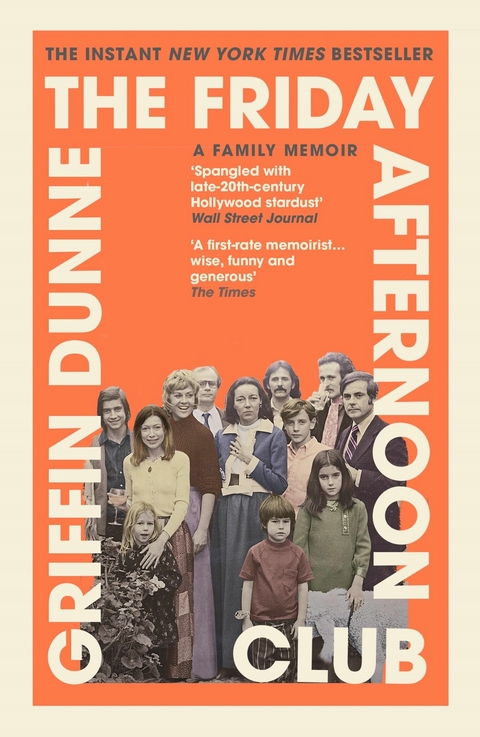

The Friday Afternoon Club (eBook)

400 Seiten

Grove Press UK (Verlag)

978-1-80471-056-2 (ISBN)

Griffin Dunne has been an actor, producer and director since the late 70s. Among his work, he produced and acted in After Hours, directed Practical Magic and the documentary The Center Will Not Hold about his aunt, Joan Didion. Griffin and his dog Mary live in the East Village of Manhattan.

Griffin Dunne has been an actor, producer and director since the late 70s. Among his work, he produced and acted in After Hours, directed Practical Magic and the documentary The Center Will Not Hold about his aunt, Joan Didion. Griffin and his dog Mary live in the East Village of Manhattan.

One

My mother was the only child of a cattle rancher. Her father’s thirty-thousand-acre ranch was called the Yerba Buena, situated in Nogales, Arizona, a border town just north of Sonora. Tom Griffin chose to raise Santa Gertrudis cattle, a risky venture for a city slicker from Chicago, but at last he’d fulfilled his dream to return to Arizona’s high desert, where as a child he was sent to cure his weak lungs.

Tom was born into a socially prominent family that had made its fortune in the Griffin Wheel Company, which manufactured wheels for all the Pullman train cars that crossed America. His uncles were playboys and philanderers whose shenanigans often found their way into the gossip columns of the Chicago dailies. In the mid-1920s, my great-great-uncle George Griffin died of a heart attack while in bed with his mistress aboard his yacht off the coast of Palm Beach, Florida. The mistress was Rose Davies, sister of the movie star Marion Davies, who happened to be the mistress of the publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst, so elaborate measures were taken to prevent a national scandal. Ms. Davies was snuck ashore in the dead of night and caught the next sleeper car to Los Angeles, with actual Griffin wheels whirling beneath her berth. Meanwhile, George Griffin’s steadfast crew dressed him in pajamas, loaded him onto a tender, and checked his corpse into the Breakers Hotel. After tucking him in, the vice president of the Griffin Wheel Company solemnly called George’s wife to say that her husband had just died peacefully in his sleep.

His wife, my great-great-aunt Helen Prindeville Griffin was no stranger to wealth, having been a doyenne of Washington, DC, society who summered in Newport, Rhode Island. At the moment when Mrs. Griffin had been notified of her husband’s death, she was in bed with her lover at the Hotel del Coronado in California, and took the news that she was a widow rather well. She untwined herself from the arms of Admiral Paul Henry Bastedo who served under Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt, and proposed they get married in the morning so he could be her date at her late husband’s funeral. To the tabloids’ delight, the newlyweds took Helen Prindeville Griffin Bastedo’s private railway car to Lake Forest, Illinois, to attend the service. The act so outraged the Griffin family that they used their juice with Union Pacific to divert the train and the unlucky passengers coupled to Helen’s private car. The train choo-chooed deep into Wisconsin, denying the newlyweds their grand entrance to the funeral. The family were less successful trying to have Helen cut from George Griffin’s will, and she inherited every cent of his enormous fortune.

Scandal visited the next generation of Griffins a decade later, on the day of Tom’s wedding to a woman from an equally prominent family. Approaching the church in the back of a limousine, he watched the crowd of guests and photographers awaiting his arrival and told the chauffeur to keep driving, all the way to Chicago Union Station. Once there—still in top hat and tails—he boarded a Pullman car (on Griffin wheels) and headed westward to begin his new life as a rancher in Nogales.

AS KIDS, we loved when Mom took us to Nogales. My younger brother and sister and I used to cross the border into Mexico on foot with a pack of cousins, as easily as going through a subway turnstile. We rambled up a hill to reach a restaurant called La Roca, set on top of a large rock. At the bottom of the rock, a cave, once a prison, used to shelter a cantina called La Caverna. La Roca was built above only when La Caverna burned down under suspicious circumstances. Tom Griffin was long dead by then and was spared the demise of his favorite haunt, where he famously sat at his usual table, with a parrot on his shoulder who’d bite anyone who got too close. As much as he tried, he never mastered Spanish as well as his parrot, but he made up colorful words that sounded like the language, and locals always got the gist.

One of my grandfather’s favorite requests was for the mariachis to play “El ternero perdido,” or “The Lost Calf.” The song required the alto trumpeter to go outside the bar and way down the block, to toot his horn as the lost calf. A chorus of mariachis sang as the worried cows calling out for their lost calf, and then there was a solo, presumably the mother of the calf, who pleaded, “Oh where, oh where is my little lost calf?” The tension would build, and suddenly the audience would hear the lost calf somewhere far off. His trumpet sounded like a child, crying for its mother. When the patrons of La Caverna heard the lost calf, they’d go apeshit and Tom’s parrot would squawk at the top of its tiny lungs. Then the door would burst open and the alto trumpeter would wail, “I’m here, I’m here, I found you at last.” Everyone in the bar, drunk on tequila and elated that the little calf had finally found its mother, would cry in relief.

On one trip to La Roca, everyone danced on top of the rock that once housed La Caverna. Mom tried to stump the mariachis, knowing the lyrics to every cancion, which impressed the band, though they were never stumped. My little sister, Dominique, started to yawn around two in the morning, and Mom took the hint and gathered us to cross back over the border. When the mariachis saw that Mom was leaving, they begged her to stay a little longer. One of our cousins said in Spanish to the musicians, “Why don’t you guys come with us?”

We went back through the turnstiles into the United States, no questions asked, followed by the mariachis, who had to lift their giant guitarróns over the twirling bars. Our group marched on to my cousin Eddie Holler’s house, where we were staying, just across the border.

Mom put us to bed when we got there, and somehow we managed to sleep through the ruckus downstairs. Early, but not too early, the next morning, I went downstairs for something to eat and stepped over mariachis asleep on the floor, still in sombreros, clutching their trumpets and harps.

ONE LATE NIGHT in Los Angeles, in my early teens, I was watching a movie on television with my mother, as we often did back then when Alex and Dominique were asleep.

On the screen was an old Western about settlers traveling the frontier in wagon trains. They were under such constant attack from Sioux warriors that one of the homesteaders went mad, leapt from the wagon, and shrieked across the plains. His wife, not missing a beat, calmly took over the reins and snapped the horse along to keep up with the train. “That woman,” my mother said to me in the glow of the television screen, “is exactly like your grandmother.”

My mother, Ellen Beatriz Griffin, was given the middle name of her mother, Beatriz Sandoval. My grandmother—Gammer, as we called her—was one tough cookie. It was said that she’d been stung so many times by scorpions that she was immune to their pain.

The Sandoval family had been in Mexico for over two hundred years and were raised to consider themselves Mexicans, not Spaniards. Beatriz’s grandfather, José Sandoval, owned silver mines, fishing and pearl concessions in the Sea of Cortez, and major real estate in Hermosillo and Guaymas. The Sandovals were on the wrong side of the Mexican Revolution, so as the rebels closed in to seize their property, my relatives fled to the safety of Baja California, before eventually settling in Nogales, and in time managed to build their fortune all over again.

Beatriz’s family was not without scandal either; her brother Alfredo did serious time in prison, not once but twice, for embezzling from a bank the Sandovals owned. His grandfather forgave him the first time, but after the second he demanded that Alfredo’s name never be mentioned, an order Beatriz followed to the end of her life. I was perversely proud to have a jailbird in the family and tortured my grandmother with my curiosity about him, oblivious that her shame was on par with being the sister of John Wilkes Booth. My mother finally pulled me aside and told me to knock it off.

Tom Griffin met Beatriz shortly after moving to Nogales and swept her off her feet, even though she was engaged to an aristocrat from Mexico City. Tom courted and badgered her to dump her fiancé and marry him instead, and after she gave in to his charms, they soon eloped. However, her previous intended was already on an overnight train from Mexico City to Nogales for their wedding, so to be sure he didn’t arrive, Beatriz sent a telegram to every stop the train would make—and there were many in those days—to inform him that the marriage was off.

PLEASE DO NOT COME. STOP read the first message he received as the train was pulling out of San Juan del Rio. THE MARRIAGE IS OFF. STOP. By Zacatecas he held twelve more. I PLAN TO MARRY THOMAS GRIFFIN. STOP. At Hermosillo, Señor Sad Sack had a neat pile of about thirty telegrams before finally taking the hint and turning back to Mexico City.

Though my mother romanticized her parents’ relationship, she was a lonely child on the Yerba Buena, pained by her father’s absence during World War II, when he served in the Pacific as a captain in the navy. She once told me, after one too many Pinot Grigios, that when she was a little girl, she walked into her parents’ bedroom and thought her father had come home because an officer’s uniform was crumpled at the foot of the bed. Gammer shrieked in alarm as her daughter slipped out of the room, neither...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater | |

| Schlagworte | After Hours • An American Werewolf in London • Carrie Fisher • celebrity memoir • Charles Manson • dominick dunne • Dominique Dunne • Hollywood • Hollywood memoir • Joan Didion • Martin Scorsese • New York • Poltergeist • practical magic • Summer of Love • This is Us |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80471-056-3 / 1804710563 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80471-056-2 / 9781804710562 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich