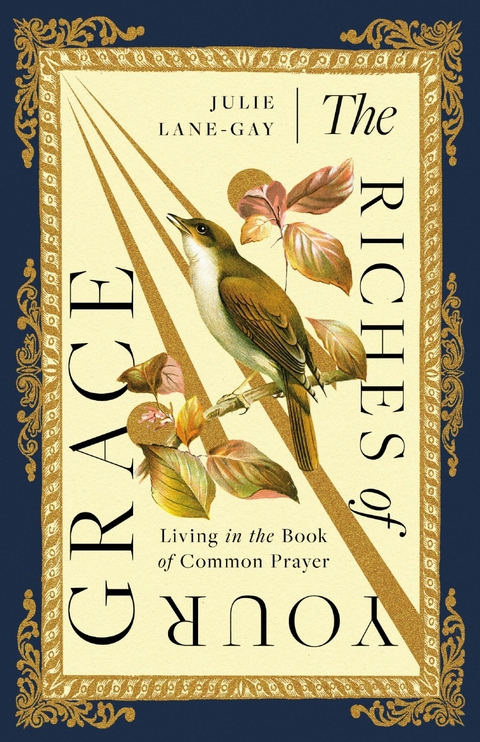

The Riches of Your Grace (eBook)

168 Seiten

IVP Formatio (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0817-1 (ISBN)

Julie Lane-Gay is a freelance writer and editor. Her work has appeared in a range of publications including Reader's Digest, Fine Gardening, Faith Today, Anglican Planet, and The Englewood Review of Books. She teaches occasional courses at Regent College and also edits the college's journal, CRUX. She lives with her husband, Craig, in Vancouver, British Columbia, and is active in her local Anglican church.

Julie Lane-Gay is a freelance writer and editor. Her work has appeared in a range of publications including Reader's Digest, Fine Gardening, Faith Today, Anglican Planet, and The Englewood Review of Books. She teaches occasional courses at Regent College and also edits the college's journal, CRUX. She lives with her husband, Craig, in Vancouver, British Columbia, and is active in her local Anglican church.

1

Morning and

Evening Prayer

I’m late yet again.

I pull in behind the police station (where parking is free on Sundays) and race over to our tall, sandstone church. I wish I’d gotten here earlier to hear the musical prelude. The music quiets me, gives my soul a little breathing room. It’s worth getting out of the house five minutes earlier but I’m lousy at doing that.

The foyer runs along the back of the sanctuary and Tricia, warm and good-humored, opens the side door and hands me my bulletin. I must look sheepish because she shrugs and smiles in a way that says, “Don’t sweat it. You aren’t the only one who is late. You got here.” Her kindness softens me for worship.

The sanctuary is almost full. Soccer moms, university professors, bartenders, and computer programmers fill the pews. There are shorts and ripped T-shirts and dark suits with neckties. Depending on the season, rain boots, Adidas, and flip-flops abound. Like me, these people can be self-absorbed and high maintenance, but when cancer erupts, kids are arrested, jobs are lost, or spouses cheat, they are right there with you.

There are no wood-hewn beams or stone pillars; no stunning stained-glass windows. It’s not the Canterbury Cathedral. The organ is adequate; the piano might be better. The choir is wonderful but there are not a hundred cherubic children in white robes with perfect pitch. With its sturdy tan pews and red carpeting, the sanctuary is comfortable at best. I’ve come to value its ordinariness; it doesn’t inspire awe, but when you track in a bit of mud or a baby cries during the sermon, no one feels like they’re ruining anything. It’s never a performance.

As I move across a middle row to sit closer to the center, I squeeze the shoulders of our friends Michelle and Ben in the pew in front of me and get acknowledging smiles. It comforts me to find them week after week, year after year. I hope I’m that presence for others.

My jacket barely off, the congregation settles back onto the pews as the organ’s last notes of the opening hymn fade. This morning’s service is Morning Prayer, and while the prayer book compilers intended the service to be said daily (and many do say it daily), our church is unusual in that we alternate on Sundays, celebrating Holy Communion on the second and fourth Sundays of the month and Morning Prayer on the first and third. It’s an oddity I’ve come to appreciate.

Some people say the services of Morning and Evening Prayer (together called the Daily Office) each day at home. In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, a number of people at our church gathered online twice a day to say these services together, and they have carried on ever since. They take turns leading and reading the Scriptures. I continue to hear it described as a “lifeline” and a “crucial framework for my day.”

The Daily Office has a deep history. Long before Christ, the Jewish people voiced their prayers of praise and sacrifice in the temple at 9:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m.; they knew that their rituals were what taught and formed them.

Some days at home, I say Morning Prayer by myself. Sitting at the kitchen table or my desk, I read it like a script, saying all the parts and prayers aloud. It was awkward till I got used to it, until hearing the words mattered more than the clumsiness. Some days I don’t get to all the Scriptures; too often I just read the Psalms.

The Daily Office offers a way to shape our workdays and remind us who we are—created, known, and loved by God, people whose work is prayer. It gives us a way to move closer to Scripture’s encouragement to “pray without ceasing.”

Our rector (or head pastor) begins this morning’s liturgy with the Opening Sentence, a call to worship that sets the tone for all that we are about to do. He reads, “I was glad when they said unto me, ‘We will go into the house of the LORD’” (Psalm 122:1). It offers a transition from the parking lot to worship, but it also contains an important acknowledgment. Pastor Tim Challies writes,

The Call to Worship is a means of acknowledging that God’s people come to church each week weary, dry, and discouraged. They have laboured through another week and need to be reminded of the rest Christ offers their weary souls. They have endured another week of trials, temptations, or persecutions and come thirsty, eager to drink the water of life and to be refreshed by it. They have walked another seven days of their journey as broken, sinful people and need to be reminded of who Christ is and who they are in him. Church is urgent business! Instead of being asked how they are, Christians need to be reminded who they are. Instead of being asked where everyone else is, Christians need to be reminded where Christ is.1

Chosen according to the church calendar (or Liturgical Year), the Opening Sentences vary by the seasons of Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Pentecost. This calendar marks our days and months within the eternal rather than the pragmatic. As poet Malcolm Guite says, the church calendar offers a way of “sacralizing time,”2 of shifting us to see Christ’s birth, Baptism, ministry, death, burial, and resurrection both in the past and in our midst.

In the much older versions of the prayer book, the Opening Sentences tended to focus on penitence. Services began with verses such as “I will set out and go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son” (Luke 15:18-19). The intent with this emphasis was to start with the bad news of our sin and set us on the path to repentance and to grace, to remind us that from the outset, absolution and grace are always waiting.

After the Opening Sentences, our rector declares the Call to Confession (some prayer books call this the Exhortation). Before we can praise God, hear His Word, or even thank Him, we need God’s grace, we need the reminder that everything in our relationship with Him comes by His grace. The rector reads:

Dearly beloved, the Scriptures teach us to acknowledge our many sins and offenses, not concealing them from our heavenly Father, but confessing them with humble and obedient hearts that we may obtain forgiveness by his infinite goodness and mercy. We ought at all times humbly to acknowledge our sins before Almighty God, but especially when we come together in his presence to give thanks for the great benefits we have received at his hands, to declare his most worthy praise, to hear his holy Word, and to ask, for ourselves and on behalf of others, those things which are necessary for our life and our salvation. Therefore, draw near with me to the throne of heavenly grace.3

“Draw near with me” is always a bonus. I’m not the only one who came through the sanctuary’s doors this morning immersed in myself.

Sometimes I make a small, silent addition to the ending of the Exhortation—“Lord, show me mine.” I try to make myself ask, “Lord, where have I sinned? What did I do, and what did I not do? Show me where I need to repent.” God’s answers come more frequently than I would expect and often surprise me—a conversation when I wasn’t really listening, a comment in which I tweaked the truth about myself to impress someone. I have come to find it a great sign of God’s love that He shows me my sin when I ask.

While it once was daunting, naming my sins has become a means of grace, a means to know its riches. Sin explains the mess of the world, thousands of years ago and this morning. We aren’t expected to heal ourselves, only to be humble and ask for God’s help. Phrases such as “our many sins and offenses” (in older prayer books it’s our “manifold sins and wickedness”) and “with a humble and obedient heart” now land on me with relief. “Sins” and “wickedness” are countercultural words, but they bring life-giving freedom. They remind me that we live in a thoroughly fallen world, and they pull me again to seek God’s forgiveness.

Some years ago there was a media outcry in the United Kingdom when, in planning his wedding with Camilla Parker Bowles, Prince Charles insisted on keeping this Exhortation in their ceremony, including the words “manifold sins and wickedness.” People were horrified. Surely in light of his earlier affair with Camilla, the prince ought to eliminate the language once and for all, naming the affair as something other than “sin.”

Charles apparently said that to the contrary, this was the right language for their actions, and the best way to begin his new marriage.4

The first time I participated in the service of Morning Prayer, I was visiting to hear a famous preacher. Still happy with the contemporary worship in the church we attended, the set pattern of worship again felt like work. The service guide filled nine pages with small print. Listening to the pastor’s calls and saying the responses, we again seemed to skip some parts and say others. There were hymns and songs at seemingly random times. I worried Morning Prayer would take several hours.

But I also noticed that the scripted dialogue between the pastor and the congregation—the liturgy—was again restful. The service was not about expressing what I was feeling toward God, nor was it about the pastor’s entertaining style. The service’s words and music and dialogue expressed Christ to me, pouring His love and redemption into each of us. Saying the age-old words that carried such scriptural...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum |

| Schlagworte | 1662 • 1662 book of common prayer • Anchor • anglican • application • bcp • Book of Common Prayer • calendar • Christ • Christian • christian living • Church • cranmer • Devotion • Discipleship • Episcopal • Formation • growth • Guide • Intercession • Introduction • Jesus • Liturgy • Memoir • Practical • Practices • Prayer • prayerbook • Prayer book • quiet • Rhythm • Spiritual • spiritual biography • Spiritual Formation • spiritual growth • Spiritual life • spiritual practices • Thomas • Time • Worship |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0817-3 / 1514008173 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0817-1 / 9781514008171 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich