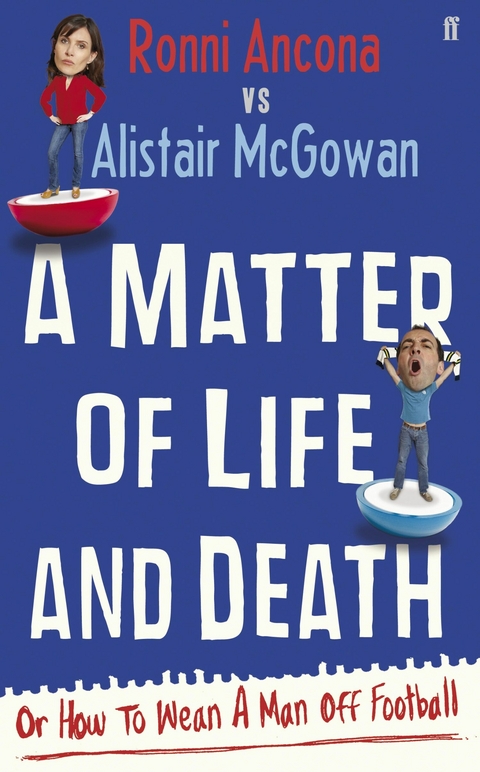

Matter of Life and Death (eBook)

272 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-25056-1 (ISBN)

Alistair is probably best known to British audiences for The Big Impression which was, for four years, one of BBC1's top-rating comedy programmes - winning numerous awards, including a BAFTA. He started out as a stand-up comic, and since his success with The Big Impression has appeared regularly on television and radio. In the Autumn of 2009, he'll be embarking on a stand-up tour around the UK.

"e;Couples argue about a lot of things - money, seeing old partners, football, having children, looking after children...and football. Clothes, washing up...and football. If you think about the relationships you've had, football is probably the cause of more arguments than anything else."e;From TV's funniest male/female double act comes a hilarious new book about the wrangles, rows and off-side rules of relationships. Ronni's challenge is this: to wean a die-hard football fan off the not-so-beautiful game. She needs a guinea pig on whom she can try out her theory. Who better than her best friend and ex-boyfriend, the truly obsessed Alistair McGowan? If she can persuade Alistair and all the men like him that there are more fulfilling ways of spending time than reading sports pages and watching Match of the Day, then surely she will help women all over the world to richer, more rewarding romantic lives. But could Alistair every really give it up? And if he did, what would remain of the man?Part comic self-help book, part confessional memoir, A Matter of Life and Death is a brilliant and original take on the differences between men and women.

lt;p>Alistair is best known to audiences for The Big Impression which was one of BBC1's top-rating comedy programmes - winning numerous awards, including a BAFTA in 2003.

Ronni Ancona was the joint winner, with Alistair for their work on The Big Impression and was named Best Actress at The British Comedy Awards in 2003. Ronni lives in London with her husband and two daughters.

So, Ronni wants me to give up football!

I went round to see her last night; she was raving about Frank Lampard being in the house. I thought she was either becoming unhinged or being burgled by a slightly overweight sporting celebrity and went to help her out.

Then she conveniently sprang this idea on me. Waking up this morning, I thought it had been a dream. It was like I was going out with her again. And we were living in Clapham again. And eating overcooked spaghetti and underflavoured bolognaise again (Ronni’s speciality) and she was badgering me about the evils of football.

Even then, Ronni had tried to point out the negative side of football to me, to show me how much of my time it was taking up. But there was no way I could have totally given up then or now.

Or could I?

I love football. Most days begin with me reading the back pages of the newspaper and most days end with a quick look at the results on Ceefax. Sound familiar?

For most men, football is a life choice. Once you’re in, you’re trapped. It’s like a personal pension scheme. You put all this effort and money and time into it and don’t get back anything like what you had imagined ‘at the end of the day’. You know that but you can’t give it up. It’s like cigarettes and alcohol: it makes no sense really, I suppose, but you do it because at some point someone, somewhere got you addicted.

I guarantee any man who hasn’t fallen in love with football as a small boy is now either a dancer in a West End show or a mini-cab driver who only works until four in the afternoon and then goes home to play backgammon on the internet. Or he likes rugby.

I mean, she’s right: there is too much football on television. It is overrated. It does stop men from talking and thinking about the wider issues of the world. It is a refuge. But my love affair goes back to when I was four. It’s part of me, part of what makes me a man. It balances my love of neatness and musicals. Could I seriously tidy up and listen to Hello, Dolly! as often as I do without also having a healthy dose of football in my life? No. To give it up would be impossible. Emasculating. I won’t do it!

Seeking to re-establish my maleness – and because there were a couple of games played last night in the lower leagues – I switch on the television and press the text button on the remote.

Page 302 – the football headlines with my morning toast and Marmite. Then the league tables on pages 324–7. Pages beloved of every football fan in Britain. There is probably an easier way to access all this info in this technological age – you can probably have it sent to your brain via your mobile or something – but Ceefax is what I’ve done for twenty years and the habit, the comfort, the tradition of it is part of my life.

I read and scour the neat lists of place names and numbers, division after division. Half an hour has gone by when I find myself still staring at League Two (the old Fourth Division) and working out how many points Rochdale are from the play-off places, when I wonder why I’m doing this.

There is a whole world outside. There are birds and clouds; hills and trees. There are films and books and plays and music to be seen and read and seen and heard. What does it matter to me – a man who has never been to Rochdale, a man who could barely point Rochdale out on a map of England (or a map of Rochdale). I know that their ground is called Spotland and that they haven’t been outside the bottom division of English football in over thirty-five years, yes. But why, right now, do I need to know in what position Rochdale lie in the football league tables, with how many points and what goal difference? Why does it matter? There isn’t going to be a test. And yet I’ve done this in some form or other since 1971. It’s tradition, it’s habit. It’s addiction.

And I thought I had this under control.

I call Ronni.

‘You’re right, Ronni. I’ve got a problem.’

‘And you’re going to let me help you?’

‘I don’t know about giving it up but I’d like to cut down.’

‘Okay … well, that’s a start.’

‘I just found myself looking at Ceefax and working out how many points Rochdale were off the play-off positions and I …’

‘Hold your horses!’ Ronni has a fondness for outdated expressions. ‘Firstly, does anyone still use Ceefax? Thirdly …’

‘What happened to secondly?’

‘Secondly, what are play-off positions? And thirdly, who are Rochdale?’

‘Exactly!’

‘Okay, this is the first thing you’ve got to do for me. Are you listening …?’

Ronni has a mildly annoying habit of asking you if you’re listening to her when you clearly are. She is either buying herself time while she thinks what she’s going to say, or she knows that if she were the one listening, her mind would be wandering all over the place and would need calling back to attention.

‘You must’, she says, ‘work out where your addiction comes from, why it started. And then, maybe, we can look at why you still need to feed it.’

‘This sounds like analysis.’

‘It is. In a way. It’s also what happens in Hitchcock’s Spellcheck.’

‘What?’

Ronni has a problem with proper nouns – she always calls things what she wants them to be called, not what they are called.

‘It’s Spellbound, not Spellcheck.’

‘That’s what I said.’

And she doesn’t ever believe she does it.

‘Anyway, Ingrid Bergman says it to Gregory Peck. We need to find the root cause of your problem and then, if we can acknowledge that connection, cut that link with the past, maybe we can make you better.’

‘That was a terrible Ingrid Bergman impression.’

‘I wasn’t doing her, I was just vaguely quoting the sentiment of the film.’

‘Okay. Shall I come round?’

‘No, come tomorrow. But promise me you’ll think about this, Ali.’

Ronni, like an earnest six-year-old, always wants everything promised. It was only at the age of twenty-eight that she stopped following it up with ‘cross your heart and hope to die’.

‘I promise,’ I say.

‘Cross your heart and hope to die?’ She’s obviously recently lapsed back into that old habit.

‘Yes.’

‘Yes, what?’

‘Cross my heart and hope to die,’ I mumble.

‘Well done, Ali! You’re doing this for the nation. For the men of the country and for the women of the country. Imagine pleasing thousands of women at the same time!’

‘I often do …’

‘Stop it!’

I put the phone down. I had a problem. And I’d acknowledged it. I felt like an alcoholic at his first AA meeting. I’d stood up and I’d said it: ‘I’m Alistair and I have a problem with football.’ I looked in the mirror. I felt like the smoker who’s just realised that everything they own, everything they touch smells of old smoke, that the warnings on the packets aren’t just there to teach people the words for ‘Smoking Kills’ in ten different languages. I felt like the sinner in those films where everyone’s wearing dungarees and dusty hats who’s just run into the church and shouted, ‘Brothers and sisters, I have seen the light!’

Everything was clear. I was an addict and I needed help. Now, what had she said? My ‘root cause’ …?

My father played football with me in the garden from a young age. A ball is one of the first things a father will buy for his son. Even before the child can walk, chances are that the impatient dad will hold his gurgling boy behind a ball and encourage him to swing a puppy-fat leg at it. My dad was a fine footballer, cursed with bad eyesight. In fact, he was a fine all-round sportsman. He grew up in Calcutta as an Anglo-Indian (as I discovered three years after his death on BBC One’s Who Do You Think You Are?) and had been chosen for India’s hockey squad for the 1948 London Olympics, but chose not to go for reasons which even the BBC’s researchers couldn’t uncover. He’d been asked to go to America to train as a professional boxer but again had not followed up the interest. He played every racquet sport available (frequently barefoot) with a natural instinct, a smile on his face and a pipe in his mouth.

And, after moving to Worcestershire and marrying my mother, he’d played football for the local team in Offenham well into his forties. When I was a boy, he’d regale me with stories of spectacular goals he’d scored, and in my mind My dad was a mixture of Bobby Charlton (the hair), Pelé (the build and the eyes) and Stanley Matthews (the wizardry and the age). When you believe that your father is three of the greatest footballers ever to have played the game rolled into one, you’re going to be hooked.

My father was a schoolteacher, so our hours were the same and we played together in every free moment: tennis, badminton, squash, chess, draughts – and football. We wore patches in the lawn in every garden of every house we lived in. I was normally in goal, throwing myself around, and Dad would take shots at me. High, low, soft, hard, left foot, right foot, on the volley … ‘Catch it!’ he’d shout, as annoyed as Brian Clough if I spilled a shot or palmed one away into the chrysanthemums for ‘a corner’.

Strangely, my father had never really followed the professional game to any degree before I came along. Not being born in England, he had no connection with any city or club, and our home in Evesham was a long way from any...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.10.2009 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Comic / Humor / Manga ► Humor / Satire |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Familie / Erziehung | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Partnerschaft / Sexualität | |

| Schlagworte | Comedy • Football • Men & Women • relationships • Television |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-25056-4 / 0571250564 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-25056-1 / 9780571250561 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 306 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich