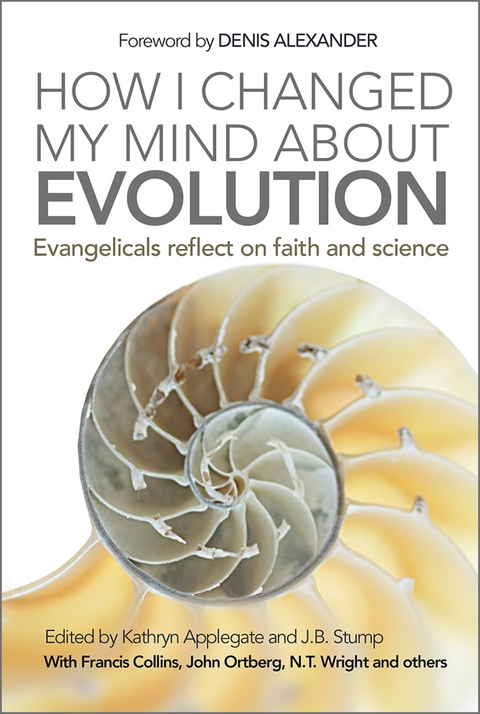

How I Changed My Mind About Evolution (eBook)

208 Seiten

Lion Hudson Plc (Verlag)

978-0-85721-788-2 (ISBN)

- 1 -

From Culture Wars to Common Witness

A Pilgrimage on Faith and Science

James K. A. Smith

James K. A. Smith is professor of philosophy at Calvin College and a senior fellow of The Colossian Forum. His most recent book is Who’s Afraid of Relativism? (Baker Academic, 2014). He and his wife, Deanna, have four children and are committed urban gardeners.

Strangely (and sadly) enough, it was Christians who taught me how to fight. Since I was not raised in a Christian home, I didn’t receive the standard evangelical formation in the faith (Christian schooling, youth group, summer camps concluding with heartfelt renditions of Michael W. Smith songs). So I also didn’t absorb the common evangelical sense of the “fault lines” that defined our culture.

However, when I became a Christian at the age of eighteen, I quickly made up for this. I drank up the Bible and consumed whatever mode of Bible teaching I could find (I’m old enough, I confess, that most of this was from huge catalogues of cassette tapes by noted Bible teachers). I abandoned my plans to become an architect, immediately sensed a call to ministry, and enrolled in Bible college. My first year at Bible college was a veritable boot camp in what I would only later learn to describe as “the culture wars.”

Perhaps surprisingly, it was at Bible college that I was first taught to care about science. That might strike some as odd, since we often perceive Bible colleges as anti-intellectual zones of hostility to science. But that picture needs to be corrected a bit. In my Bible college experience, I was energized by a new interest in science bequeathed to me by the energy and passion of my apologetics teacher. A former naval engineer with a PhD in chemical engineering, “Dr. Dave” had experienced a radical conversion and also sensed a call to ministry. After spending time at seminary, he devoted himself to a teaching ministry that eventually landed him at the Bible college where his responsibilities were apologetics and “Christian evidences.”

His passion and knowledge were infectious. I soaked up his fascination with archaeology (a historical science). I was awed by his presentation of geological evidences of the flood and cosmological evidence for creation. Here I was at Bible college, being invited to think about carbon dating and the Doppler effect and the geological science of sedimentation (the volcanic impact of Mount St. Helens was always a favorite case study). As someone who had skated through high school with little to no interest in science, I would never have imagined that going to Bible college would pique my interest in everything from molecules to galaxies.

Dr. Dave noted my curiosity and began to express personal interest, taking me under his wing as a kind of apprentice. Indeed, while the intellectual component fostered my curiosity about “creation science,” I think it’s crucial not to underestimate the personal and pastoral factors at work here as well. In significant ways, I cared about creation science because Dr. Dave had clearly demonstrated that he cared for me. I was open to being intellectually convinced precisely because I had already sensed that I was being pastorally cared for. My mind was open to creation science because Dr. Dave had expressed love and concern for my soul. I sensed a symbolic culmination of all of this when he gave me a personal copy of Ian Taylor’s (rather infamous) book, In the Minds of Men: Darwin and the New World Order. It still sits on my shelf, no longer because I value the arguments it contains, but because I’m grateful for the love with which it was given.

Not until later did I realize that, in my Bible college education, science was primarily of interest as ammunition in a culture war. I don’t mean to suggest there wasn’t genuine interest or curiosity in features of God’s creation and the intricacies of the physical world. I only mean that this curiosity was circumscribed and selective and instrumentalized. Science was of interest insofar as it contributed “evidences” that would help win an argument, defeat an opponent and shore up a “position” in the culture war. Science was not entertained as a vocation or calling for Christians. Instead, science was something we could use—and use as a weapon.

In addition, it gradually became clear to me that the “science” I was being offered was a very selective sampling of data and evidences that exhibited a kind of confirmation bias: unlike the sort of open curiosity—and openness to being wrong—that characterizes genuine scientific exploration of the physical world, my teachers were primarily interested in science that confirmed a certain reading of the Bible (specifically, a young-earth creationist reading of Genesis). I started to get an inkling that maybe I hadn’t gotten the whole story—that maybe there was a lot more to science than flood geology and critical questions about carbon dating.

Interestingly enough, the seeds of my critical distance from this sort of “science” were also sown at the same Bible college—through an encounter with Christian theologians associated with “Old Princeton.” (In Book VIII of Augustine’s spiritual autobiography, The Confessions, he recounts his conversion through his encounter with several important books. My “conversion” with respect to faith and science is also a history of encounter with important books. Who knew libraries could be evangelists?) In some of my courses in systematic theology, my professors regularly referred to the rich heritage of Reformed thinkers that included B. B. Warfield, Charles Hodge, A. A. Hodge and others. Being a Bible and theology geek, I scoured the college library for anything and everything by these august scholars and Bible commentators. I camped out in the basement library for hours on end surrounded by their works. Whenever I could scrabble together a few dollars, I added another Warfield or Hodge to my growing personal library. My “upstairs” education in the classrooms of the Bible college were supplemented by a “downstairs,” parallel education in “Old Princeton” Reformed theology. And in their work—already in the 1800s—I found quite a different posture toward science.

This all crystallized when I hit upon Mark Noll’s excellent anthology, The Princeton Theology 1812–1921: Scripture, Science, and Theological Method from Archibald Alexander to Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield. Here I first encountered the writings of orthodox, conservative, Reformed evangelicals who were open to—and affirmative of—developments in evolutionary science. Indeed, Warfield had been cited by my professors as one of the great defenders of biblical inerrancy; but they hadn’t told me about his very favorable stance towards evolution. And so some of my former sureties began to crumble. I began to sense that science was bigger than what I had been taught, and that evangelical Christians need not be characterized by fear or a posture of defense, but could be open and curious about new developments. Most importantly, I began to realize that science need not just be an apologetic weapon. Scientific exploration could be a good in and of itself, even if that exploration might take us into places that could be unsettling.

This season in my life was a turning point in many ways. In particular, it was at this juncture that my pilgrimage in faith took me toward the Reformed tradition. (I discuss this in more detail in my little book Letters to a Young Calvinist: An Invitation to the Reformed Tradition.1) This had repercussions for every sector of my thinking, including how I thought about science. But what I absorbed from the Reformed tradition was also a stance toward history and the historical riches of the Christian tradition. The Reformation was a renewal movement in the church catholic that was birthed by the Reformers’ recovery of ancient Christian sources, mining the wisdom of church fathers like Augustine and Chrysostom. That means the Reformed tradition is characterized by a sense of chronological deference, in a way—a sense that we have much to learn from what has gone before, even a certain healthy skepticism about theological novelty.

This sensibility dovetailed with my encounter with another important book in my pilgrimage: Ronald Numbers’s The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism. In this meticulous history, Numbers demonstrates the utter novelty of young-earth creationism as a biblical hermeneutic (a direct parallel to the utter novelty of dispensationalism as a way of understanding the eschatology of Scripture). Because my pilgrimage in the Reformed tradition had instilled in me a sense of indebtedness to the riches and legacy of the historic Christian faith, the newness and novelty of “scientific creationism” gave me serious pause. And I began to realize that the way I had been taught to read the Bible alongside selective presentation of scientific data was, in fact, quite aberrant in the history of Christianity—a modern hermeneutical invention that was strikingly different from the way the Bible had been read from Augustine to John Calvin. So in a way, it was discovering the orthodox voices of Augustine and Calvin and Warfield that made me suspicious of the notion that I needed to be a young-earth creationist in order to be...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.7.2016 |

|---|---|

| Illustrationen | Jim Stump |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Evolution | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85721-788-7 / 0857217887 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85721-788-2 / 9780857217882 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich