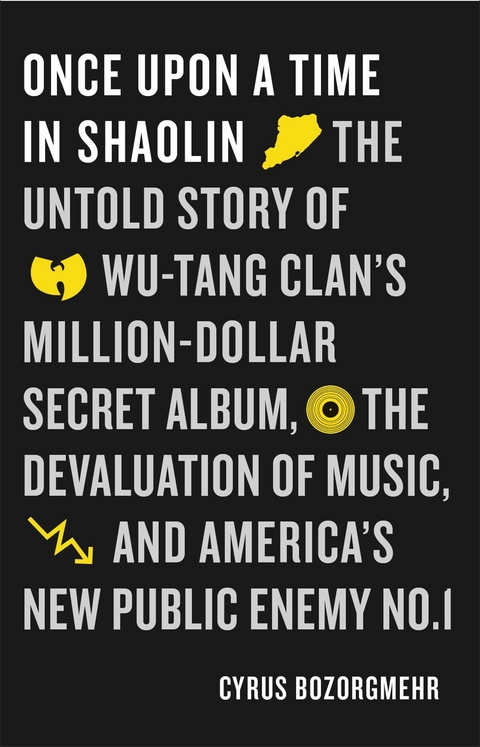

Once Upon a Time in Shaolin (eBook)

232 Seiten

Jacaranda Books (Verlag)

978-1-909762-66-4 (ISBN)

Cyrus Bozorgmehr was the senior adviser on the Once Upon a Time in Shaolin project and worked alongside Wu-Tang Clan's RZA and producer Cilvaringz. He is also part of the Arcadia Spectacular, a British performance and entertainment collective based in Bristol and winners of the Mind-Blowing Spectacles Award. Born in England, he now lives in Marrakech, Morocco.

Cyrus Bozorgmehr was the senior adviser on the Once Upon a Time in Shaolin project and worked alongside Wu-Tang Clan's RZA and producer Cilvaringz. He is also part of the Arcadia Spectacular, a British performance and entertainment collective based in Bristol and winners of the Mind-Blowing Spectacles Award. Born in England, he now lives in Marrakech, Morocco.

2007

“Have you ever heard of the Wu-Tang Clan?” Well, of course I had. Didn’t explain what the fuck this rather placid-looking Moroccan chap in glasses had to do with them though. Maybe he ran the local fan chapter.

“That’s my crew—I’m part of the extended Clan. Name’s Tarik.”

This dude’s going to try and sell me a villa next. It was just too ludicrous to contemplate. I smiled and nodded indulgently. But there was something about the way he’d dropped it. No big thing—didn’t oversell it, no preening or fluffing of feathers. He was either one seriously left-field motherfucker or a gloriously incompetent bullshit artist. Only time and a Google search would tell. And yet, as the conversation took its flow, something sparked under an African sky.

We had been introduced at a lunch party hosted by the sculptor and author Jimmy Boyle on a crystal-clear day in Marrakech. Despite my suspicions that Tarik might be insane or at least a dangerous fantasist, we were rolling deep within minutes. By sundown, we had set the music world to rights and he still hadn’t had a sip from the vine, while I was about three bottles to the good. A set of supremely ephemeral breakthroughs on a warm spring breeze.

And then what seemed like the most absurd of all the ideas floated.

“I’ve been thinking about a single copy of an album, sold privately,” said my new friend.

“Sounds dangerously elitist,” I replied... even if you could argue that it was an evolutionary adaptation generated by the economic meltdown within music.

The much-heralded democratisation of the digital had, like so many revolutions before it, morphed into a new tyranny. Recorded music was increasingly viewed as worthless, and getting heard was more difficult than ever as the ease of production and digital distribution created a new enemy—saturation. Independents were buckling, development budgets were a distant memory, and perhaps most worrying of all, the perception of music had shifted into something between voracious consumerism and a God-given right.

But commodifying music even further and placing it squarely in the hands of the wealthy? That was a step too far for me.

We said our goodbyes without any exchange of numbers or gushing promises—but it had been an intriguing conversation. Still needed to do that Google search, though.

And there it was... Wu-Tang-affiliated producer and rapper Cilvaringz. Well, fuck me...

2009

There’s nowhere on this earth quite like Marrakech. Cast from the sands of a thousand years, her pockmarked battlements sigh cheerfully through the ravages of time. Labyrinths burrow into shadows of still reflection, pause for a quick cup of tea, and then dance the rhythms of lusty commerce. Tucked behind the veil, shady courtyards envelop themselves in the sweet scent of orange blossom, while out in the thoroughfares, an indulgent chaos reigns by popular acclaim. And away in the distance, the cloud-capped majesty of the Atlas Mountains nods sagely through the ages as horns blast, motorbikes chug in dissonant song, and tribal drums ring out the chant.

Marrakech’s reputation for bohemianism is both thoroughly merited and eloquently contrived—much like bohemianism anywhere. Naturally there was a sense of privilege to anything quite so theatrically self-aware, but the first wave of flamboyant creatives who forged its reputation were gorgeously genuine. Crushed velvet capes and eccentric old aristocrats, barking mad painters and tragic diplomats tripped the oriental fantastic, and before you knew it, Marrakech was a byword for cosmopolitan style, a caravanserai for the international aesthete.

I had been here on and off now for three years. I travelled extensively for projects of all stripes and saw Marrakech as something of a refuge from my own mischief. I behaved here, nurturing a normal existence rather than staying awake for days on the jagged edge of pressure like I invariably did on a mission. While reveling in the town’s joyous innocence, I clung to the contemplative life, preferring to wake at dawn to get some work done in a cloistered silence, but as a result, I had acquired hermit status in the social calendar. My long-suffering wife was less than impressed, especially when photos of me clearly having the time of my life kept popping up to document the jobs I’d been on, so when she suggested we engage in some vaguely meaningful way with Marrakech’s impending art biennale, I felt I was a “fuck that” away from divorce.

The Marrakech Biennale’s remit seemed to be assembling a mix of local and international art in a series of locations around the city, from crumbling palaces to exclusive boutique hotels. The opening cocktail party offered little hope for a visceral cultural experience; it felt like someone had satirised an artsy circle jerk in Chelsea, transplanted it to a palm-strewn rooftop, and used the local populace as an abstract string to a bullshit bow. But that wasn’t a fair impression of the event as a whole, and as the days unfolded, we attended a range of exhibitions, installations, and talks, many of which were undoubtedly positive for the city’s cultural life. There was perhaps more talk than evidence of cross-cultural engagement, and despite there being Moroccan art for Western collectors and Western art for Moroccan collectors, it did at times feel that there was largely fuck-all for the average Moroccan bar a couple of headline street pieces. It was one of those things that started off with the best of intentions but accidentally ended up elitist because it just couldn’t stem its own tide.

Having been to a series of talks by Moroccan authors and film-makers, I found myself trudging toward the Bahia Palace, one of the major exhibition centres, with my good mate Nick, and as we approached the entrance, who should we bump into? Yep—you guessed it. Cilvaringz and his wife, Clare.

We were delighted to see one another despite having made absolutely no effort in the intervening three years to get together for a drink or something, like normal people would. But the kind of connections that feel totally natural after three years and one intense conversation are far more valuable than vats of synthetic small talk, and I knew instantly that whether the art was transcendental or reminiscent of a 1970s novelty store, we were going to have some fun.

Cilvaringz was on the board of the Biennale, and as we strolled around the palace, he grew increasingly frustrated at the kind of money that had gone into the more forgettable exhibits. From buckets to paper planes to a couple of old bed frames, it threw up an instant mirror to the increasingly tortured state of music.

Grabbing a coffee afterward, we settled in for a postmortem. It wasn’t that we were buying into the inverted snobbery of needing art to be figurative or the old “my six-year-old could do better” chestnut. Testing boundaries and the kaleidoscope of perception was what contemporary art was all about—be it a monochrome canvas or a pile of industrial rubble. But the line between high concept and complete bollocks was fraying, and this wasn’t saying anything new. It was just really, really—mediocre.

And while buckets were selling for five figures, an ever-diminishing pool of people was prepared to pay for music. For albums that take years to make and have every ounce of a musician’s heart and soul in them.

What was it that gave someone the barefaced balls to sell paper planes for thousands, while a new song gets ninety-nine cents at best and more likely gets torn out of the torrentsphere?

The ninety-nine-cent price tag was about volume, of course. The music industry model was always based on two main foundations—mass production and egalitarianism. An artist sells one original piece, or limited-edition prints, but a musician can sell millions of units. All of them are affordable, and outside of rare editions, everyone has a shot at buying them with no-one paying more or less than anyone else.

But that was the architecture of the predigital world. A world in which people would grow increasingly excited as an album release date approached; where they rushed down to the record store and queued alongside others they shared a community with. And then glided home on a high, lovingly unwrapped their album, read the sleeve notes, listened for months, soundtracked highs and lows, vibrant peaks and calamitous troughs, and then mounted it on a shelf as an expression of identity. In other words, they treated it like art.

There was a pilgrimage to the acquisition of new music—even if it was two blocks away at Tower Records. And the emotional and financial investment people poured into music was relative to their experience of it, at least in some way. Tragically, in a weird evolutionary flaw, the less effort people have to make for something, the less they value it. And while that investment doesn’t have to be economic—if you run twenty miles for an album, or do a hundred push-ups for a single, that’s still you infusing an end product with a sacrifice. In the modern age, that sacrifice is almost always represented by money, so does placing economic value on something directly affect how we experience it? That’s a very uncomfortable question.

Cilvaringz was getting increasingly animated. The table was taking the brunt of it. “People don’t see music as art anymore. They don’t see it as something valuable. That has to change, and right now—I might just be working on a project with RZA that I hope will start...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.10.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Pop / Rock | |

| Schlagworte | Cappadonna • East Coast • Ghostface Killah • GZA • Hip-Hop • Inspectah Deck • Masta Killa • Method Man • music • Music Industry • Non-fiction • Ol' Dirty Bastard • Oral History • Raekwon • RZA • secret album • shkreli • U-God • Wu-Tang Clan |

| ISBN-10 | 1-909762-66-0 / 1909762660 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-909762-66-4 / 9781909762664 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 608 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich