighty Haag Railroad Shows-–featuring a somersaulting elephant—the K.G. Barkoot Carnival Company, Howe’s Great London Shows, and John H. Sparks’ World Famous Shows. Medicine shows, films, and vaudeville acts rolled into town. Opera houses presented a variety of entertainments, such as the 1904 performance of the melodrama “Only a Woman’s Heart”–-prices 25, 35, and 50 cents.

African Americans watched these spectacles from separate seating areas. Numbering nearly 10,000 in 1910, Blacks accounted for two of every five residents of Emanuel County but shared little in the new prosperity. Only 162 African American families owned their own farms, while 941 worked as tenants. Almost half of all Black males of voting age couldn’t read, according to the federal census of 1910, compared to 12 percent of White males.

Not that Blacks were allowed to vote. The turn of the century witnessed the enactment of Jim Crow laws that segregated and disenfranchised African Americans throughout the South. Georgia voters had paid poll taxes since 1877, and in 1892, the Democratic Party began staging Whites-only primaries to select candidates for general elections. Emanuel County held its first in 1904. In 1907, Governor Hoke Smith, elected the previous year on a platform calling for Black disenfranchisement, secured a state constitutional amendment stipulating that each registrant meet one of five requirements, such as pass a literacy test or pay the poll tax six months before the election.

In daily interactions. Whites and Blacks often maintained an easy familiarity. But the descendants of slaves knew where they stood. The Forest-Blade–-like Hoke Smith’s newspaper, the Atlanta Journal-–poked fun at Blacks, patronized those whose behavior it considered exemplary, and expressed outrage at the real and imagined depredations of others.

African American women wash chitterlings during a hog-killing day in Emanuel County, date unknown. Courtesy, Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia Collection, emno382.

Frequent acts of violence buttressed White supremacy. Georgia’s 505 recorded lynchings led the nation during the period 1882-1923, and the number rose annually while remaining steady or declining in most other states. Moreover, the violence extended to every region of Georgia. By 1930 lynchings had occurred in 119 of the state’s 159 counties. In 1906 alone, Georgian vigilantes murdered 73 persons, all but three of them Blacks.

One of the victims, a young man named Ed Pierson, met his death at the hands of an Emanuel County mob. Masked men seized Pierson, allegedly discovered under the bed of a White woman, during his transfer from the Swainsboro jail to Savannah, and the murderers dumped his bullet-riddled body in the Canoochee River.

Poor Whites like the Strouds had much in common with poor Blacks, but the efforts of Populist leaders like Tom Watson in the 1890s to forge a biracial coalition dedicated to achieving political power and enacting policies favorable to Southern farmers had come to naught. White supremacy prevailed, and even those Whites uninfected by blind hatred generally assumed their own superiority and expected deference from Blacks.

Beneath the fabric of Whites’ daily life lay a propensity for violence, visited not only on African Americans but also on other Whites. Every rural family had hunting weapons, and many men carried pistols. Locals often settled disputes, particularly those initiated under the influence of alcohol, with guns.

For example, a feud between Tom Moxley and Jim Stroud’s older brother John culminated in a shootout in 1901. Moxley, John Stroud’s nephew and brother-in-law, had threatened, cursed, and libeled his relative, according to the Swainsboro Pine Forest. When the two men met on a public road and exchanged words, Moxley reportedly pulled a revolver and took two shots at Stroud, who returned fire with his rabbit gun, killing his nephew. A jury found Stroud not guilty, presumably on grounds of self-defense.

Casual violence soon gave way to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.9.2021 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-0983-6840-1 / 1098368401 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-0983-6840-1 / 9781098368401 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 27,0 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich