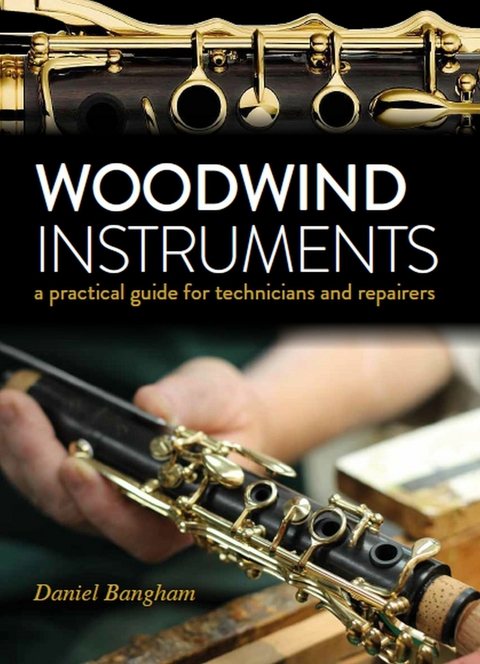

Woodwind Instruments (eBook)

256 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4030-2 (ISBN)

Daniel Bangham has been a woodwind technician, repairing and hand-making clarinets for over forty years. After training at Newark Technical College, he left to set up a repair business in Cambridge at the suggestion of Nicholas Shackleton, who wanted help looking after his collection of historic clarinets. A few years later, once the repair business was established, Daniel was invited back to Newark to become the visiting lecturer where he found his love for teaching. By the 1990s he was making instruments for international performers and his work featured as solo instruments on acclaimed recordings. He was also consulting for a number of other manufacturers, as well as managing his repair and retail shop called Woodwind & Reed. In the early 2000s Daniel set up a teaching workshop called Cambridge Woodwind Makers. This workshop gives a venue for visiting specialists to teach their specialist skills to students, who come from around the world.

CHAPTER 1

Initial Dismantle and Reassemble of an Instrument

I am going to start by describing how you can start your repair journey through dismantling and re-assembling an instrument. At this stage you will be identifying problems as you go, but not necessarily fixing them.

Whatever instrument you want to focus on later, I suggest you start by working on clarinets. The skills needed for a clarinet are transferable to other instruments. For your very first attempt, I suggest you use a low-value clarinet, one you can afford to make mistakes on. As soon as you feel confident, use better instruments, ones that are already in good condition. That way you can get familiar with what an instrument should look and feel like, without getting distracted or side-tracked with problems. It is by handling good instruments that we learn what we are trying to achieve.

Basic tools

I remember when I first started my training, I felt overwhelmed by all the unfamiliar tools and equipment. But when it came to the first day of teaching, we started with the basics: a workbench, four hand tools and a few old instruments to take apart and put together. The idea was that we needed to get first-hand experience of dismantling the instruments before we could really understand the study material we were going to cover over the next few years. I am taking a similar approach. You don’t really need to know all the names of the parts or the tools to be able to take it apart and put it together again. Just give it a go. (I will refer to parts of the instrument and processes you might not be familiar with at this stage; please look at the relevant chapters later in the book if you are unclear what I mean.)

Workbench

If you don’t have a dedicated workbench already, create a temporary workbench from a sheet of plywood, with an apron screwed on the front that can hook over the side of an existing table. Add a bench peg to this and you’re all set!

Fig. 1.1 Improvised workbench.

A bench peg is traditionally a piece of hardwood turned on a lathe into a cone. Though this is the preferred shape, there is no reason not to make several pegs in a row, with dowelling of different diameters. They need to stick out about 15mm and be smaller than the bore diameter of the instruments you are working on.

Shaving brush

I have not found any other brush to give the instrument an initial brush down and clean that works better than a shaving brush. The density and stiffness of the bristles are perfect and there is no metallic collar that might scratch the instrument.

Fig. 1.2 Shaving brush.

Screwdrivers

Your choice of screwdriver will be governed by what instruments you will be working on. Different instruments require different sized screwdrivers. The width of the blade needs to match the diameter of the screws you encounter. This is to ensure you do not damage the screw head or the surrounding pillar. The screwdriver blade should be just under the width of the screw head (maybe 0.1 or 0.5mm).

Fig. 1.3 Screwdrivers in three sizes.

Useful blade widths are:

1.95mm for clarinets, oboes and flutes

3mm for saxophones

1.7mm for adjusting screws

The screwdrivers should have long shafts, which will give you better access to screws deep in the keywork. My best screwdrivers have a shaft 150mm long and the handle is another 90mm long (total 240mm) with a 1.95mm and 3mm blade width.

Fig. 1.4 A screwdriver with a long shaft allows you to get to screws deep in the keywork. Notice that I am steadying the tip of the blade with my thumb.

My screwdriver with a 1.7mm tip has a 50mm shaft and 90mm handle. The long shaft allows me to align the screwdriver on the same axis as the screw, even when the key is located well down the instrument’s body.

Fig. 1.5 A 2mm wide blade will only engage with the screw slot if it is perfectly in line with the axle.

Fig. 1.6 It will not engage completely if approached at an angle.

Fig. 1.7 A 1.95mm blade that has a parallel shaft will get very good engagement with the slot even when inside the pillar.

Fig. 1.8 This tapered ground blade will engage, but there is much less contact area in the slot so you risk damaging the hinge screw.

Good screwdrivers of the right width for our industry can be hard to find. Until you have found or made your perfect screwdriver, I suggest you look at the tools used by the electronics industry, as they have screwdrivers with long shafts and 2mm wide blades. You will then need to use a diamond file, grindstone, or grind wheel to make the blade a tiny bit narrower. Figs 1.5 to 1.8 show how the width and shape of the blade affect how well the blade will engage with the slot in the screw as it goes inside the pillar.

I recommend that you have a shallow domed swivel end to the handle; this allows you to push hard against the screw head at the same time as rotating the blade easily. If you don’t have a swivel handle, try to retrofit one.

Other factors that affect a screwdriver are the diameter of the handle (this changes the leverage you can apply and speed at which you can spin the screwdriver), the quality of steel used and the tempering it is given.

You can make your own screwdriver, from silver steel, or high-speed steel (HSS) drill stock.

Fig. 1.9 The tip of one of my favourite screwdrivers.

Many screwdrivers offered for sale by specialist suppliers are susceptible to chipping on old and stuck screws. I have been very happy with the straight tapered wedge shape of the Kraus screwdrivers (Kraus tools are no longer available to purchase new, but it is worth seeking out second-hand Kraus tools as there are currently no manufacturers making specialist tools of this quality). The shaft of these screwdrivers is 4mm in diameter, and 5mm from the end, the diameter reduces to the blade width (Fig. 1.9). This gives the blade extra stiffness that significantly reduces the torsional and longitudinal flex.

Spring hooks

My two favourite spring hooks have a groove on the top end of the shaft; this makes it easier to manipulate the spring in difficult-to-access spaces.

Fig. 1.10 My two favourite spring hooks: one made by Music Medic (top); the other I made myself.

Fig. 1.11 At the end of the spring hook (left) is a groove that can engage with a spring (right). This allows you to push the spring through narrow gaps.

Fig. 1.12 I was sent this spring hook by Pearl Flutes many years ago. It is made from a large sewing needle with the eye heated, bent into a hook and the eye opened up to create the pushing slot. The needle is then held in a pin vice.

I recommend you make your own very narrow hook and pusher for working on clarinets and oboes. You need to be able to remove the hook from between the spring and the hinge tube when the gap is very narrow. The spring hook will need to be made from carbon steel, correctly hardened and tempered.

Pliers

Pliers are good for manipulating or bending keys when on the instrument. I have two or three sizes and styles of these, ranging from 30mm-long blades of 6mm width to 50mm long by 8mm wide. The blade thickness is very narrow, which is an important design feature.

Fig. 1.13 Smooth jaw duckbill pliers.

Fig. 1.14 Maun parallel-action pliers.

Fig. 1.15 This is the Knipex parallel acting pliers; model 86 03 150, modified by Music Medic.

Fig. 1.16 This snipe-nosed variant of the parallel-action pliers (the smooth jaws narrow to a point) is excellent for holding key arms.

The jaws on these pliers must be smooth; this prevents unnecessary damage to the surface you are holding. Parallel pliers should be the only pliers you use to grip hinge screws when removing keywork. They are useful for key bending and straightening. There are two types that I use: Maun Industries make the original and, in my opinion, best. I have two sizes: 140mm and 180mm (Fig. 1.14).

You can modify off-the-shelf pliers with a belt grinder.

Brushes

I have acquired a number of brushes over the years for cleaning out tone holes and small tubes.

Fig. 1.17 Tone hole cleaning brushes.

All-purpose materials

Removable putty (Blu Tack)

This is a common material in the UK, but not so common in other countries. It is a soft putty that is designed to attach posters or pictures to walls and other hard surfaces. It acts as an adhesive but doesn’t leave a residue when removed. I use it to temporarily seal tone holes when testing for leaks. I knead it for a while before pressing it over the hole. It leaves a clean surface.

Fig. 1.18 Blu Tack other brands are available, e.g. Poster Putty, Power Tack, Sticky Tack.

Cork

The choice of dimension of cork to purchase depends on the instruments you are going to work on. In general, you will need wafer cork, and 1mm, 1.2mm, 1.4mm, 1.6mm sheet cork. The standard sheet size is 150 × 200mm. Bassoon repairers should try and get hold of the larger 12 × 4in size of sheet cork as you need the extra length to use on the bottom tenon joints.

Fig. 1.19 Using a wine cork as a source of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.9.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Instrumentenkunde |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Instrumentenunterrricht | |

| Schlagworte | Bassoon • bed plates • Broken • Cambridge Woodwind Makers • Clarinet • fix • Flute • Instrument • Keys • MEND • needle springs • Newark Technical College • Notes • Oboe • Octave • Pillars • point screws • Repair • saxophone • silver soldering • tenon joints • tenons and sockets • tone hole rims • tone holes • Woodwind • Woodwind & Reed • Workbench • Yamaha |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4030-9 / 0719840309 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4030-2 / 9780719840302 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 49,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich