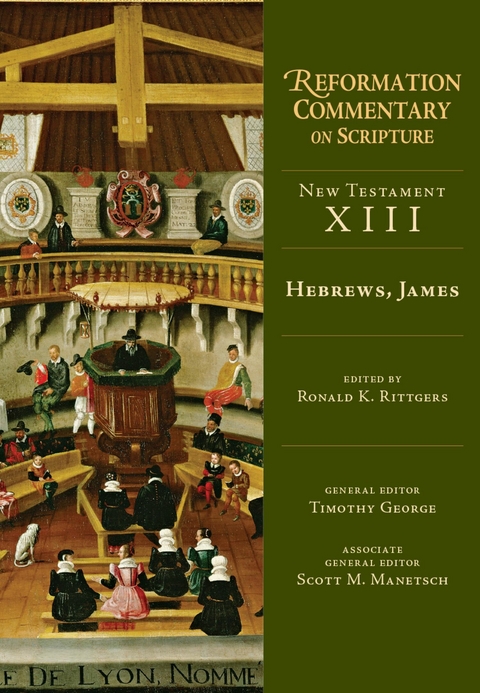

Hebrews, James (eBook)

300 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-0-8308-8942-6 (ISBN)

Ronald K. Rittgers (PhD, Harvard University) holds the Erich Markel Chair in German Reformation Studies at Valparaiso University, where he also serves as professor of history and theology. He is the author of The Reformation of Suffering: Pastoral Theology and Lay Piety in Late Medieval and Early Modern Germany and The Reformation of the Keys: Confession, Conscience, and Authority in Sixteenth-Century Germany. He has also served as the president of the American Society of Church History.

Ronald K. Rittgers (PhD, Harvard University) holds the Erich Markel Chair in German Reformation Studies at Valparaiso University, where he also serves as professor of history and theology. He is the author of The Reformation of Suffering: Pastoral Theology and Lay Piety in Late Medieval and Early Modern Germany and The Reformation of the Keys: Confession, Conscience, and Authority in Sixteenth-Century Germany. He has also served as the president of the American Society of Church History.

Introduction to Hebrews and James

A Controversial Epistle: Hebrews in Reformation Commentary

The epistle to the Hebrews occupies an important place in the history of Reformation biblical interpretation.1 Some scholars have argued that Luther’s lectures on Hebrews (1517/1518) contributed directly to the emergence of his mature Reformation theology. Earlier in his career Luther had treated faith as a kind of humility that the Christian was both able and obliged to produce in response to the accusing Word in order to merit grace; in his Lectures on Hebrews the Wittenberg professor treats faith as trust in the promises of the Word.2 Luther instructs his students in these lectures to despair of their self-made penitence and purification from sin, because their forgiveness does not depend on these: it is Christ’s purification for sins (Heb 1:3) that produces their penitence, and the same purification has already forgiven them before they begin to repent.3 For Luther, faith is now a “clinging to the Word,” that is, a deep trust that causes the heart to soften toward God and ultimately unites it with Christ, causing the believer to become like the Savior. As Luther explains,

For this clinging is the very faith in the Word. Indeed, it is that tie of betrothal about which Hosea 2:20 says: “I will betroth you to Me in faithfulness,” according to the well-known statement in 1 Corinthians 6:17: “He who clings to God is one spirit with him.” . . . It follows as a corollary that faith in Christ is every virtue and that unbelief is every vice. . . . For through faith a man becomes like the Word of God, but the Word of God is the Son of God.4

Luther makes the gift of faith the defining mark of the Christian:5 “For if you ask a Christian what the work is by which he becomes worthy of the name ‘Christian,’ he will be able to give absolutely no other answer than that it is the hearing of the Word of God, that is, faith. Therefore the ears alone are the organs of a Christian man, for he is justified and declared to be a Christian, not because of the works of any member but because of faith.”6 As Luther reached the end of his lectures on Hebrews (summer 1518), he could declare that Abraham, the man of faith (Heb 11:8), “gave a supreme example of an evangelical life, because he left everything and followed the Lord. Preferring the Word of God to all else and loving it above all else, he was a stranger of his own accord and was subjected every hour to dangers of life and death.”7 Abraham clung to the Word by faith and willingly endured the suffering that both proved this faith and followed from it. He was the ideal Christian for Luther as the monk-professor became caught up in the indulgence controversy (fall 1517 to fall 1518).8

Not all scholars agree with this argument about the centrality of the Lectures on Hebrews in the development of Luther’s Reformation theology; many would say that Luther’s evangelical understanding of faith may be found in his earlier works as well.9 Nevertheless, for some time now, Reformation scholars have paid close attention to the way Luther and a whole host of reformers treated Hebrews in their sermons, lectures, and commentaries. Kenneth Hagen, who has done the most work on this topic, has concluded that “among the epistles, the one to the Hebrews was the most controversial” in the eyes of the reformers.10

The pages that follow provide warrant for Hagen’s claim. It will be helpful to provide the reader with a general orientation to the central theological and exegetical issues that appear in the reformers’ comments on Hebrews. Authorship is foremost among them. The reformers were well aware of debates since the early church about the authorship and apostolicity of the epistle to the Hebrews. They express different opinions on these important matters, some claiming Pauline authorship, others denying it and either leaving the question of authorship open or suggesting an alternative, such as Apollos. The early arguments of Cajetan and Erasmus against Pauline authorship, which Luther and Calvin shared, appears to have set the scene for ongoing debate among reformers. Still, many accepted the traditional position: Zwingli argues for Pauline authorship, as do a number of Reformed theologians. Unlike debates about the authorship of James (see below), disagreements about the authorship of Hebrews did not lead to more thoroughgoing questioning of its canonical status—although a few Lutherans attempted to relegate Hebrews to a kind of apocryphal status within the New Testament.11

Christology is a major theme in Hebrews. The reformers comment at length on the relevant passages as they seek to explain how the Son is related to the Father and Holy Spirit, as well as to the created order, including angels. The reformers affirm Nicene and Chalcedonian orthodoxy; however, they disagree vigorously concerning the nature of Christ’s presence in the holy bread and wine. Christ’s session at the right hand of the Father (1:3, 13) especially provoked these christological debates. Following Luther, Lutheran commentators insist on a figurative session of Christ along with the ability of his human nature to participate in the ubiquity of his divine nature, thus making it possible for Christ to be present in, with, and under the auspices of bread and wine. Reformed theologians argue against the Lutheran view of Christ’s session, especially what it assumed about the relationship between Christ’s humanity and divinity, and thus insist on Christ’s spiritual presence in the Lord’s Supper, depicting Lutherans as perpetuating the traditional “superstitious” view of the sacrament.12

The reformers were especially impressed with another aspect of Christology in Hebrews, especially in their comments on Hebrews 2:5-18: the veiled nature of Christ’s glory. The reformers saw in this hiddenness a summons to faith in the hidden God. The reformers also reflect on the nature of Christ’s suffering, especially the suffering of his soul, but they consistently move from considerations of Christology to pastoral concerns, finding in Christ’s incarnation and humiliation consolation for the suffering and persecuted (Protestant) Christian. The reformers make a great deal of the “fellowship of suffering” that they see between Christ and Christians in Hebrews and offer it as a source of solace to their contemporaries.

The reformers also tackle the thorny christological issue of how Christ, the God-man, may be said to have learned obedience through what he suffered (Heb 5:8). Most emphasize that Christ learned by experience what he already knew in theory about obedience, especially in the midst of suffering, and that by suffering to the point of death he showed Christians what true obedience to God entails. But pastoral concerns again predominate as the reformers see in Christ’s suffering a source of consolation for the afflicted Christian. Edward Dering says that this passage contains a “salve against the wounds of sorrow,”13 for Christians can know that Christ is present with them in their afflictions, and that their prayers for help and comfort will be heard because of Christ’s obedience in their stead.

That Hebrews ostensibly teaches that salvation can be lost through serious postbaptismal sin (2:1-4; 6:4-12; 10:19-39) sits rather awkwardly with most versions of justification by faith. Theologically speaking, this was the most challenging aspect of Hebrews for the reformers. The magisterial Protestants were trying to deliver their contemporaries from a theology of salvation that, in their eyes, provided no certainty of forgiveness because it was based on the dubious foundation of human good works rather than on the sure foundation of God’s word and character. In the eyes of the reformers, this teaching had caused untold anxiety in human consciences, as Christians wondered whether they had ever done enough to appease the divine Judge. Justification by faith rested on the conviction that salvation was God’s good work from beginning to end, and that this gift could in no way be earned but only received by faith, itself a gift. Salvation was certain because it rested on God’s character and action, not in any way on human effort. Thus, an uncertain salvation—a salvation that could be lost through human failure—was diametrically opposed to the theological and pastoral designs of the reformers. But they also wished to be true to Scripture, including its difficult passages, for they insisted that unlike “popish” theology, theirs was based on the Word of God. For the most part, the reformers interpret the “harsh” or “rigorist” passages on loss of salvation in Hebrews as being either hyperbolic or as applying to the reprobate and indolent rather than to the elect, although some do allow for the possibility of a complete fall from grace among believers, apparently owing to the strength of indwelling sin, the world, and the devil. In other words, on the whole, the reformers see in such passages a dire warning to keep believers in the narrow way of salvation, or they see these passages as applying to those in whom the seed of salvation had never taken firm root.

The...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.11.2017 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Reformation Commentary on Scripture |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum |

| Schlagworte | 16th century • Bible • biblical commentary • biblical exegesi • Commentary • Early modern • Epistle • Hebrews • James • Protestant Reformation • RCS • Reformation • Reformation commentary on scripture • Reformation-era • Reformation Studies • Reformers • Scripture • sixteenth century |

| ISBN-10 | 0-8308-8942-6 / 0830889426 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-8308-8942-6 / 9780830889426 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich