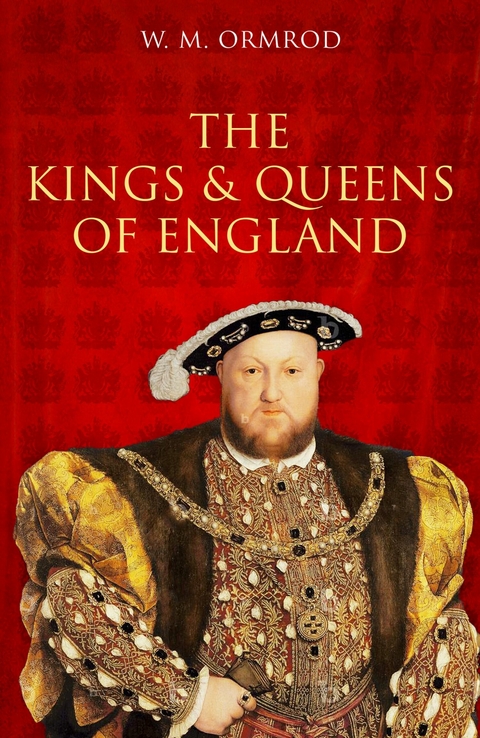

Kings and Queens of England (eBook)

336 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-7310-9 (ISBN)

W.M.Ormrod is Professor of Medieval History at the University of York. He has written extensively on medieval Britain: his other books include Edward III ('Instantly accessible' The Observer), also published by Tempus, along with Political Life in Medieval England, 1300-1450 (with Anthony Musson), The Evolution of English Justice: Law, Politics and Society in the Fourteenth Century, and The Black Death in England (with Phillip Lindley).

This title offers a historical context in which to appreciate the political and moral significance of both the famous and the more obscure incidents in the public and private lives of Britain's monarchs.

- 1 -

The Kings of the English from Earliest Times to 1066

Alex Woolf

In the fifth to seventh centuries AD, substantial parts of Britain were invaded and settled by a series of tribesmen from northern mainland Europe collectively referred to as the Anglo-Saxons. By the end of the seventh century, these tribes had spread out to encompass most of present-day England and much of southern Scotland. By the end of the seventh century, twelve principal Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had emerged: those of the Bernicians, the Deirans, the Lindesfarona, the East Angles, the Middle Angles, the Mercians, the Hwicce, the Magonsaete, the Gewisse, the South Saxons, the Cantware and the East Saxons. Of these, three were to become especially dominant: the Bernicians in the North, the Mercians in the Midlands and the Gewisse in the South. The spread of Christianity amongst these Germanic-speaking peoples around 600 greatly enhanced the office of king and helped to promote a sense of common cultural and political identity. The Bernician monk Bede, writing c.730, listed seven rulers in the period up to 671 who held imperium (overlordship) over all the ‘South Angles’ (by which he meant all the Germanic peoples south of the Humber, the boundary between the Deirans and the Lindesfarona). In the ninth century, the West Saxon text known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle added another more recent king to this list and gave these imperium-holders the title of Bretwalda or Brytenwalda (meaning either ‘wide-ruler’ or ‘Britain-ruler’). Under King Alfred and his successors in the tenth century, the kings of the West Saxons asserted the right to rule most of what is now England, and were an influential and sometimes dominating force over the rulers of native British peoples in parts of Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

The Kings of the Cantware (‘Kent’)

The history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms traditionally begins with the history of Kent. The reasons for this are twofold. First, Bede, followed by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, claimed that the first leader of the Germanic invaders of Britain was the same man who appears at the head of the list of Kentish kings, Hengest. Secondly, Kent was the first kingdom to receive Christianity, and thus had the oldest archive of historical documents. If we look at the pedigree stretching back from the first Christian king, Æthelbert, who died in 616, however, it is clear that Hengest cannot have lived much earlier than c.500, whereas we can be certain that the coming of the Anglo-Saxons took place at least half a century before that. Two solutions present themselves: either Hengest was not really the ancestor of the Kentish kings, or he was not really the leader of the first invasion. It is hard to choose between these two options. Archaeology, however, does suggest that there was a second Germanic influx in Kent, of a distinct southern Scandinavian tribe called the Jutes, around 500, so it is possible that Hengest was the first Jutish leader in Kent but not the first German in Britain. The dates accorded him in the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle cannot be trusted.

With Æthelbert, the third of the imperium-holders listed by Bede, we are on much firmer ground. He seems to have married a Christian princess, Bertha, from Francia (the region across the Channel in what is now the Low Countries and France) at a time when his father, Eormanric, was still king in Kent. By the mid-590s, however, he himself was king and he wrote to the pope, Gregory the Great, asking that missionaries be sent to convert his people. Gregory’s responses survive and it is clear that he believed Æthelbert was rex Anglorum – ‘King of the English’ – evidence that even at this early date the term Angli had the double meaning of ‘Angle’ and ‘Anglo-Saxon’. Gregory sent the monk Augustine to Kent, having him made a bishop on the way, to convert Æthelbert and his people. Rather curiously it is clear that Bertha, who was already a Christian, had brought with her on her marriage a Frankish bishop, Liudhard. Possibly Æthelbert was wary of Frankish political intentions towards his kingdom and may have felt that getting missionaries from Rome rather than the Frankish kingdoms was one way of preventing a fifth column from entering the country.

After Æthelbert’s death his son Eadbald succeeded to the kingdom. Eadbald (616-40) had not grasped the full implications of being a Christian. He married his father’s widow (marriage to stepmothers seems to have been quite common, as it prevented disputes over inheritance) and engaged in other activities that were regarded as pagan by the missionaries. Bishop Laurence, now the leader of the mission, managed to bring Eadbald around by convincing him that he himself had been assaulted and beaten by St Peter as a punishment for not keeping the king on the straight and narrow. Anxious for the welfare of his father’s friend, King Eadbald set aside his stepmother and returned to the fold of the Church. Eadbald further promoted the cause of the Church by giving his sister Æthelburh in marriage to the Deiran King Eadwine in 625. This helped to spread Christianity into the northern part of England. All subsequent Kentish kings were descended from Eadbald.

Kent seems to have been divided into two provinces at this time: that of the Cantware proper, with its bishop at Canterbury, and, west of the Medway, another province with a bishop at Rochester. Archaeologically, West Kent had more in common with East Saxon territories just across the Thames than it did with the Jutish East Kent. The west sometimes had its own kings as well. At times these were junior members of the Jutish dynasty, but some of them had names like Swæfheard and Sigered, which look suspiciously East Saxon. It is perhaps best to think of the land between the Medway and the Thames as debatable, sometimes looking north and sometimes east.

Of the later kings, the most notable are Hlothere (673-85) and Wihtred (690-725) who both produced law codes, expanding on a practice begun by Æthelbert. The three Kentish codes attached to the names of these kings are the earliest English law. After Wihtred, the importance of the Kentish kings declined. They lost out to the growing power both of the Mercians and of the church at Canterbury, which now housed an archbishop claiming ecclesiastical jurisdiction throughout Britain. The second half of the eighth century saw direct Mercian intervention, including the imposition of Midland princes into the kingship (Cuthred, 798-807, and Baldred, 823-5). In 825 the kingdom was ‘liberated’ by the West Saxons, who subsequently bestowed it on their heirs apparent. After 860 it became fully absorbed into their kingdom.

The Kings of the East Angles

The kingdom of the East Angles was probably more powerful than the surviving sources would suggest. This is the region of England that was most severely affected by the Viking invasions of the later ninth century, and no native documentation has survived. It contains the richest pagan burial yet recovered from Anglo-Saxon England: the famous ship-burial at Sutton Hoo. This has been claimed as the burial, or at least cenotaph (no body was found), of King Rædwald (d. c.625), the grandson of Wuffa, from whom the royal dynasty was named the Wuffingas. Rædwald is said to have converted to Christianity at the court of Æthelbert of Kent, but to have been persuaded by his wife not to renounce paganism altogether. This, it is argued, explains the presence of Christian paraphernalia in the Sutton Hoo tomb, despite its generally pagan character. Rædwald clearly put a lot of store by his wife’s advice, for some years later he received messengers from Æthelfrith of Bernicia offering him great rewards if he would murder or hand over Eadwine, an exiled Deiran prince who was a warrior of his household. When she heard of this, the queen told Rædwald that to do such a thing would dishonour him before all men, so he changed his mind and instead went to war with Æthelfrith. In a battle on the River Idle in Nottinghamshire, he slew the Bernician king and was subsequently able to place Eadwine on the Deiran throne. It is probably this great victory that made him one of Bede’s imperium-holders.

Rædwald’s son and successor Eorpwald converted to Christianity properly but was slain by his pagan subjects in c.627, and the kingdom remained pagan for a further three years. In c.631 Rædwald’s stepson Sigibert returned from exile in the Frankish kingdom, converted, and began to promote Christianity. Within a few years he retired to a monastery but returned to the world when an invasion by the Mercian King Penda took place. He was killed in battle (c.637) and was succeeded by Rædwald’s nephew Anna. Anna lasted until about 654, when he too was killed by Penda, who seems to have been supporting a bid for power by Anna’s brother, Æthelhere. Æthelhere died the following year, alongside Penda, in battle with the Bernicians at Winwæd.

Of the deeds of later kings we know little. King Ealdwulf (663-713) seems to have been a great patron of the Church even though he could remember that pagan temples remained standing in his own childhood. As in Kent, conflict with the Mercians dominated the later history of the East Angles. One king, Æthelbert (779-94), was invited to the court of the Mercian King Offa and summarily executed. His body was taken to Hereford (near where the execution had taken place) and his grave became the site of a cult. The ninth-century kings are known mostly from their coins and some of them may have been Mercian, or even West Saxon, intruders. In 869 King Edmund, a young warrior, was...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.10.2011 |

|---|---|

| Co-Autor | The British Library |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Hilfswissenschaften | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | british monarchs • British royal family • english monarchs • Kings • kings & queens • kings & queens of england • Monarch • monarch, monarchy, royals, royalty, royal family, sovereign, kings, queens, kings, queens, political, moral, private lives, public lives, english monarchs, british monarchs, british royal family, kings & queens of england, kings & queens • Monarchy • Moral • Political • private lives • public lives • Queens • Royal Family • Royals • royalty • Sovereign |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-7310-7 / 0752473107 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-7310-9 / 9780752473109 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich