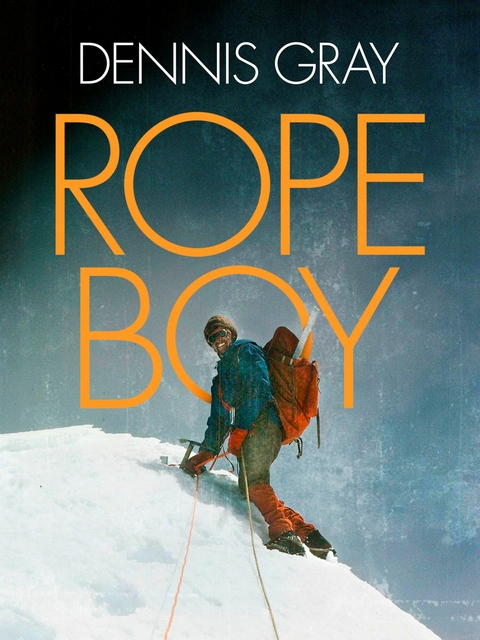

Rope Boy (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-910240-91-5 (ISBN)

Dennis Gray first climbed as a schoolboy, with the 'Bradford Lads', a group that emerged in the 1940s and remained united for many years. In 1954, when called up for National Service, he was posted to Manchester where he would go on to climb with the finest talent in the country: members of the Rock and Ice club - Joe Brown, Don Whillans, Merrick 'Slim' Sorrell, Ron Moseley, Nat Allen, and many others. A brief posting to Innsbruck in 1955 gave him his first taste of Alpine rock, and countless more Alpine visits then followed throughout the sixties, as well as a visit to the Himalaya, which led to the first ascent of the Manikaran Spires. In 1966 he led an expedition to film the first complete ascent of the north ridge of Alpamayo in the Cordillera Blanca range in the Peruvian Andes, and two years later led another which made the first ascent of Mukar Beh in the Kulu valley in India. Gray became the first general secretary of the British Mountaineering Council (BMC), a position he held for eighteen years until 1989, before later guiding in Morocco, the Atlas Mountains, and the Himalaya. He then returned to academia and has written three papers about various aspects of development in China, after some time spent lecturing in China and researching in Oxford. He founded the Chevin Chase cross-country race in 1979, one of the most popular running events in Yorkshire, and has published seven books including a novel, a book of poems, and two books of anecdotes and stories. He lives in Leeds, and has three grown children and five grandchildren.

‘Lowliness is young ambition’s ladder.’ (Julius Caesar).

The West Riding of Yorkshire is an area of remarkable contrasts: squalid industrial belts, sprawling villages, high moorland littered with gritstone outcrops, idyllic dales. To the casual visitor the industrial areas will probably appear dirty and oppressive, but let him probe beneath the surface of daily life and he will find a quality of existence rare for such an environment, reflected by the inhabitants’ love of choral singing, brass bands, cricket, fish and chips, and of the dales, moors and rocks of their native Riding. Despite appearances, anyone living here is ideally placed to become a climber, a fact highlighted by the many West Riding mountaineers who, from modest beginnings on small gritstone outcrops, have progressed to the great mountains of the world.

I was born in October 1935, in Leeds, a manufacturing city with one redeeming feature – the ease with which it is possible to reach open countryside to the north. My father was a Dalesman from Wharfedale and my mother Liverpool Irish. My father followed an unconventional profession as a club and stage entertainer, and my sister and I grew up in an atmosphere of show business talk, among club and theatre people – singers, musicians, comedians and the like. My early memories are of piano singsongs, nights spent in station waiting rooms, artists rehearsing in our sitting room, of easy laughter and tears.

My parents had met when my father was on tour and although a love match their marriage was often in stormy waters, if not actually on the rocks. We lived in a large, broken-down Yorkshire stone house in one of the poorer districts of Leeds and, partly because of my parents’ open-handedness, partly because of a large sitting-cum-rehearsal room, our abode was a centre for many local artists. My mother was the happiest of women, usually singing as she worked at her household chores, generous and kind and always prepared to sacrifice herself for her children’s sake but, true to her Irish temperament, was not to be argued with if roused or annoyed. Our family knew poverty and occasional riches, according to the bookings on my father’s engagement calendar. Some weeks we lived mostly on bread and dripping or bread and sugar, other weeks we lived like lords. My father, as a true man of the stage and generous to a fault, immediately spent or lent what he earned. My sister and I learnt at an early age to fend for ourselves and were used to travelling. My sister took up singing professionally at fifteen, but I hated the entertainment business and never wanted to follow in my father’s footsteps.

When I was eleven and a pupil at Quarry Mount Primary School, I joined the local Boy Scout troop in Woodhouse, another of the poor quarters of Leeds. Occasionally the Scouts planned a hike, and the month I joined a Sunday walk was to take place over Ilkley’s famous moor. This was early in 1947 and to most of the boys in the troop such an outing was an adventure, since none of their parents owned transport and a few of them had never been out of Leeds.

We were instructed to catch the first bus from Leeds to Ilkley. On the appointed day I caught what I thought was the first bus, a few stops from its starting point, but to my disappointment none of my fellow Scouts was aboard. I reasoned that this must be a duplicate bus and that doubtless they would be waiting in Ilkley when it arrived. An hour later, at journey’s end, I was again disappointed; none of my friends were there and I wandered the streets looking for signs of them without success. I had obviously missed them, but I knew that the route planned was up to Ilkley Moor and on to the Cow and Calf rocks, the popular viewpoint looking over Wharfedale; from there they would go back by a roundabout route over the moors to Guiseley. If I hurried I might cut them off by going direct to the rocks by the road instead of crossing part of the moor.

I ran as fast as I could up the steep hill road, arriving breathless at the Cow and Calf; after a rest I began to search for my companions. At the side of the rocks furthest from Ilkley is Hangingstone Quarry, much frequented by rock climbers, and into this I wandered in my search. There was no sign of the Scouts, but a group of climbers stood gazing intently up at the opposite quarry wall. Most small boys are inquisitive and I was no exception. Clutching my bottle of lemonade, haversack on back, I nervously edged up to the crowd to see what held their attention.

A tall, athletic, white-haired man was balanced on what appeared to me a vertical, holdless face. Nonchalantly he pulled a handkerchief out of his trouser pocket and blew his nose, to the delight of the watching climbers, and reminding me of a stage acrobat. He began to move upwards, and this was somehow immediately different from a stage show; his agility, grace of movement, control and, above all, the setting high above ground, with no apparent safety devices, sent a thrill through my young body such as I had never before experienced. I had read about mountain climbing but my reaction hitherto had been indifference. One of the group whispered to a newcomer ‘It’s Dolphin!’ as if this would immediately make clear why they were watching. The knot of climbers murmured their approval as the white-haired man reached the top of the rock face, and from the efforts of another of them to follow on a rope thrown down to him, it was obvious that Dolphin must be a gifted climber. The face was only forty feet high but to me it could have been three times that height. I forgot all about my hopes of meeting my fellow Scouts and sat watching for hours. Always Dolphin was the most impressive and I gazed in wonder as he moved up vertical walls and fissures with speed and ease; his mastery held me spellbound. Then suddenly I saw him and some others changing into running shorts, replacing nailed boots with gym shoes, parachute jackets with vests, and before I realised what they were at they had disappeared on to Ilkley Moor.

Although shy, I ventured to ask one of the remaining climbers a few questions about his sport and in particular about the man who had impressed me so much. Good-naturedly he explained some of the techniques involved in rock climbing and told me that I had been watching ‘Arthur Dolphin, the best rock climber in the area’. I thanked my informant, looked around once more for the Woodhouse Scouts, then set out across the moor to find my way to Guiseley and a bus home. Walking along I suddenly startled myself with the idea ‘I would become a climber like Arthur Dolphin’. Up to that moment my ambition, like that of every other small boy at Quarry Mount School, had been to become a cricketer and play for Yorkshire; this was now relegated to second place in my future hopes. My next realisation was equally disturbing – I didn’t care about missing the Woodhouse Scouts; the unexpected revelation of the sport of climbing had been worth my trouble.

Once the desire to climb is implanted in a person, it is extraordinary to what lengths he will go to achieve his objective. I have known people sacrifice their livelihood, ignore family obligations, drop career chances in order to learn to climb. Luckily for me, despite my youth it was not difficult to find someone to take me climbing, for in our Scout troop one of the older boys, John Collins, did climb and owned a rope. He was a regular visitor to Ilkley and Almscliff Crag and I badgered him into taking me with him to the Cow and Calf rocks on his next visit.

Climbing in 1947 was vastly different from what it was to become only a decade later. The country was still recovering from the aftermath of war, rationing was a feature of everyday life, and the standard of living for the majority was low. Equipment was rudimentary or homemade, and most of the climbers were dressed in ex-war department surplus – camouflage trousers, parachute-brigade jumping jackets, berets and so on. If they owned a rope it was of manilla, hemp or sisal, and few had boots made specially for climbing; most had walking or ex-war department boots, nailed with Tricounis, clinkers or triple hobs. In dry weather, gym shoes were occasionally worn, especially for tackling hard climbs, but the majority climbed in boots most of the time. Few climbers understood the use of running belays, mainly because of the lack of karabiners on the market; the few there were had ex-war department as their point of supply and would never have passed today’s stringent UIAA (Union Internationale des Associations d’Alpinisme)tests. It used to be said at that time that ‘if there had been no war, British climbers would have had to go naked, dressed only in the coils of their ropes’.

My first climb at Ilkley with John Collins and another local climber known as Lazarus was the Long Chimney in Rocky Valley, an edge on Ilkley Moor not far from the Cow and Calf rocks and Hangingstone Quarry. Though one of the longest climbs at the rocks, over fifty feet, it is relatively easy, but paradoxically graded Very Difficult. So impressed was I by this ascent, so difficult did I find the chimney, that I nearly went back on my resolve to become a climber. I could not face attempting another climb that day; my nervous energy had been utterly spent and I preferred to watch other people from the safety of the ground. One good thing about extreme youth is that setbacks are easier to overcome and, despite my poor performance and obvious lack of natural ability, a fortnight later found me back at Ilkley determined...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.10.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Nord- / Mittelamerika | |

| Schlagworte | almscliff • Alpamayo • ALPINE • Arthur Dolphin • Bradford Lads • Cairngorms • Chris Bonington • Climb • Climbing • climbing books • Cloggy • Clogwyn Du'r Arddu • Creag Meaghaidh • Dennis Gray • Dennis Grey • Dick White • Don Chapman • Don Cowan • Don Whillans • dougal haston • Hamish MacInnes • High Tatra • Himalaya • hitch-hike • Ilkley Moor • India • Joe Brown • Lake District • Langdale • Manchester • Merrick Sorrell • Mont Blanc • mountaineering book • mountaineering books • Mukar Beh • Nat Allen • Northern Bens • Peru • Rock and Ice • Rope Boy • Rope Boy, Dennis Gray, Dennis Grey, climbing, climbing books, climb, mountaineering book, mountaineering books, Rock and Ice, Bradford Lads, Don Whillans, Arthur Dolphin, Joe Brown, Nat Allen, Yosemite, Scotland, Scottish climbing, wales, Cloggy, Clogwyn Du'r Arddu, Alpamayo, Mont Blanc, Northern Bens, alpine, High Tatra, Mukar Beh, Himalaya, Manchester, Ilkley Moor, almscliff, Lake District, Langdale, Wasdale, hitch-hike, Merrick Sorrell, Slim Sorrell, Don Chapman, Don Cowan, Dick White, Cairngorms, Creag • Scotland • Scottish climbing • Skye • Slim Sorrell • Tom Patey • Wales • Wasdale • Yosemite |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-91-5 / 1910240915 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-91-5 / 9781910240915 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 30,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich