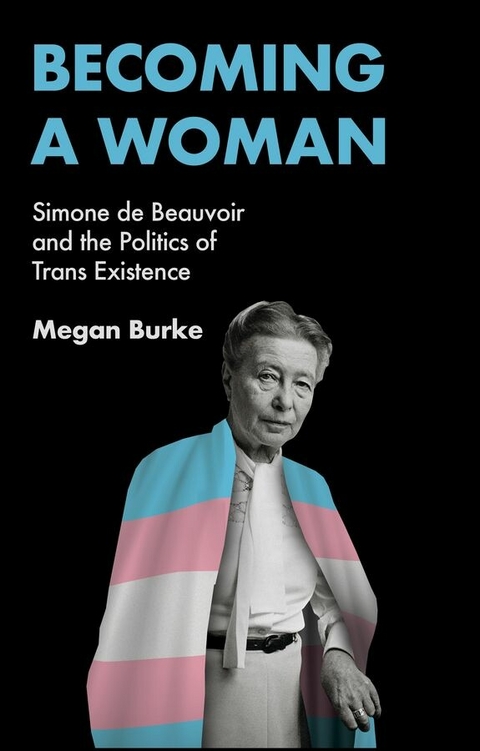

Becoming a Woman (eBook)

138 Seiten

Polity Press (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6200-8 (ISBN)

Megan Burke is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Sonoma State University and the author of When Time Warps.

This highly engaging analysis of the contemporary, global social and political landscape of trans antagonisms draws specific attention to "e;gender-critical"e; mobilizations of Simone de Beauvoir's account of becoming a woman in The Second Sex to advance and justify trans exclusionary positions. Through a careful examination and application of Beauvoir's philosophical and political commitments, Becoming a Woman compellingly explores the significance of her notion of becoming as not only affirmative of trans women, but also as an ethical demand to affirm trans possibilities. More than a reply to gender-critical readings of Beauvoir, this book develops an original, Beauvoirian ethics of gender affirmation offering that show why we ought to challenge trans exclusion and anti-trans movements.

1

Becoming a Woman

When my mom gave birth to me, she didn’t know how the doctor would categorize me. She didn’t know if on the crib in the hospital nursery there would be a celebratory sign marking me as a girl or as a boy. She didn’t know what information would populate my birth certificate. In the early 1980s in the United States, advanced ultrasound technology wasn’t widely available, so the pressure “to know” what genitalia I would have didn’t exist yet. There wasn’t a baby shower since, at that time in the US, baby showers were reserved for the first-born of the family and I was the second. Gender reveals were not yet the outrageous trend they are today. Despite these historical differences, meaning was still being attached to my existence, in advance of my existence. Surrounding my mom’s pregnancy were social myths – about how low or high her belly was, about her food cravings – that circulated as signs of what I was going to be.

My parents still had “girl” and “boy” names ready to go once they knew “what” I was. My mom’s naming powers were vetoed by my dad after she proposed they name me Ruby, a name that was, at the time at least, unconventional. My dad preferred names that were very of the time: Megan or Eric. Turns out, based on what they were told about me once I did exist outside of the womb, I became Megan, one of the most popular names for girls in the US in the 1980s (my older sister, Heather, had another one of those names).

Once I did exist in the world, the gendered meanings came in full force, authoritatively and subliminally, both different ways in which the dominant meanings of the social fabric ushered me into a particular gendered existence. There was the performative utterance of the doctor – “It’s a girl!” – which began my existence as a girl. While usually taken to be an objective matter-of-fact statement, feminist thinkers have shown that such a statement doesn’t just name a reality but makes the reality itself. I became a girl because I was named one. I wasn’t named one arbitrarily, of course. There was a convention, a tradition, a history in place that made it common sense that at birth, I was clearly, obviously, a girl. No one in that hospital room was going to say otherwise; it would’ve been nonsense. My birth certificate was made, and on it there was a big F, a formal decree of what I was. Beyond these formalities, there was all the social stuff – the flurry of ways people, including my parents, talked to and about me, held me, clothed me, and bought toys for me. Even if they didn’t know it, or even if they didn’t mean to, there was an avalanche of expectations in place about what I was made of. I was to be sugar and spice and everything nice. Still to this day, I have a vivid recollection of a kitschy, wooden sign with that nursery rhyme on it. It wasn’t for me. It was given to my older sister, but the message was clear. Throughout my childhood, the meanings at work in my life became more complex. My parents did not explicitly raise me to be everything nice, or to be seen and not heard. I grew up playing soccer with my mom as my coach. My dad inspired an early fascination with Volkswagen cars, which he encouraged. I played in the dirt and got into trouble with my sister. I wasn’t forced to wear dresses, but they were most often the option available. And yet, still, my childhood was characterized by so many things typical of a white girl in the United States in the 1980s, not to mention that the expectations and values of how I should be were the air that I breathed. As a result, their impact on who I became was inevitable.

When Beauvoir describes the lived experience of becoming a woman, she begins with an account of childhood that underscores the constitutive weight of the social atmosphere on shaping who an individual becomes. What’s “in the air” around us as we come into our existence is central to who we become. For Beauvoir, there is no blueprint for a child’s existence that comes from their genitalia, which is to say that genitalia themselves don’t determine who one is. Rather, a child’s existence is, Beauvoir claims, a result of how their bodily existence is mediated. That sexual difference means anything at all about who we are is a human mediation. A girl, or boy, wouldn’t take their genitalia to have any existential significance without this mediation, without the conferral of meaning. A girl, then, is a girl not strictly because of her genitalia or other physiological differences, but because of how her embodied existence unfolds and is taken up in a given context. It is not her body that dictates who she is. Who she becomes is a matter of her bodily relationality in the world with others. Or, as Beauvoir puts it, the girl’s “vocation [as a woman] is imperiously breathed into her from the first years of her life” (2010, p. 283). This point leads back to the opening sentence of her account of lived experience: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” (1949b, p. 13).

Usually, when I talk with students about Beauvoir’s insistence that the external world is inextricable from the reality of being a woman – which is to say, no one is simply born destined to be a woman – they are quick to jump to the seemingly reliable distinction between nature and nurture. She must be, my students insist, making a point about the significance of nurture. They’re not entirely wrong. Beauvoir is making a case that there is a very deep socialization that those who are girls undergo. In The Second Sex, she offers us pages and pages replete with details about how parents and adults intervene in children’s lives in ways that differentiate girls from boys. Girls are given toys and treated in ways that make them passive, they are told and taught to be pretty and giving, as to focus on doing so is a matter of their worth. Girls are given certain clothes, told to carry themselves a certain way, are taught to do certain tasks while they are barred from others, and are expected to serve others. Ultimately, Beauvoir claims, what adults do is expect that girls accomplish femininity. In fact, she even goes so far as to say adults demand this of girls. This demand is the air girls breathe and it is vital to their becoming women.

To say that the girl’s existence is a just matter of nurture would contradict and oversimplify Beauvoir’s commitments about human existence. For Beauvoir, our development is social; it does depend on the context in which we live out our lives. It does depend on how others perceive and treat us. It is, then, “nurture.” But it’s not just that. There are dimensions of our existence that are inevitable, such as the reality that there are others in the world or that humans, as a species, have basic needs that must be met to stay alive. The term Beauvoir gives this dimension of existence is facticity, and central to this dimension is the body, not as biologically determinative, but in the sense that every subject is bodily, and it is as bodily beings that we have the possibility for existence in the first place. But, before you are quick to think this contradicts the point just made about Beauvoir insisting that genitalia or other reproductive differences do not bear any existential significance, it is important to remember that her point is not that bodies do not matter, but that existence doesn’t boil down to reproductive physiological differences. Embodiment is, for Beauvoir, about so much more than our reproductive organs. Embodiment is about the relation between body and world. It is that how we are touched, who we are touched by, how we move, whether we’re able to, what we desire, are constitutive features of our bodily existence. But that doesn’t mean it’s all “nurture” either. Rather, for her, it is at the entanglement of ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ that we come into existence. Yet these categories aren’t Beauvoir’s terms and using them to understand her work is misleading. The fault of relying on “nurture” is that it doesn’t give any agency to an individual to shape her life, so, although a girl is deeply reared into becoming a woman, it is also, Beauvoir says, a project she undertakes for herself too. Ultimately, Beauvoir doesn’t want to pin down an origin in either side of the nature or nurture debate. She insists instead that we deal with the ambiguity of our existence, that we are never just purely bodies or purely determined from the world imposing itself on us. Rather than locating the origin of the truth of our lives in either nature or nurture, Beauvoir says we must accept that we are always both, that we cannot escape that we have bodily differences and yet we cannot escape the fact that those differences are always lived and experientially constituted in a given context that imbues them with meaning.

The intuition my students have about “nurture,” however, is more accurately understood if we think about the girl as being socialized to become a woman. In Beauvoir’s account, the girl is, without a doubt, deeply socialized to assume her existence as a woman, and as a particular kind of woman, the kind that conforms to patriarchal ideology. Indeed, for Beauvoir, there’s no doubt that in childhood there is significant external demand on a girl...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Schlagworte | biological sex • books about gender • detransition • Feminism • gay • gender affirmation • Gender debate books • gender discussions • Gender identity • Gender Ideology • Ideology • Julie Bindel • kathleen stock • Lesbian • non-binary • politics of trans existence • Sexuality • Simone de Beauvoir • theory of feminism • The Transgender Issue • transgender rights • trans rights activism • what are real women • What are the main points of gender performativity? • what does Simone de Beauvoir say about trans inclusion • what do feminists think about transgender • what is gender transition • womens safety |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6200-1 / 1509562001 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6200-8 / 9781509562008 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 181 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich