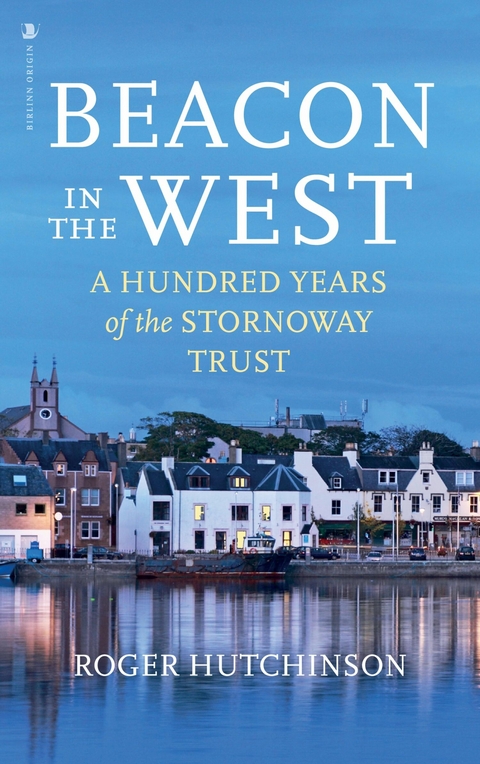

Beacon in the West (eBook)

224 Seiten

Origin (Verlag)

978-1-78885-593-8 (ISBN)

Roger Hutchinson is an award-winning author and journalist. After working as an editor in London, in 1977 he joined the West Highland Free Press in Skye. Since then he has published thirteen books, including Polly: the True Story Behind Whisky Galore. He is still a columnist for the WHFP, and has written for BBC Radio, The Scotsman, The Guardian, The Herald and The Literary Review. His book The Soap Man (Birlinn 2003) was shortlisted for the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year (2004) and the bestselling Calum's Road (2007) was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature's Ondaatje Prize.

Roger Hutchison is an award-winning author and journalist. In 1977 he joined the West Highland Free Press. His book The Soap Man: Lewis, Harris and Lord Leverhulme was shortlisted for the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year in 2004 and Calum's Road was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literatures Ondaatje Prize in 2007.

3

Prohibition and Population

The first task of the Stornoway Trust was to stabilise Lewis. As the voyage of the Metagama indicated, the most serious effect of the Leverhulme withdrawal was to create an almost existential uncertainty in that previously confident and assertive island.

Lewis in the 1920s was not a happy place. The Glaswegian physician Halliday Sutherland visited the island for the first time in 1923, shortly after Leverhulme’s departure. ‘When I reached Stornoway,’ Sutherland recalled ten years later in his travelogue Hebridean Journey, ‘I found a half-built factory on which work had been abandoned, a derelict small-gauge railway, and thousands of pounds’ worth of machinery rusting on the shore.’

Halliday Sutherland was a recent convert to Roman Catholicism and he was equally distressed to discover that the windows of Stornoway’s small and makeshift Catholic chapel had been smashed. ‘During the previous year,’ he recounted from second-hand information, ‘a handful of Catholics had attempted to hold a service in the church and a crowd had pelted the building with stones.’

On top of that, Halliday Sutherland found it difficult to drown his distress. In November 1920, following the provisions of the Temperance (Scotland) Act 1913, the island of Lewis had voted for the prohibition of retail alcohol. In May of the following year, 1921, under the Temperance Act, four retail licences in the burgh of Stornoway lapsed and were not renewed. That local bylaw was agreed upon two years after Andrew Volstead’s more famous National Prohibition Act had been enforced in all of the United States. It was not an unusual measure, at the time or later, in the Protestant Celtic fringes of the United Kingdom.

Across the whole of Scotland prohibition was limited. When people were free to debate and vote on the 1913 Act, following the Armistice of 1918, alcohol bans were introduced in Kilsyth, Kirkintilloch, Wick and Lerwick. At one point or another, sixteen council wards across Scotland went dry. But only twenty-three of Scotland’s 253 districts voted for ‘no licence’ prohibition and a further thirty-five regions saw some limitations placed on alcohol sales.

Unlike the Volstead Act, prohibition in Lewis was necessarily an isolated affair. Not only did it take place within a country – within, indeed, a county – where the purchase and consumption of retailed alcohol was in other districts still legal and relatively unlimited, but its strictures in practice applied almost exclusively to Stornoway, as there were no public bars elsewhere in the island of Lewis.

It was a half-hearted and short-lived prohibition. It was certainly promoted by the dominant Free Churches, and widely supported by Lewis women of property who, having been granted limited national suffrage in 1918, found themselves suddenly enfranchised to vote in the local prohibition referendum two years later.

Bizarrely to outside eyes, it did not apply to Harris, which was still in the permissive embrace of Inverness rather than Ross & Cromarty County Council, which had not held a prohibition referendum and whose single hotel bar therefore remained unaffected.

The measure emphatically did not, as Sutherland would discover, create a teetotal island of Lewis. In 1922, the first full year after the retail alcohol licence ban came into place, it was revealed that one Stornoway wholesaler alone imported ales and spirits to the value of £24,887, which was almost half the amount invested by all the town’s wholesalers in 1920, the last full year before prohibition. Provost Kenneth Mackenzie, while paying lip service to the result of the local referendum, publicly regretted, ‘The conditions under which liquor is now supplied and consumed are – to say the least of it – degrading and demoralising.’

‘It was possible to buy whisky from a licensed grocer,’ observed Halliday Sutherland, ‘provided one bought half a gallon at a time. Men would club together to buy this amount and carry it down to the foreshore, where they drank it. Consequently, drunkenness was not unknown, and for the twelve months following the veto of local option, the amount of alcohol imported into the island had increased. In the more remote places private stills were working.’

Only smaller units of strong drink were banned. It remained legal, as Sutherland suggested, to buy wholesale quantities, such as cases of whisky and casks of beer. That loophole was intended to alleviate the suffering of large hotels, which were permitted to serve drinks with meals to guests, and to lubricate the social wheels of the bigger private houses. In practice it also gave a new lease of life to the rural township bothan in Lewis, to which Kenneth Mackenzie, whose roots were in rural Lochs, was referring as ‘degrading and demoralising’.

In many communities a crude but largely weatherproof building was set aside as a drinking den. The men would contribute to a kitty, wholesale cases and casks would be – perfectly legally – imported, and the bothan would thereafter serve as a private club. This arrangement proved so congenial to the communitarian crofting townships (wholesale alcohol was, after all, cheaper by far than anything bought at a bar or even from a shop) that in some cases the shebeen long survived the repeal of prohibition and for decades staved off the introduction of licensed commercial premises.

In the rural district of Ness a working bothan survived as a viable alternative to a public bar for more than half a century after 1921, and it was finally put out of business not by a public house but by another community venture: a newly built social club run by and for the benefit of the local football team.

In some northern fishing ports, a full or partial alcohol prohibition held sway for decades. In the Caithness town of Wick, no public houses or licensed grocers were permitted to sell alcohol to the public between May 1922 and May 1947. In Lewis the ban on alcohol licences lasted for five years. It was repealed by another public vote in 1926.

In October 1923 the district Nursing Committee at Ness reformed itself into an Emergency Relief Committee. The headmaster of Lionel School grew so concerned by the malnourished condition of his pupils that he issued a public appeal for funds to provide them with a midday meal. Sir William Mitchell Cotts MP appealed unsuccessfully to the Scottish Secretary Lord Novar to resume the Ness–Tolsta road works which had been abandoned by Leverhulme.

Almost a full year of preternaturally wet weather resulted in the failure of the potato crop throughout the Hebrides and the west mainland. In Lewis itself only a handful of days in May, June, July and August had been completely dry, just one day in September had seen no rain, and in the whole of October and November there was ‘not recorded one single instance of twenty-four consecutive hours dry’. Peats and corn had been too wet to harvest properly. Cut hay lay blackening on the ground. Severe equinoctial storms blew down the few stooks of fodder and wiped out most surviving crops in west-coast districts such as Callanish.

The fishing industry remained in deep depression. Clothing and food parcels were distributed throughout the islands by charitable organisations and Highland societies. People said that matters had never been worse since the Hungry Forties of eighty years before. The fishing township of Cromore in Lochs was reported late in 1923 to be in a condition of ‘destitution . . . there is no place, even in Lewis, where things could be worse’. A meeting at Back Free Church warned of ‘starvation in many homes. The people have nothing to fall back upon owing to the failure of the fishing industry, the complete failure of the potato crop, and the lack of work of any kind.’

At Westminster in the new year of 1924 the freshly elected radical Liberal MP for the Western Isles, Alexander MacKenzie Livingstone, pleaded urgently but in vain for a Commission to be appointed to investigate ‘the exceptional economic conditions prevailing in the Western Isles’.

The first Labour Scottish Secretary, William Adamson, who took office following the December 1923 General Election, acknowledged the ‘exceptional distress in Lewis this winter’ and announced that the government would be supplying the Highlands and Islands ‘at a reduced cost [with] seed oats and seed potatoes for use this spring’.

Across the other Hebrides, land raiding resumed. In Lewis a generation continued to emigrate. On Saturday 26 April 1924, the Canadian Pacific Railways liner SS Marloch put into Stornoway and carried away with her to the New World 290 young Lewis men and women. Most of them travelled on the government of Ontario’s Assisted Passages Scheme. The men were bonded to become farm labourers until they had repaid the debts of their passage; the women to be domestic servants.

Not all of the young men were gone forever. To some the Metagama and the Marloch offered an opportunity to adventure out in the world rather than settle on a Canadian prairie farm. Donald Campbell, the great-uncle of the memoirist, journalist and future member of the Stornoway Trust Calum ‘Safety’ Smith, left Lewis in 1926 and returned to Stornoway on the mail steamer in 1932. In his six years away, he travelled thousands of miles between Baltimore, New Orleans, Seattle, Vancouver, Winnipeg and Montreal. Following his return, he hardly left Lewis. Donald...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 8pp colour plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| Schlagworte | Island History • Local History Organisations • Scotland • Scottish History • Scottish Islands • Stornoway • Stornoway Trust |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-593-0 / 1788855930 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-593-8 / 9781788855938 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich