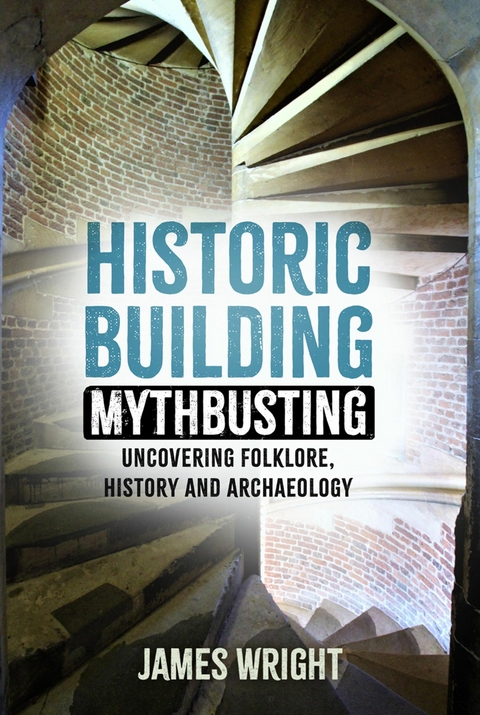

Historic Building Mythbusting (eBook)

228 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-448-2 (ISBN)

JAMES WRIGHT is a buildings archaeologist at Triskele Heritage who specialises in mediaeval and early modern architecture. He holds a PhD in Archaeology from the University of Nottingham, and is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and an affiliate of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation. He has led buildings archaeology surveys at major properties including the Tower of London, St Mary's Warwick, Palace of Westminster, Tattershall Castle, Southwark Cathedral and Knole. He won Best Archaeological Project at the British Archaeology Awards for his work at the latter. He has also surveyed dozens of domestic vernacular buildings from Wiltshire to Lancashire and from Norfolk to Powys.

INTRODUCTION

Historic buildings matter. We go to meet our good friends in the creaky old pub. Days out often centre around a trip to a country house. Holidays are taken in towns with a wealth of eye-catching edifices. Weddings are held at rambling, ancient castles – perfect backdrops for the all-important photographs. Some people dream of moving to the idyllic cottage in the country. The good times in our lives are closely associated with beautiful ancient buildings. Even the trying moments of life can take place in historic structures – examinations in school or university halls, planning applications made in town halls, or funerals in mediaeval churches. Society places a very great importance on buildings steeped in history and architectural design is integral to how communities perceive themselves and are, in turn, perceived.

Part of the attraction of historic buildings are the human stories connected to them. Some tales are accurate (to the best of our knowledge). We can visit Newark and see the castle where King John died in 1216, the spot where Henry VIII witnessed the sinking of the Mary Rose near Southsea Castle in 1545, and the church of Holy Trinity at Stratford-upon-Avon where William Shakespeare was baptised in 1564.1 Some stories are more debatable. It is no longer certain that Edward II died at Berkeley Castle and Richard III may not have slept at the White Boar in Leicester the night before the battle of Bosworth Field.2 Other events probably did not happen at all. If Dick Turpin had a pint in every pub that that he is rumoured to have supped in, he would have pitched up at the gates of York in an advanced state of shambolic inebriation*.

This book is fundamentally about the stories that are told about the fabric of buildings. The ways in which buildings were constructed. The ways in which they were used. The ways in which people have altered their appearance. Tales grow up around buildings that are faithfully assumed to be true and are commonly repeated. Repetition by figures of authority – including older relatives, builders, teachers, journalists, media presenters, local historians, curators, and academics – help to make these stories believable. However, many are mere hyperbole, tall tales with foundations built on sand.

In this book we will look at some of those yarns in detail. I am certain that some of them will be familiar to you. Indeed, you may have believed and repeated one or more of them. Tales of secret passages linking historic buildings can be found in all corners of the country. The belief that spiral staircases in castles turn clockwise to advantage the sword swing of right-handed defenders is repeated daily. The patrons of old pubs are frequently told that the very timbers of the buildings in which they drink were reclaimed from shipwrecks. If you have believed any of these tales, there is no judgement here. Historic buildings are complex structures and understanding them can take a lifetime of study. Many of these stories are eminently plausible on first encounter – especially so if repeated by someone who sounds like they know what they are talking about.

Some of the book is concerned with the archaeology of buildings (although not exclusively so), for that is my profession – I am a buildings archaeologist. Unlike many of my archaeologist colleagues who are crouched in muddy holes, plagued by the wind and the rain and the cold, I study the archaeology of buildings. There are certain advantages. Most places that I work at have roofs, some have heating, and, on the really good days, there might even be a bar (see Chapters 8 and 9). But why, you ask, would an archaeologist be interested in something that is standing – in plain sight – above ground? Well, most historic buildings have never received any meaningful research and, even when histories have been established, the structural fabric is often left unconsidered in detail. Architectural historians are constrained by the availability of archives that reveal the documented story of a structure and the origin of many buildings can be shrouded by a lack of written records.For example, the earliest reference to a house that I surveyed in Sible Hedingham, Essex, was 1673, yet the archaeology of the building indicated that it was constructed during the late fifteenth century. Without buildings archaeology, a whole two centuries would have been missing from the record.3

The role of the buildings archaeologist relies upon a multi-disciplinary approach – colloquially referred to by my old university tutor, Philip Dixon, as ‘using all of the available tools in the toolkit’. First and foremost, buildings archaeology relies on the trained knowledge and experience of practitioners – our eyes and brains are the most important pieces of equipment on site (followed by camera, clipboard, piece of plain paper, pencil, rubber and measuring tape). We make observations of the form, function, materials, history, phasing, setting, context, and significance of historic buildings. This work is done by deploying a combination of techniques that may include visual observation, note-taking, measured drawings, photography, laser scanning, photogrammetry, archival research, and dendrochronology (tree-ring dating). Much of our time on site is spent trying to work out the physical relationships between various phases of building. We then write up the results of the survey as grey literature site reports, journal articles or books. Additionally, our work can be presented through apps, websites, videos, interpretation panels, media stories, leaflets, guidebooks, lectures, podcasts, or television programmes. Much of what you will read about in this book is gathered from the last two decades (and more) during which I have been ferreting around in buildings looking for historical, archaeological, and architectural clues.

Despite the rather forensic nature of buildings archaeology, it may surprise some that I am equally happy in the world of folklore. That requires an altogether different set of approaches, but the subject can be incredibly rewarding when trying to understand how and why people think the way that they do about buildings (and much else). It is acknowledged that many of the stories interrogated within this book do not have foundations in the lived reality of the supposed historical period or setting. Without giving too much away, the story covered in Chapter 5 – that the walls of some churches have grooves created by bowmen sharpening their arrows – is not rooted in mediaeval archery practice. The tale grew up during the post-mediaeval period, but it still has value because it tells us some important truths about the concerns of the society that created it.

It would be easy, and unfortunate, to write a book in which popular myths about historic buildings are debunked in a high-handed, condescending, or patronising tone. I genuinely hope that is not what I have done here. Instead, I have tried to pen something that adopts a questioning curiosity and attempts to understand if there could possibly be any truth behind the tales. Sometimes there is foundation to the stories (see Chapter 8, on ship timbers). However, if it is found that there is no basis in fact then I am still deeply interested in the way in which the stories formed and what they can tell us about the people who have told and continue to tell them. Folklore is partly the study of traditional beliefs that permit insight into the way that people think. The ability to understand folk belief, even mistaken belief, provides tremendous insight because, throughout history, written chronicles have tended to emphasise the lives of elites and other voices are often absent Folklore offers one way to understand thought patterns, emotions and psychology that is lacking from some other fields. Archaeology can sometimes do this, too. That is not to denigrate the work of historians. The written word plays a strong part in this book and many of the conclusions are based on historical sources. Most often, though, our springing point will be a piece of folklore or ‘urban myth’. In Chapter 7, folklore really comes into its own as it is partly through the context of traditional beliefs that we can attempt to understand the meaning of burn marks in historic buildings.

Most of these tales are connected to mediaeval buildings but I freely admit to liberally straying into the early modern period (sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) and, on occasion, into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Each chapter will take on a particular subject in detail. The tale will be articulated initially using real-world examples, the evidence for and against will be examined, and an assessment will be made as to whether it is a complete myth, a plausible story, or if it is entirely factual. There will also be an attempt to explain the context of the story. Some of the conclusions surprised me. When I set out on this project, I never anticipated that, in Chapter 2, I would be able to potentially identify the earliest citation of the spiral staircase myth and to be able to understand its genesis through the biography of its probable inventor.

When attempting to debunk any myth there is always a danger that the individual doing the myth-busting may get certain points incorrect. To try and alleviate this concern, at all points in the book, I will show my ‘working out’. The text is strewn with superscript numbers that link to endnote references (gathered in a list towards the end of the book). The endnotes will show the source of my information. This might be a Harvard-style reference to the author, year of publication and page number of a book that can then be...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 25 colour illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Archäologie |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Schlagworte | Architecture • castles • chapels • Churches • historical myths • historic churches • historic houses • Historiography • history myths • Manors • mansions • mediaeval building • medieval building • middle ages buildings |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-448-7 / 1803994487 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-448-2 / 9781803994482 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 17,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich