Liverbirds (eBook)

320 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-37705-3 (ISBN)

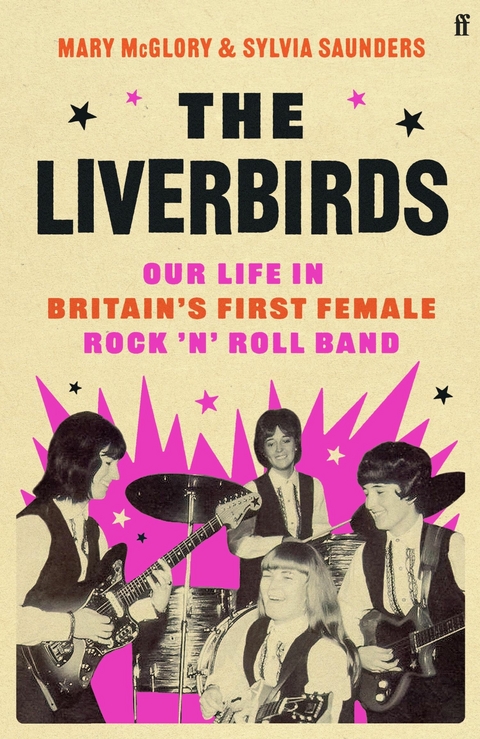

The Liverbirds were one of the world's first all-female rock 'n' roll bands. Consisting of bassist and vocalist Mary McGlory, drummer Sylvia Saunders, vocalist and guitarist Valerie Gell, and guitarist and songwriter Pamela Birch - they started on the Merseybeat music scene in 1963. They achieved success in the UK and Europe, particularly in Germany where they were a top attraction at the Star-Club in Hamburg and reached No.5 in the German charts. The group were active for five years and in that time recorded two hit albums, toured stadiums and played with the Kinks, Rolling Stones and Chuck Berry. Pamela died in 2009 and Valerie in 2016. Mary lives in Hamburg and Sylvia in Lancashire.

'In Liverpool everybody wanted to be in a band. On every street corner and in every cellar there were young fellas practising with guitars. But it was rare to see any girls on the new Merseybeat scene. It was inevitable that we would find each other . . .'In the early '60s, four friends from Liverpool formed a band. But this is not the 'fab four' story we know. Mary, Sylvia, Valerie and Pamela - also known as The Liverbirds - were one of the world's first all-female rock'n'roll bands. At an early gig, backstage at the Cavern Club, a young John Lennon told them that 'girls don't play guitars'. But they took that as a challenge. Despite the early scepticism, they won over tough crowds, toured stadiums, recorded two hit albums, and played with the Kinks, Rolling Stones and Chuck Berry - all in the space of just five years. Now, the two surviving members of the band tell their incredible story in full for the first time - capturing a lost era of liberation and rock'n'roll, as they thrived in the vibrant Merseybeat music scene and formed a friendship that has endured through the decades. *'A ton of Liverpudlian grit, good sense and wry humour.' - Daily Mail'Warm and vivid . . . Stories like this one are vital to keep.' - Telegraph'A powerful story, one that dances to its own distinctive beat.' - The Sunday Times

I remember happy times playing with other kids in bombed-out houses, what we called ‘the bomby’. Living in Burlington Street felt cosy and safe. It was a small third-floor flat in old Victorian terraced housing near the docks, with a view of the chimneys of the Tate & Lyle sugar factory. The neighbours were close by, walking in and out of the flats, or drinking together in the Green Man pub on the corner. After last orders at ten o’clock every Friday and Saturday a crate of beer would be brought back to the flat and my uncles tinkled on the piano while Mum played the spoons and tap-danced. Everyone sang until the early hours of the morning, Cockney wartime songs such as ‘We’ll Meet Again’, or Irish and Scottish folk ditties like ‘Danny Boy’ or ‘Loch Lomond’. Mum was a brilliant tap dancer; when she was younger she wanted to be like Ginger Rogers and she danced at all the parties. Dad was a burly man who had a lovely big voice and in another life he would have been an opera singer. He used to sing in the bathroom, making the words up. In many ways he was misunderstood because he didn’t often show his feelings – but when something did hit him he’d be in tears with emotion; he felt things deeply.

As a young child, I also loved going out with my grandma, my mum’s mum, who was a fruit-seller. Dolly Dunn was short and well built, and one of my favourite things was to sit balanced on her handcart by the handlebars while she wheeled me up and down the Dock Road shouting ‘Fruit! Fruit!’ It was a great feeling. People would gather round saying, ‘There’s Dolly Dunn, let’s buy our fruit, she’s always got the best.’ She was the real money-earner in the family. From Monday to Saturday she’d get up early and go to the market to buy fruit and vegetables for the handcart, even in winter. On Sundays she sold flowers outside Ford Cemetery, keeping them in bunches in a big basket that she carried on her head. She always had the freshest blooms.

My dad’s side, the McGlory family, were posh because they lived in a terraced house and always seemed to have the best food and nicest clothes. By contrast, Mum and Dad were constantly having to scrimp and save. In the winter, when it snowed, our flat was so cold that there were icicles inside the window, and we huddled round a small fireplace in the living room. Sometimes, Santa Claus didn’t come at Christmas and we just had an orange and an apple each, but there was always Christmas dinner. The size of the turkey depended on how well Grandma Dunn did with her barrow. We would all stand round the table while she brought in the bird, proudly placing it in the centre. It was my mum’s job to pluck the feathers and get it ready. Even though we didn’t get presents, this Christmas dinner made up for everything.

* * *

My mother, Maggie, was tall, thin and very beautiful when she was young, but she had a hard life. My grandpa James Dunn was a docker who came over to Liverpool from Tipperary in Ireland, and my maternal grandparents were from County Louth, near the Northern Irish border. Mum came from a family of ten children who lived down near Liverpool docks, only five of whom survived. In those days bad sanitation, damp housing and poverty in general meant that many children died shortly after birth. At five o’clock every morning Mum and her siblings would go to the railway tracks to pick up coal that had fallen off the steam engines and take it home for fuel. They went to school with dusty hands and were punished for wearing dirty clothes.

The story of how my mum, Maggie Dunn, met my father, Joseph McGlory, is an unusual one. Her first love was actually Joseph’s brother, Richard. At sixteen my mum worked in the British Tobacco factory, and it was there that she met twenty-six-year-old Richard McGlory. They courted and fell deeply in love, but the burgeoning relationship was interrupted by the Second World War, when Richard joined the merchant navy. His younger brother Joseph, my father, insisted on going with him to fight the Germans. Even though Dad was two years below the enlistment age of eighteen, he idolised his brother who arranged false papers so he could join up too. A few weeks after setting off, their ship, the steam tanker SS British Consul, was torpedoed in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and the crew had to stay in the Caribbean for six months while it was repaired. During that time Richard received a letter from Mum saying she was pregnant, expecting his baby.

‘Oh Margaret, please arrange the wedding. As soon as I return we’ll get married,’ he wrote back, telling her to go to his sister Julia for financial help.

But not long after his letter was sent, tragedy struck. On 18 August 1942 my dad was on the night shift but he had a high fever so Richard said, ‘You go to bed, I’ll do your shift.’ Early the next morning the ship was torpedoed again, but this time it hit the engine room and two people died. My dad was rescued but his brother Richard didn’t survive. Dad was haunted by memories of seeing him drown, of sitting in the lifeboat shouting, ‘My brother’s over there!’ long after Richard disappeared beneath the waves. Dad’s name was on the night-shift log when the ship went down, so he was the McGlory brother reported dead. When he returned home the family were at the docks expecting to see Richard. Even though they were glad to see my dad alive, they were devastated that his older brother had died.

Despite Richard’s letter to Mum before his death, the McGlory sisters pretended they knew nothing about his marriage proposal so that they could share the money that was sent to the family in compensation. Forced to have the baby alone, Mum became a single mother at seventeen, living in a poky little house by the docks while the McGlorys, a strong Catholic family, ignored her. Just three months later, baby Winifred died. On the day of the funeral Mum ran behind the glass carriage where her baby lay in a tiny white coffin. ‘Why doesn’t anybody believe me?’ she cried. ‘Everybody says she’s dead, she’s only asleep!’

Mum slowly recovered, finding work in the ammunitions factory, and then on the trams as a ticket collector. My dad was on leave one day when he bumped into her.

‘You’ll never believe who I saw working on a tram as a clippie,’ Joseph said to his sister Julia.

‘Who?’

‘Maggie Dunn.’

Julia turned to her sister Annie and said, ‘We’ve lost him. ’Cos what Maggie Dunn wants, Maggie Dunn gets.’

My dad ended up marrying my mum and, even though he knew she loved him, at the back of his mind there was always the niggling thought that he’d been her second choice. I was their first child, born after the war on 2 February 1946, when much of Liverpool was still a bombsite. We had three bedrooms: Grandma Dolly shared one with my uncle, while I slept with my parents in another, and Grandpa was relegated to the box room.

Grandma was a hard-working woman who rose early with her flower cart and, like many of her friends, slept separately from her husband. People told me that my grandfather was a bit of a dandy, and may have carried on with other women. Wives might have put up with bad behaviour when their children were small, but started paying their men back as they got older. My grandparents’ generation didn’t really get divorced, the husbands and wives would just stop sleeping together.

By the time I was born my grandfather wasn’t working any more. He used to have a job at the docks as a cocky watchman, a security guard, but after he stopped he would just hang around with his friends, and sometimes he would take me along. Many of these men had lost a limb in the First World War, so as a child I assumed getting older meant that a leg or arm would drop off. Grandpa was a dandy with a hat and a blazer. He was seventy-four when he died and I always remember people saying he was still very nifty on his legs. I think he was a good catch in the day.

* * *

When I was two years old my mother had a baby, Bernadette, who died. In the Catholic Church it was considered saintly for a mother to sacrifice her life for her unborn child, and if a priest had been in the hospital that day when the baby got stuck he may have encouraged my mum to become a martyr. But a priest wasn’t around so the doctor decided to save my mother, not the baby, and thank God he did. I’d have been without a mum and the rest of my brothers and sisters wouldn’t have been born. She didn’t tell me what happened until years later. My dad was away at sea, so a neighbour took me to visit the maternity ward, where all the mothers had babies apart from my mum. She was sitting in bed in a posh morning coat she had borrowed, and she was crying. The neighbour tried to comfort her, saying, ‘You’ll be OK, Maggie, there’ll be other ones.’

Our neighbour was right – my first three siblings Joseph, Richard and Margarita arrived in quick succession between 1949 and 1953. Me and my brothers slept top to toe in the big double bed...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Zeitgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-37705-X / 057137705X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-37705-3 / 9780571377053 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 472 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich