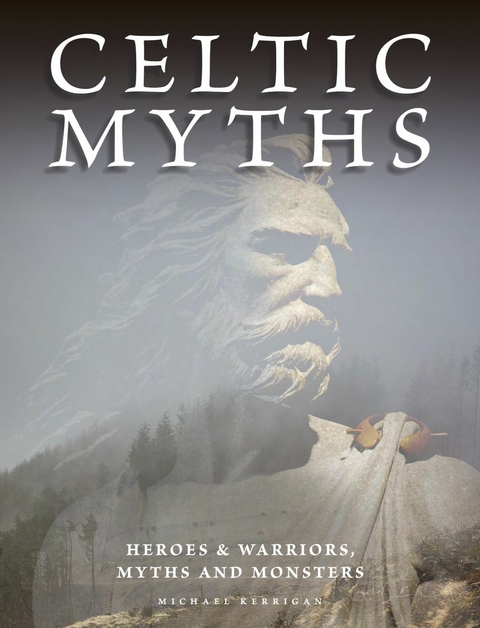

Celtic Myths (eBook)

224 Seiten

Amber Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78274-339-2 (ISBN)

From around 750BC to 12BC, the Celts were the most powerful people in central and northern Europe. With the expansion of the Roman Empire and the later Christianization of these lands, they were pushed to the fringes of north-western Spain, France and the British Isles. But there the mythology of these peoples held strong.

The tales from Celtic myth were noted down and also absorbed into other cultures. From Roman and Christian scribes we know of characters like Morrigan the shape-shifting queen, who could change herself from a crow to a wolf, Cu Chulainn, who, mortally wounded in battle, tied himself with his own intestines to a rock so that he'd die standing up, and the Cauldron of Bran, which could restore life.

Other than being fascinating in their own right, Celtic legends are of interest for the influence they had over subsequent mythologies. The story of the Holy Grail first appears in medieval romances but its antecedents can be found in the Celtic tale, the Mabinogion.

Illustrated with more than 180 colour and black-and-white artworks and photographs and maps, Celtic Legends is an expertly written account of the mythological tales that both fascinate us and influence other writings.

The gods and monsters, warriors and legends of Celtic mythology Spanning the whole of the Celtic world from Spain to the British Isles Includes 180 photographs, maps and artworks

The monastery of Clonmacnoise (Cluain Mhic Nóis in Irish, meaning “Meadow of the Sons of Nós”) was founded in 544. Celtic art was to become inextricably associated with Christian symbolism – but the early Celts followed a very different creed.

1

THE CELTIC COSMOS

Classical commentators were struck by the centrality of “religious observance” in Celtic life; at the same time they struggled to understand a creed without written scriptures, graven images or constructed shrines.

A mantle of mist shut out the sky above; below, a buffeting wind picked up great squalls of rain and scourged the slopes, their green, scabby grass, their tawny bracken bending to the blast. To the frightened wayfarers watching from the ridge, the hillside seemed quite bleak enough but further down a dismal prospect gave way to one of grotesque revulsion and fear. Covering the valley bottom, curving over like the carapace of a vast and squirming beetle, glossy black shapes jostled and crowded in a hectic throng. A mob of ravens, they draped the ground in deathly black, but, as they frantically pushed and pecked, the viewer caught glimpses of grey, white, gold, bronze and red between their writhing forms. Only by gradual degrees did it become clear to the dismayed onlookers that this gruesome kaleidoscope of colour represented what had been a battlefield. That mass of mangled mail, of pallid flesh, of gaping wounds, of contorted limbs, was all that remained of the youth of Ulster, cruelly slain.

As for the flapping, croaking, clawing birds climbing over one another in their greed for the broken bodies beneath, there was never any doubt in the viewers’ minds of what they were. The raven was the emblem (for the want of a better word) of the Morrigan, the war goddess – although it represented her in a way that went well beyond religious symbolism or poetic metaphor. The relation encompassed both those things, though, for the Morrigan was at once a bird and a woman; an imaginative principle and a violent, destructive force. (And, at the same time, a creative one – for death had its place in the cycle of life; dead carrion became living, breeding flesh in the body of the raven, so the Morrigan was also a powerful goddess of fertility and enduring life.) Simultaneously unique and manifold, she could be a single raven tracking its solitary way across the sky above a raging battlefield, a bird of the ultimate ill omen, or – as here – a flock of flesh-eating, bone-stripping scavengers. Numbers don’t seem to have signified too much to a cheerfully polytheistic pagan tradition: in some accounts the Morrigan is the Morrigna, a trio (a trinity, even) of bloodthirsty, shape-shifting sisters. Badb, Macha and Nemain too are typically represented as ravens or as carrion crows; again, their names vary according to different local traditions.

The Romans didn’t begin to understand the druids’ religious practices, but they feared their influence over the Celtic Gauls.

Pagan Paradoxes

“The whole nation of the Gauls is greatly devoted to religious observances,” Julius Caesar noted – but these observances didn’t necessarily have much to do with those of Rome or, still less, our own. Many people in the present day make claims to have espoused a “Celtic” spirituality: the reality is that the day-to-day workings of Celtic religion remain obscure. The multifaceted Morrigan is a case in point: words like “goddess” or “deity” barely begin to do her justice, so complex and so elusive is her essential nature. And she was only one of many scores or even hundreds of other deities, many of whom remain embodied in enduring myths. Hence the importance of the druids or priests who not only knew which gods to placate and by what sacrifices, but when to plant and harvest, and when to hunt. They also had a more social function as doctors, advisors and judges in disputes. The Romans distrusted them severely on this account, seeing them as a source of instability. That Roman writers have been our chief source of information on the druids’ activities is decidedly unfortunate, therefore, although one of their most seemingly extravagant charges against these Celtic priests – that they offered human sacrifices at their midnight gatherings – appears to be endorsed by the imagery on the Gundestrup Cauldron.

Armed warriors parade across one side of the sumptuous Gundestrup Cauldron; to the left a human sacrifice is made.

WORDS LIKE “GODDESS” OR “DEITY” BARELY DO HER JUSTICE.

The intricacies of Celtic craftwork are illustrated here on the cover of the Book of Kells.

The picture is complicated still further for us in the present day by the fact that, if they ever really were a single people, the Celts soon ceased to be as they spread out across Europe, while in later times their hold-out territories were inevitably isolated and far-flung. The Morrigan, for example, is an important figure from Irish legend – although she has her equivalents in the mythic traditions of other Celtic regions. Some 2000 years ago, when our opening scene was set, her origins were already long since lost in antiquity. Her very name was ancient, derived from that same Indo-European tradition in which almost all modern European and near-eastern languages – not just the Celtic ones – find a common root. Its first syllable came recognizably from the word mer (or “death” – from which, of course, we get the French word “mort” and the English “mortality”); its second from reg (to “lead”; to “rule” – hence “direct” or “reign”, the Spanish rey or “king” or the French regime).

Then too there’s the fact that in the absence of any written record of their own, the Celts left their oral traditions at the mercy of a posterity that – inevitably – had its own perspectives and its own prejudices. That writing was for centuries the sole property of Christian monks did nothing to clarify the picture: they naturally came at Celtic lore from their own – obviously less than sympathetic – standpoint. To take the Morrigan as our example again, it is ironic that all we know of her has come to us from texts written down by scribes for whom she was nothing more than a monstrous fiction, a scary story.

LET THERE BE LIGHT

It is ironic that a pagan Celtic culture should have found some of its most eloquent expression in a series of carefully crafted Christian texts. For the stunningly colourful illuminated manuscripts made by monks in the religious houses of medieval Europe may be seen as a final (posthumous, even) flowering of the La Tène culture. From early works such as the Lindisfarne Gospels (see right) and the Book of Kells through to the high-medieval Books of Hours, the influence of Celtic craftwork can be traced. Those extravagantly ornate colophons, these riotously swirling vegetal patterns and what are now known as “Celtic knots”: illuminated manuscripts overflow with ornamentation in the Celtic way.

If, in the person of Christ, according to the Gospel, “the Word was made flesh” (John 1, 14), those same scriptures made words the embodiments of Christ Our Lord. And, to heap one paradox on top of another, the religious scribes harnessed the aesthetic conventions of a culture that had consciously rejected literacy (and specifically on religious grounds) to help them convey the mystic rapture that they felt in the expression of their faith.

The Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 700) are a masterwork of Celtic art, a pagan aesthetic pressed into Christian service.

Irish Inclinations

A further fact we need to bear in mind when considering the Celtic inheritance transmitted to us by medieval monks is the bias this has meant towards the heritage of Ireland specifically and, to a lesser extent, that of the Scottish Highlands and Islands and of Wales. For, if the expansion of the Roman Empire had forced the Celts and their distinctive way of life out to Europe’s farthest margins, the implosion of that empire in the middle of the first millennium – and the irruption of barbarian invaders that immediately followed this collapse – forced monastic culture to find sanctuary in the wildest corners of the west. Monks took refuge on rock-bound coastal promontories or on the remotest offshore islands where they would be safe – at least until the onset of the Viking raids at the very end of the eighth century. So, while the Celts must have left an important cultural legacy in central Europe, Gaul and Spain, it was only in the offshore islands that the skills and facilities existed for their learning and their literature to be recorded. This book’s bias towards the Irish inheritance is, accordingly, in some ways unrepresentative – but it’s the inevitable consequence of European history.

ANIMADVERSIONS

What theological scholars know as “animism” – because it attributes anima (the Latin for “life” or “spirit”) to many or all natural objects – was once central to most religious belief around the world. Over millennia, it was to make way for the worship of smaller groups of more powerful but consequently more abstract and less locally-rooted deities – like those of Greece (although their association with the heights of Mount Olympus itself...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.2.2016 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Histories | Histories |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Altertum / Antike | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Weitere Religionen | |

| Schlagworte | celt • Cross • Culture • fen • Folklore • France • Ireland • Legend • Myth • Pagan • Ulster • Wales |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78274-339-1 / 1782743391 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78274-339-2 / 9781782743392 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich