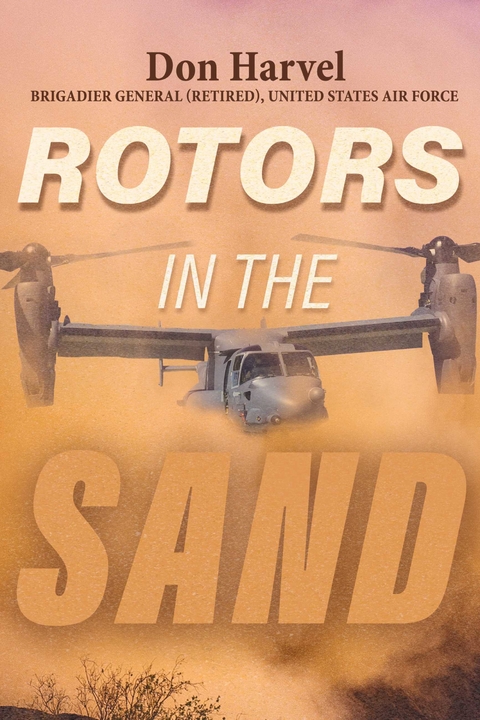

Rotors In The Sand (eBook)

400 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-0983-0333-4 (ISBN)

April 9, 2010 Approximate Local Time - Midnight in Afghanistan Twenty-five hundred feet over Taliban-held territory in southern Afghanistan, three U.S. Air Force CV-22 Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft droned through the inky black sky. The mission of the forty-eight U.S. Army Special Forces, Third Battalion, Seventy-Fifth Rangers aboard the airplanes was to engage in direct action with the enemy. The Air Force crews' mission - insert the Army troops close to their objective, a landing zone (LZ) near the town of Qalat in eastern Afghanistan. Major Randell Voas, a Minnesota native and twenty-year veteran commanding military helicopters, led the three-ship formation on the planned fourteen-minute trip. With a layer of high clouds obscuring the night sky, screens on his instrument panel burned green with aircraft performance and navigation information, the only visible illumination. In the cockpit, the navigation page revealed their progress - late. Anticipating the descent for landing, Voas adjusted his night vision goggles and keyed the microphone switch on his control column advising his formation of an updated time over target (TOT). The new TOT would have the three CV-22s landing on the LZ at forty minutes after midnight. Approximately twenty miles from the LZ, Voas reduced power, allowing the nose of the aircraft to fall toward the obscured horizon. He trimmed pressure on the control stick to neutral for the gradual letdown to a lower altitude. Level at six hundred feet above the ground and two minutes out, an A-10 Thunderbolt II orbiting above illuminated (sparkled) the LZ. The crew, expecting a single shaft of light to identify their objective, instead watched multiple rays of infrared energy streak toward the planned touchdown point. The copilot leaned forward in his seat questioning what he saw. With no apparent concern, Voas acknowledged and modified his crosscheck, focusing on the TOT and the approach to landing. At three miles and one minute from landing, the trio of aircraft descended to three hundred feet above the ground. The troops in the rear of the airplane acknowledged the "e;one-minute"e; advisory from the CV-22 tail scanner and took a knee facing the open ramp and door, preparing for a rapid egress once on the ground. Descending into a valley and drifting away from their desired track, the crew noted an unexpected wind shift and corrected their heading to remain on course. At two and a half miles to landing, Voas slowed to approach speed, and tilted the nacelles on the ends of the CV-22's stubby wings toward the vertical, altering their configuration from airplane to helicopter mode. The flight engineer lowered the landing gear. Hydraulic fluid compressed to 5000 psi (pounds per square inch) hissed through stainless steel lines to release the up locks fixing the landing gear assemblies into the wheel wells. Giant pistons ported fluid that extended the landing gear into position with an audible clunk. Suddenly, at one hundred feet above ground, the airplane's nose unexpectedly pitched earthward in a rapid rate of descent. Unable to arrest the aircraft's vertical velocity or his speed over the ground, and with the plane headed for the center of a deep gully, Voas elected to abandon a vertical helicopter landing in favor of a seldom-practiced emergency maneuver. With his speed slightly exceeding ninety knots, he opted to land like any fixed-wing airplane, rolling the wheels onto the desert floor. Nearing touchdown, and amid a cacophony of aural electronic altitude warnings, the tempo of cockpit conversation intensified. What caused the Osprey to suddenly fall out of the sky? Could Major Voas avert the pending disaster? The story of this accident would become a political lightning rod for over a decade. Read this exciting book to find out why.

PROLOGUE

April 9, 2010

Approximate Local Time – Midnight in Afghanistan

Twenty-five hundred feet over Taliban-held territory in southern Afghanistan, three U.S. Air Force CV-22 Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft droned through the inky black sky. The mission of the forty-eight U.S. Army Special Forces, Third Battalion, Seventy-Fifth Rangers aboard the airplanes was to engage in direct action with the enemy. The Air Force crews’ mission – insert the Army troops close to their objective, a landing zone (LZ) near the town of Qalat in eastern Afghanistan.

Major Randell Voas, a Minnesota native and twenty-year veteran commanding military helicopters, led the three-ship formation on the planned fourteen-minute trip. With a layer of high clouds obscuring the night sky, screens on his instrument panel burned green with aircraft performance and navigation information, the only visible illumination.

In the cockpit, the navigation page revealed their progress – late. Anticipating the descent for landing, Voas adjusted his night vision goggles and keyed the microphone switch on his control column advising his formation of an updated time over target (TOT). The new TOT would have the three CV-22s landing on the LZ at forty minutes after midnight. Approximately twenty miles from the LZ, Voas reduced power, allowing the nose of the aircraft to fall toward the obscured horizon. He trimmed pressure on the control stick to neutral for the gradual letdown to a lower altitude.

At six minutes from touchdown, he passed a required advisory to his crew and passengers. The two aircraft behind him followed his lead and reset the alert height in their radar altimeters to five hundred feet. The Army troops acknowledged, ensured their weapons were safe, checked that their hand-held GPS tracked normal, and lowered their night vision goggles over their eyes.

Level at six hundred feet above the ground and two minutes out, an A-10 Thunderbolt II orbiting above illuminated (sparkled) the LZ. The crew, expecting a single shaft of light to identify their objective, instead watched multiple rays of infrared energy streak toward the planned touchdown point.

The copilot leaned forward in his seat questioning what he saw.

With no apparent concern, Voas acknowledged and modified his crosscheck, focusing on the TOT and the approach to landing.

At three miles and one minute from landing, the trio of aircraft descended to three hundred feet above the ground. The troops in the rear of the airplane acknowledged the “one-minute” advisory from the CV-22 tail scanner and took a knee facing the open ramp and door, preparing for a rapid egress once on the ground.

Descending into a valley and drifting away from their desired track, the crew noted an unexpected wind shift and corrected their heading to remain on course.

At two and a half miles to landing, Voas slowed to approach speed, and tilted the nacelles on the ends of the CV-22’s stubby wings toward the vertical, altering their configuration from airplane to helicopter mode. The flight engineer lowered the landing gear. Hydraulic fluid compressed to 5000 psi (pounds per square inch) hissed through stainless steel lines to release the up locks fixing the landing gear assemblies into the wheel wells. Giant pistons ported fluid that extended the landing gear into position with an audible clunk.

Suddenly, at one hundred feet above ground, the airplane’s nose unexpectedly pitched earthward in a rapid rate of descent. Unable to arrest the aircraft’s vertical velocity or his speed over the ground, and with the plane headed for the center of a deep gully, Voas elected to abandon a vertical helicopter landing in favor of a seldom-practiced emergency maneuver. With his speed slightly exceeding ninety knots, he opted to land like any fixed-wing airplane, rolling the wheels onto the desert floor. Nearing touchdown, and amid a cacophony of aural electronic altitude warnings, the tempo of cockpit conversation intensified.

The tail scanner annunciated heights above touchdown beginning at ten feet, but before he could make the six-foot call, the main gear touched down firmly.

The nose wheel rolled a short distance then bounced, causing the open ramp to plow a furrow in the desert sand centered between tracks made by the main gear. Contacting the ground a second time, the nose gear collapsed. The now damaged airplane plowed across the desert, the nose of the CV-22 striking a shallow three-foot-deep ditch. The aircraft pivoted, tail-over-nose, crushing the cockpit, flipping onto its back. As the upside-down airplane skidded to a stop, its proprotors dug into the sand tearing the wings from the fuselage. The engines exploded, igniting fuel pouring from ruptured tanks into the hull and over the ground. The burgeoning inferno trailed the aircraft’s deadly path.

The hard points securing the copilot’s seat to the floor failed when the cockpit was crushed, sending him tumbling through a hole ripped in the aircraft’s skin and across the sand for over thirty yards. He came to rest facing the rear of the fuselage, still strapped in his seat.

The larger section of hull, aft of the cockpit, came to rest inverted facing the direction from which they had landed. With the tail section missing and the fuselage separated at the bulkhead between the flight deck and what remained of the aircraft, the cargo compartment became a hollow tube grotesquely gaping open at each end with severed wires, tubing, and structural supports protruding into the void in a random, disordered tangle.

Shocked and injured passengers disencumbered themselves from their restraints; the less impaired assisting others away from the wreckage as quickly and safely as possible.

At first thought to be dead, the tail scanner remained one of the last brought to safety. His wounds appeared so severe he was left dangling by his safety line from the floor of the cargo compartment. Only when one of the Rangers heard him moaning, was he cut from his restraints and carried away from the aircraft. Thirty yards behind the airplane, another soldier cut the dazed copilot’s restraints freeing him from his seat.

Light from the orange flames of burning jet fuel illuminated the dark night. Anticipating a rescue they were sure would soon arrive, the survivors administered first aid and triaged the wounded beneath a cloud of black smoke towering over the wreckage.

The fated Osprey flew only fourteen minutes, from takeoff to impacting the ground - less than a quarter mile short of their point of intended landing. Once on the ground, it skidded over the desert floor for seven seconds, traveling nearly three hundred feet.

Of the sixteen passengers aboard, fourteen, with varying degrees of injuries, survived. The most severe were treated at hospitals in Afghanistan and Germany, the rest at military trauma centers in the United States. Five sustained no or minor injuries, allowing their return to duty once evacuated from the crash site.

Two passengers riding in the back of the airplane died at the scene; one a U.S. Army Ranger, the other, a female civilian embedded with the unit as an Afghan interpreter.

Two U.S. Air Force members of the crew perished when the Osprey flipped onto its back, crushing the cockpit; the flight deck engineer, Senior Master Sergeant James Lackey, and the pilot, Major Randell Voas.

10 Hours Earlier

After less than a week of deployment at their main operating air base in Kandahar, Afghanistan, Major Randell Voas and his crew rose at 2:00 p.m. - dawn for special operator’s duty. Expecting to be on alert or fly that night, they ate at the chow hall closest to their quarters then drove their crew vehicle, a Polaris 4-wheeled ATV, a quarter mile over unmarked dirt and gravel roads to their squadron operations. The crew shielded their faces against the mushrooming clouds of choking dust thrown into the air by rough terrain tires on most of the bases’ vehicles, and the pungent odor of raw sewage saturating the Kandahar atmosphere.

They entered from the main base side of the semi-permanent building into a large room crews used for flight planning. Once inside, they made straight for a whiteboard where the squadron dispatcher posted general notices and the day’s schedule.

Before they could digest the hand-written information, their commander greeted them. “Good, you’re here. The Joint Operations Center (JOC) called. They require three aircraft from the Eighth Special Operations Squadron (SOS) to transport members of the Seventy-Fifth Rangers to a landing zone near Qalat … TOT around midnight. Voas, you’re senior in rank and experience. You have mission command and lead. The Planning Operations Center (POC) is drafting the mission plan. They’re ready to brief you and the other two pilots when you get there.”

Needing no further instructions, Voas’s copilot and two enlisted crewmembers departed operations for the flight line and their assigned aircraft. While his crew configured and finished pre-flighting the airplane, Voas headed to the POC....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.4.2020 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Lyrik / Dramatik ► Dramatik / Theater |

| ISBN-10 | 1-0983-0333-4 / 1098303334 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-0983-0333-4 / 9781098303334 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,8 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich