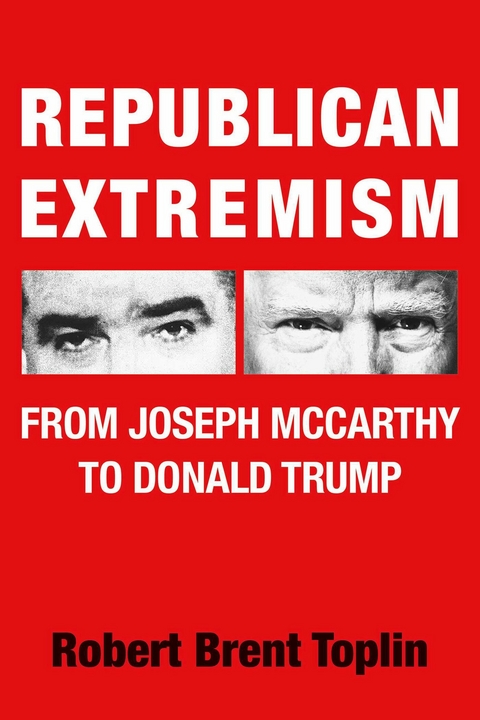

REPUBLICAN EXTREMISM (eBook)

256 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-4953-7 (ISBN)

Robert Brent Toplin, a university-based professor, has published a dozen books and more than 150 articles about history, politics, and film. He has commented on history in several nationally broadcast television and radio programs and has received numerous awards and fellowships for scholarship and teaching.

Republican extremism is running amok. How did the GOP get in this mess? Robert Brent Toplin shows the radical shift occurred long before Donald Trump entered the White House. An early sign of trouble occurred in the 1950s when Joseph McCarthy engaged in reckless demagoguery. In later decades militants purged moderates, rejected compromise, and disparaged political opponents. Now extremism poses a crisis for the United States and the world. This gripping narrative, loaded with fascinating details, shows how the Republican Party lurched to the right and polarized the nation through its positions on elections, the presidency, the economy, the Supreme Court, race relations, guns, immigration, Covid, crime, the mass media, climate change, international relations, and warfare. Republican Extremism is essential reading for anyone seeking insights on the origins of America's fractured politics. "e;What a wide-ranging book, a fast-paced read, full of shrewd insight and provocative arguments."e; BRUCE SCHULMAN, author of The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Politics, and Society"e;Robert Toplin's perceptive and wide-ranging book Republican Extremism reveals how Donald Trump is not an exception but part of a long legacy of Republican demagogues stretching back to Senator Joe McCarthy."e; STEVEN J. ROSS, author of the Pulitzer Prize Finalist, Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America "e;Robert Toplin's insightful book brings the weight of history to bear on the strain of radicalism that now infects the Republican Party."e; JOHN BODNAR, author of Divided by Terror: American Patriotism Since 9/11Robert Brent Toplin, a university professor, has published a dozen books and more than 150 articles about history, politics, and film. He has commented on history in nationally broadcast television and radio programs and has received numerous awards and fellowships for scholarship and teaching.

TWO

Promise and Peril in the Fifties

This analysis points out that the Republican Party under President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s leadership provided a model of center-right politics. Eisenhower encouraged the GOP to become “modern,” a term that suggested moderation.

Some important political achievements in the Fifties were bipartisan. The Eisenhower Highway Act of 1956 was a notable example. That legislation stimulated enormous economic growth throughout the nation.

In the early Fifties a problem appeared that polarized American politics. Joseph McCarthy, a reckless demagogue, achieved considerable political clout. In 1954 changing domestic and international conditions as well as McCarthy’s excesses led to his demise. There are lessons in this history. In related ways Donald Trump’s also weaponized the politics of fear.

Good Old Days: Consensus in the 1950s

Tired of partisan clashes? Weary of seeing pundits of the Left and Right scream at each other on television? Then discover greater peace of mind by looking back to a time when Republicans and Democrats got along much better. At least that is the characterization of U.S. politics in the 1950s presented by Arthur Larson, who served as one of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s top speech writers. In A Republican Looks at His Party, an influential book of 1956, Larson describes less angry, indeed, friendlier times. He claims leaders in Washington achieved a form of “consensus”– basic agreement on the major political issues – in the Fifties. Legislators discarded their ideological baggage, says Larson. He identifies a Republican Party that is quite different from the radically conservative organization of today. In fact, Arthur Larson gives the GOP major credit for advancing pragmatic approaches to politics, and he praises the Republican president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, especially, for making that achievement possible.

According to Larson, lots of Americans realized in the Fifties that the old politics of ideological clashes between the Right and Left no longer served the nation well. Before the Great Depression leaders had pushed laissez faire to extremes, Larson notes. That approach was unfortunate, because it produced inequality and left the financial system vulnerable to a breakdown. Then liberals reacted to the economic problems by elevating the position of ordinary Americans through a variety of New Deal programs. But Larson concludes that liberals often made government excessively intrusive in business affairs.

President Eisenhower took the best of both traditions and avoided the extremes, Larson argues. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s policies gave both sides lots to cheer about. Liberals appreciated Eisenhower’s support for an expansion of Social Security benefits. They also liked construction of the interstate highway system, a vast public works program that stimulated the economy and created thousands of jobs. Conservatives were happy to see that Eisenhower backed pro-business measures. The President recognized that the American people’s suspicion of big business had become excessive during the Great Depression. It was time to liberate businessmen from burdensome restrictions established by Washington’s legislators and bureaucrats. Private enterprises needed to operate more freely to make the economy dynamic.

Arthur Larson acknowledged the old ideological divisions had not passed away completely Some Americans were still inclined to support radical positions of the Left and Right. But those people constituted “small minorities,” he assured readers. Extremists were not a serious threat to the political order because, “they are out of tune with the feelings of the overwhelming majority of Americans.” Larson expressed confidence that a new “American Consensus” was here to stay.

We understand now that Larson was much too sanguine about prospects for achieving long-lasting agreement on political fundamentals. When he published A Republican Looks at His Party in the mid-Fifties, some leaders on the right were already launching a partisan conservative movement (as in the case of William F. Buckley, who began publishing the National Review in 1955). Liberals, too, expressed discomfort with the idea of “consensus.” In the Sixties many of them claimed the nation needed to battle poverty, inequality, racial discrimination, and other problems more aggressively.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the American Consensus that Arthur Larson described so glowingly no longer seemed relevant. U.S. politics became polarized. Disagreements over the Vietnam War, civil rights, black and white protests, crime and violence, women’s liberation, abortion, and other issues made “conflict” not “consensus” appear more characteristic of America’s political culture.

Later, shifts within the parties widened the ideological divide. Conservative Democrats, including many southerners resistant to racial integration, moved into the GOP’s camp. Some liberal and moderate Republicans felt uncomfortable within the rightist-oriented GOP. They shifted to the Democrats or identified as independents.

Arthur Larson was overly optimistic when he concluded in the mid-1950s that Washington had achieved an impressive degree of harmony and that the Republican Party could lead the nation forward. He did not see that the cooperative spirit could break down quickly, nor did he appreciate how much his own party would soon contribute to the nation’s fragmentation.

From today’s perspective, Arthur Larson’s interpretation appears naïve, but his assessment is important, nonetheless. A Republican Looks at His Party reminds us that for a brief time in the 1950s many Republicans and Democrats favored pragmatism over ideology. Unfortunately, the spirit of political cooperation and negotiation was not realizable in the long run. Clashes over substantive issues soon disrupted the consensus. Larson’s book showed that the dream of an effective centrist order inspired genuine hope in the Fifties about Washington’s potential to achieve significant progress.

Productive Bipartisanship: The Eisenhower Highway Act of 1956

In the 1950s President Dwight Eisenhower proposed the largest single infrastructure program in U.S. history – construction of a vast interstate highway system throughout the United States. Congress debated the proposal at length. At first, many lawmakers said the plan was expensive, and they could not agree on how to pay for it. Eisenhower maintained the investment in infrastructure would ignite an economic boom. He was right. That gigantic project fueled prosperity in the Fifties, Sixties and beyond.

In the 2020s, President Biden promoted another huge economic lift through his infrastructure plan. It stimulated new development of roads, bridges, ports, railroads, airlines, broadband, and electric power and it sped America’s shift toward clean energy. Many Republicans objected to Biden’s proposal. They complained that it cost too much and involved excessive government interference in business affairs. Those critics failed to recognize the value of infrastructure investment stimulated by smart government planning. Republicans could have better appreciated the wisdom of Biden’s proposal if they examined the history of the interstate highway construction program of the Fifties. That bi-partisan legislation jump-started vigorous economic growth.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower is often identified as the “father” of America’s interstate system because he promoted the idea and construction began under his watch. But the roadway system really had two key “parents,” not one.

Back in the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for a related highway program as part of his New Deal commitments to public works. Roosevelt was an enthusiastic champion of superhighways.20 He believed a web of modern four-lane roads could spark economic development and provide construction jobs for unemployed Americans during the Great Depression. Unfortunately, he pitched this argument in the late 1930s, a difficult time to launch expensive new projects. An economic recession in 1937 and early 1938 diminished support for his New Deal. Furthermore, Republicans won many congressional races in the 1938 elections. Republicans wanted to cut federal spending. In 1939 and beyond, worries about German, Italian, and Japanese aggression led Roosevelt to concentrate on a buildup of America’s military. The highway project languished.

It came back to life when Dwight D. Eisenhower was president. Eisenhower had become interested in highway construction in 1919, shortly after World War I ended. At the time he was a U.S. Army officer and directed a large caravan of military vehicles from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. Traveling across the country took two months. The trip was difficult because of the nation’s primitive road conditions. Eisenhower recognized motor transport needed a much better road system. Later, in World War II, Eisenhower served as the Allies’ supreme commander in Europe. When Eisenhower entered Germany, he saw that country’s modern, high-speed autobahn. These two experiences influenced President Eisenhower’s decision in the 1950s to promote a new highway program. 21

Both Republicans and Democrats were concerned in the Fifties about recessions. They thought an interstate system could build a strong foundation for long-term economic growth. But they were sharply divided...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-4953-7 / 9798350949537 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 906 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich