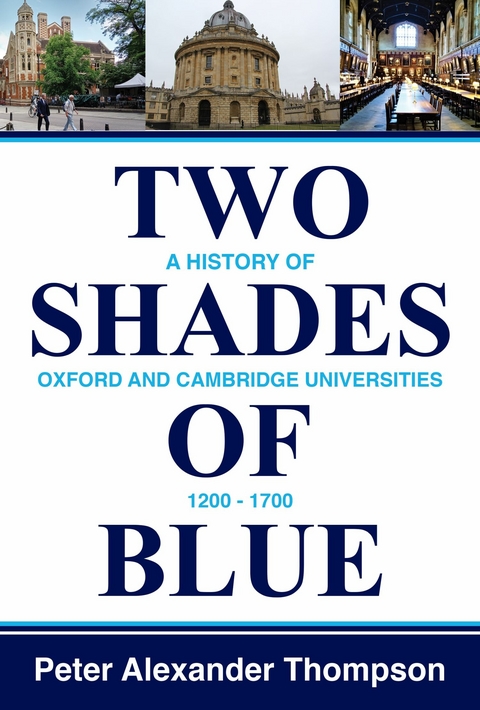

Two Shades of Blue (eBook)

718 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-5740-2 (ISBN)

Award-winning author Peter Alexander Thompson, a London-based former Fleet Street editor, has written twenty-one books on war, royalty and big business. His titles include Maxwell: A Portrait of Power, the first biography to expose the criminality of the media magnate Robert Maxwell, and Cudlipp's Circus, a memoir which reveals how the author collaborated with the BBC's Panorama team to make 'The Max Factor', the TV documentary that precipitated Maxwell's dramatic fall. Thompson won the Blake Dawson Prize for Business Literature, with co-author Robert Macklin, for The Big Fella: The Rise and Rise of BHP Billiton. Other works are The Private Lives of Mayfair, an historic account of Mayfair personalities over 350 years; Pacific Fury, a best-selling one-volume history of the Pacific War; The Battle for Singapore 1942 and The Quest for Freedom, a biography of Alexander Kerensky and the Russian Revolution. His new book, Two Shades of Blue, is the first of two volumes that will cover the histories of Oxford and Cambridge Universities from their founding in the Thirteenth Century up to the reforms and advances of the modern era.

At a time when the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge are again under sustained attack from activists and politicians, Two Shades of Blue takes the reader in two volumes from their founding in the early Thirteenth Century up to the reforms and advances of the modern era. The title, Two Shades of Blue, refers to the sporting colours of dark blue for Oxford and light blue for Cambridge. The first volume encompasses the 500 years between 1200 and 1700, starting with the pioneering Oxonians Robert Grosseteste, Adam Marsh and Roger Bacon, and examines the claims of Merton, University and Balliol to be the oldest surviving college. It covers the founding of Cambridge University following the great dispersal of 1209 and the development of aularian houses into residential colleges. It explores the religious turmoil created by John Wycliffe, 'the morning star of the Reformation', who inspired Lollardy, the pre-Protestant movement that would challenge papal authority and campaign for the Holy Bible to be printed in English. It covers Henry VIII's break with Rome which created a dangerous schism in both Universities and cost the Cambridge Chancellor John Fisher and his friend, Sir John More, their lives. The 'New Learning' of the Renaissance reached Oxford in the late 1490s through John Colet, William Grocyn and Thomas Linacre but it was Erasmus who lit the lamp of humanism during his lectures at Cambridge. Religious dissension determined the confessional shape of the Universities under Henry's children, Edward, Mary and Elizabeth, culminating in the Elizabethan Settlement of 1559. Catholics were excluded from many positions and were forbidden to study at the Universities. The narrative features many of the great Tudor names connected with the Universities: Wolsey, Thomas Cromwell, Leicester, Cecil, Walsingham and Cheke. It covers the sacrifice of the Protestant martyrs Cranmer, Latimer, Ridley, Tyndale, Bilney and the Catholic martyrs Mayne, Campion, Nichols, all Oxford and Cambridge men. Intellectual life developed under the first Stuart king, James I, and his Calvinist Archbishop George Abbot but his son Charles I sponsored the Arminian John Laud who rejected key Calvinist beliefs. Resistance to Laudianism ranged from the Great Tew Circle under Lord Falkland and its greatest member, Lord Clarendon, to the Puritan majority in the House of Commons. The Civil Wars ended in the ruination of many Oxford colleges during the Royalist occupation while Cambridge suffered the desecration of its churches and chapels. Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell enforced further reformation of both Universities during the Interregnum. The Restoration restored the status quo ante in which the Laudian Code of 1636 sought to ensure that Aristotle and the other Greek philosophers would hold centre stage in Oxford and Cambridge indefinitely but no classical bulwark could stem the flow of new scientific discoveries. Isaac Newton plunged into the mysteries of 'natural philosophy' (mathematics and physics) at Cambridge in 1661, leading to his annus mirabilis from 1665 to 1666 and ultimately to the publication of his masterpiece, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), 'the Principia'. James II's attempt to turn the Universities into Catholic seminaries resulted in his removal in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, creating new difficulties for the Universities under the Protestant William of Orange and his wife, Mary II. Volume I ends in 1714 with the death of Mary's sister, Queen Anne, the last of the Stuarts, and the arrival of King George, the first of the Hanoverians. The Church remained the chief employer of graduates but it was the Church of England and not the Church of Rome that had prevailed in the religious battles fought under the Tudors and the Stuarts. And it was Parliament and not the Monarchy that held the greater sway over the Universities after their own providential battles for supremacy.

Author’s Note

‘The Heart of Dear Old England’

It is easy to fall in love with Oxford and Cambridge. Whatever else they may be – imperious, self-obsessed, antiquated – they are incurably romantic. Every street is paved with history and a romantic spirit fills the air. You can hear it in the chimes of Great Tom and the Merton bells competing across Christ Church Meadow; you can feel it in ‘the measured pulse of racing oars’ along the Cam; you can see it in the mystical light filtering through the stained glass of the Bodleian. Romance hovers over the Round Church, takes tea at Fitzbillies and meanders along The Backs. It is everywhere.

The Universities’ special position in British life is one of the themes in Thomas Hughes’s novel Tom Brown at Oxford, the sequel to Tom Brown’s School Days. Published in serial form in Macmillan’s Magazine in 1859, it describes Oxford University in the early 1840s. Tom Brown’s friend Hardy (a relative of Nelson’s shipmate, no less) tells the young protagonist, ‘I shouldn’t go so serious, Brown, if I didn’t care about the place so much. I can’t bear to think of it as a sort of learning machine, in which I am to grind for three years to get certain degrees I want. No – this place and Cambridge, and our great schools, are the heart of dear old England.’1

Despite Hardy’s endorsement, there was no escaping the fact that, in his time, the Church of England revelled in its primacy as the Established Church and both Universities were strictly theocratic institutions in which class and wealth were paramount in determining the status of every student who passed through their massive iron-bound gates. Hardy might have been living at the heart of dear old England but as a servitor from an impoverished naval family he had no tassel on his cap and was not allowed to take his meals with his fellow students. Indeed, the nation’s supreme halls of learning were symbols of white male Anglican privilege, and the wealth of preceding generations, whether legally, corruptly or forcibly obtained, had gifted them a rare heritage.

‘It is no good being priggish about this or saying that the earliest colleges were founded for poor scholars,’ the Cambridge historian John Steegmann wrote in 1940. ‘The two universities exist very largely for those who are privileged by birth or income.’ As only communicants of the Church of England were admitted to Oxford and Cambridge in the three centuries following the Sixteenth-Century Reformation, they provided a steady stream of clergymen for the Established Church, as well as conformist doctors, lawyers, teachers, parliamentarians and empire-builders. Many of the Christian explorers, soldiers and administrators who spread British Colonialism around the globe had been exposed to their arcane and intolerant doctrines.2

According to Anthony Wood, the chronicler of late Seventeenth Century Oxford, ‘It is well known that the Universities of this land have had their beginnings and continuances to no other end but to propagate religion and good manners and supply the nation with persons chiefly proficient in the three famous faculties of Divinity, Law and Physics.’ As Divinity supplied vastly more graduates than Law or Physics, the theological studies of its scholars defined the boundaries of orthodox intellectual life.3

Religion was the adhesive that bound families and communities together; it was also the primary cause of great misery and constant warfare. One of the dominant themes of this work is the impact of religious conflict on the Universities and their societies of masters, fellows and scholars. From the medievalism of John Wycliffe and the Lollards, through the English Reformation, the Counter-Reformation and the Elizabethan Settlement to the Civil Wars, the Interregnum and the Restoration of the 1600s, religion was the revolutionary force that turned entire social and political orders on their heads. ‘I would have all reformations done by public authority,’ Elizabeth I’s Protestant spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, decided in the 1580s. ‘It were very dangerous that every private man’s zeal should carry sufficient authority of reforming things amiss.’4

It was, of course, too late for that - the Age of Reformations had already polarised the peoples of Europe as never before. Slowly but surely, the joy, hope and harmony of the Christian message was dissipated under dark shadows of suspicion and intolerance. Even the Golden Rule – ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’ – was trimmed with exceptions. The corroding threads of greed and corruption eroded Christian principles from the holiest to the lowliest as one set of clerics and oligarchs were deposed and another set took their place. The Pope was either the Holy Father or the Antichrist, while Martin Luther and John Calvin were saintly heroes or damnable heretics.

God’s word in one form or another was invoked to reward the faithful and punish the disbeliever. Careers were made or ruined, lives enhanced or lost. Many of the nastiest schisms saw the Universities’ halls and colleges clear out masters and fellows of the opposing faith in brutal purges and rearrange the chapel furniture from Catholic to Protestant and back again at least twice over seemingly futile semantics relating to the points of the compass or different interpretations of Scripture. Personality clashes, donnish vendettas, the male sexist imperative and an inbuilt class system exacerbated religious tensions and led to favouritism and rough justice.

It was inevitable that religious dissension would divert the thoughts of staff and students from the true purpose of a higher education into the cul de sac of religious bigotry and adversarial disputation. The Universities also suffered in other ways, such as the regular culling of books. ‘The forty years of the English Reformation were not encouraging to the prosperity or even the existence of libraries,’ says the historian James Cargill Thompson. ‘The new eagerness of Reformer and counter-Reformer to purge the bookshelves as well as the souls of the nation deprived catalogues of any permanence; the ejection and re-institution of books followed each change of government policy as regularly as the ejection and re-institution of clergy.’5

Following the matriculation statute of 1581, matriculants at Oxford were required to subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England. A similar subscription was required of graduands at Cambridge from 1616 (although after 1772 a Cambridge man who desired a BA degree was allowed to make a simple declaration that he was a bona fide member of the Anglican Church). Under the terms of the 1662 Act of Uniformity, all professors and readers and all heads of house, tutors and fellows were obliged to ‘conform to the liturgy of the Church of England’.6

In both Catholic and Protestant England, Scotland and Ireland, ‘heretics’ and ‘blasphemers’ were executed by hanging, dismembering, burning or beheading for the entertainment of baying crowds. Each death represented an assault on the sanctity of personal faith, while the displaying of heads and severed limbs was an obscene warning to other dissenters. The last victim to be executed for blasphemy, Thomas Aikenhead, a twenty-year-old Edinburgh University student, was hanged at Leith on 8 January 1697 for cursing God, denying the Trinity and scoffing at the Scriptures. Thomas Babington Macaulay said of Aikenhead’s death that ‘the preachers who were the poor boy’s murderers crowded round him at the gallows, and… insulted heaven with prayers more blasphemous than anything he had uttered’.

The 1689 Act of Toleration granting limited indulgence to dissenters was hailed as the final achievement of the post-Reformation religious struggle and yet all nonconformity would be regarded as a crime under the laws of England until 1767, while both Universities would remain closed to Catholics, Jews, Nonconformists and non-Christians. It wasn’t until 1871 that the Universities Tests Act abolished the requirement that those taking lay degrees or holding lay offices should make a declaration of religious belief.7

There has never been a better time to examine the origins and identities of England’s two most famous Universities, both of which are locked today in furious and degrading controversies on the question of free speech and the multiple issues surrounding political correctness, sexual politics and the counter culture. The most serious debate at both Universities in 2023 centred on whether a woman could have a penis. Nevertheless, the wonderful irony of Oxford and Cambridge is that institutions so immersed in the whirlpool of ‘faith’ could have made such extraordinary progress in the field of ‘reason’ and the scientific method of peer review, leading to discoveries that ease the burden of life, cure our ills and enrich the minds of humanity.

My interest in Oxbridge started at school in Australia. Like many secondary schools throughout the Empire the links with the Universities were there from the very beginning. Brisbane Grammar School (BGS), a non-denominational college, was founded in 1869 and its trustees appointed an Oxbridge graduate as our first headmaster. The successful candidate was Thomas Harlin, a large, bearded Irish classical scholar, mathematician and author of books on Euclid and Algebra.

Born at Lisburn in 1834, ‘Tim’...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-5740-2 / 9798350957402 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich