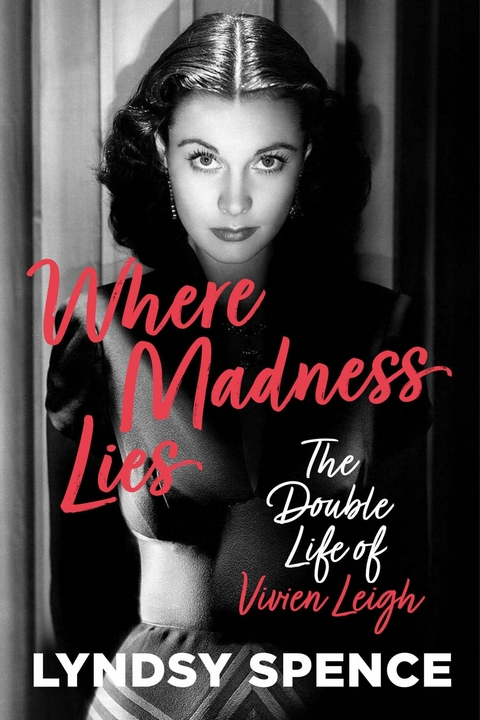

Where Madness Lies (eBook)

256 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-432-1 (ISBN)

Her meteoric rise to fame launched her into the gaze of fellow rising star Laurence Olivier. A tempestuous relationship ensued that would last for twenty years and captured the imagination of people around the world.

Behind the scenes, however, Leigh's personal life was marred by bipolar disorder, which remained undiagnosed until 1953. Largely misunderstood and subjected to barbaric mistreatment at the hands of her doctors, she also suffered the heartbreak of Olivier's infidelity. Contributing to her image as a tragic heroine, she died at the age of 53.

Where Madness Lies begins in 1953, when Leigh suffered a nervous breakdown and was institutionalised. The woeful story unfolds as she tries to rebuild her life, salvage her career and save her marriage.

Featuring a wealth of unpublished material, including private correspondence, bestselling author Lyndsy Spence reveals the woman behind the legendary image: a woman who remained strong in the face of adversity

LYNDSY SPENCE is a bestselling author and screenwriter. Her books include The Mitford Girls' Guide to Life, The Grit in the Pearl: The Scandalous Life of Margaret, Duchess of Argyll, The Mistress of Mayfair: Men, Money and the Marriage of Doris Delevingne, and Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas. Her book on Maria Callas is being adapted into a documentary by a double-Oscar nominated production company and she is producing a documentary on the Latin-American icon, Selena.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Schlagworte | 1930s • 1940s • 1950s • 50s medicine • Actor • Actress • A Streetcar named desire • british theatre • classic film • classic hollywood • Fifties • Film Culture • Filmstar • fire over england • fourties • Golden age of Hollywood • Gone with the Wind • Hollywood • lady olivier • Sir Laurence Olivier • The Double Life of Vivien Leigh • thirties • Vivien Leigh |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-432-0 / 1803994320 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-432-1 / 9781803994321 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich