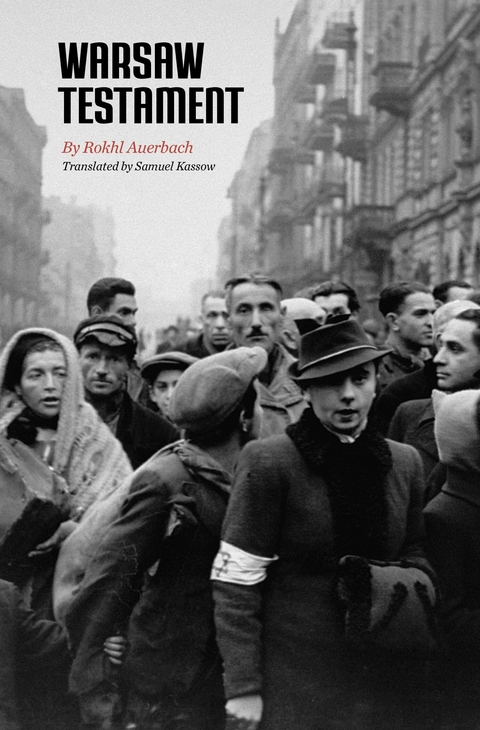

3. MY LAST TIME AT TLOMACKIE 13

September 5, 1939. I was living at Przejazd 1; the poet Nokhum Bomze and the painter Mendel Reif were living in the same apartment. It was now the fifth day of the air raid sirens and the bombing of the city. It just so happened that on Tuesday, the fifth of September, there were fewer alarms than on the days before. That evening Bomze ran in with the still top-secret, terrible news that Warsaw was being evacuated; the army was going to withdraw to new lines of defense and the government was going to leave the capital. Hitler would march in tomorrow, maybe the day after tomorrow.

It was a terrible blow.

Despite the optimistic headlines in the newspaper, we knew that the military situation was bad. Evidently the Germans were using a new kind of technique. They drove deep wedges behind the lines and then used a hurricane of fire and steel to destroy even the most heroic defensive efforts. We knew about the work of the fifth column, which hampered the mobilization and military movement. But still, none of us thought that things were as bad as they were.

We still nursed the fear that Poland—and the other European nations—would seek a new compromise with Hitler.

For years Hitler had blamed the Jews for inciting war, and he warned that they would pay the price. Today we realize that his threats were horribly real. There was a certain truth in his charge that the Jews wanted war. More than anything we were against making peace and giving him concessions. When we saw that war was unavoidable and that there would be no new peace agreement, we all felt a great sense of relief. But we believed too much in the power of the “just war”; we exaggerated its strength.

Jewish soldiers responded to the call of the Polish government and went off to fight with conviction and enthusiasm. We were ready to make the greatest sacrifices. We did not reckon with the danger of a Polish rout and of a German invasion and occupation.

Such a shock could well have broken us, but we did not break. They say that imminent danger sparks the release of a hormone that dulls sensitivity and sharpens the instinct for self-defense.

Someone once remarked that one can think about the Second World War in terms of massive population movements. The immediate reaction to danger is to flee! I saw this during the war, both with the Poles and the Jews. The Germans made it a factor in their military tactics, since a mass flight of refugees blocked major roads and paralyzed the movements of the defending army.

To my great surprise I discovered that I almost totally lacked this instinct to run.

When Bomze delivered his bitter news, he also reported that some room had been reserved for Jewish journalists in the press car of the evacuation train that would leave Warsaw that night. Places would go to those journalists who had the most to fear from the Germans, like political commentators and chief editors.

That night, for the only time during the whole war, I packed a bag and was almost ready to run with the others. Bomze said that there were fifteen places reserved for Jewish journalists, and I naively thought that if there was room for fifteen men, there would certainly be space for a sixteenth journalist—a woman. That’s probably what would have happened had I gotten to that train. Or had I really wanted to run.

It was fated that the Association of Jewish Writers and Journalists would not die in its own bed, in its longtime headquarters at Tlomackie 13.

It all happened about a year or a year and a half before the war. A dispute broke out between the owner of the building and the “impresario” of the association, David Ribayzn. To stir the pot there was the writer Henekh Ash, a member of the governing board. Around that time, after a personal misfortune, Ash tried to distract himself by channeling his energies into the internal affairs of the association. In the event, his maniacal energy earned him the enmity of both Ribayzn and the landlord.

Ash found a very unsuitable building at Graniczna 11. Gala events had been the association’s main source of income, and in this new building the small hall was on the third floor. The building required a lot of work, which cost a fortune. But Ash persevered. He had the walls upholstered with brownish-gold brocaded fabric, installed pretty lights in the windows, and organized a housewarming. Everything was moved to Graniczna, including the priceless archive of literary manuscripts; the collection of portraits, including the large oil paintings of I. L. Peretz and Sholem Asch; and other paintings by Jewish artists that had graced the walls of Tlomackie 13.

The new location on Graniczna was close to the railroad station and to the electric plant on Zielna, obvious targets for German pilots. During the second week of the war Graniczna 11 suffered a direct hit and was totally destroyed, along with the archives and every other trace of the association.

A month later, after Warsaw capitulated and the Germans marched in, people realized what had been lost and bitterly regretted that ill-fated move.

Tlomackie 13 had been synonymous with the association, and that old building emerged unscathed. But even before Graniczna 11 went up in smoke, the bombs had started to fall on Warsaw’s Jewish quarter.

That Tuesday evening, September 5, Graniczna 11 was still standing. I can still remember my visit that evening.

When I showed up with my satchel, the whole building was dark except for two offices. Ber Rozen, the secretary of the literary union, and Y. L. Levinstein, the secretary of the journalists syndicate, were preparing to leave. Using flashlights masked by a blue filter, they were combing through documents and letters. Someone had urged them to make sure that the Germans didn’t get their hands on the lists of members’ names and addresses.

That same night certain colleagues burned books and journals containing anti-Nazi material. Despite the tragic situation, the poet Reyzl Zychlinski could not suppress a laugh when she told me about a certain young poet who, on the night of September 5–6, ripped out each page of his first published book of poems and tossed them one by one into the oven. He thought that as soon as the Germans took the city their first priority would be to barge into his rented room and grab the little book with his anti-Nazi poems.

A group of journalists was standing in the two large rooms, ready to leave. Only members of the journalists syndicate were entitled to a place on the train. Now, as always, “mere authors” were second class. Even among the journalists and editors only fifteen would be able to leave. Yes, there was a list, but many whose names were not on the list turned up with suitcases. Some of them were shouting and became hysterical.

This was the first Jewish “selection.” A bit diffidently, not really sure of myself, I suggested that as the only woman I should latch on to the group. Maybe, once everyone got to the station, there would be room for me too. Now I believe that I was right. In the end more than fifteen journalists left. But my suggestion was brushed aside. A member of the executive committee fobbed me off by saying that “women were in no danger.” Those most threatened should have priority. As the assembled group fought and argued about who should go and who shouldn’t, a few people decided to take their names off the list. The first to do so was Moshe Indelman, who was the head of the journalists syndicate and a co-editor of

Haynt.1 Like the captain of a sinking ship, he did not want to save himself at someone else’s expense. Another

Haynt writer, Aaron Einhorn, also thought it over and decided not to leave. The squabbling gave him a sense of what he could expect in the future. Perhaps his elitist sensibility dissuaded him from becoming a refugee.

I also remember Zusman Segalovitsh. He came carrying only a small briefcase. No knapsack, he said; he would leave with only the briefcase. That gesture soon came back to haunt him. I remember the letters he sent from Bialystok to Ruth Karlinska, imploring her to send him some clothes.

With whom else did I exchange final goodbyes? Somehow, I can’t remember exactly.

The windows of the writers headquarters were wide open, the rooms were pitch black, and the light of an early autumn moon lit up the faces of those leaving and those staying with a deathly, greenish-silvery hue.

The journalists who were going to the train dispersed to say goodbye to friends or to pack some more things. They had to be at the train station at midnight.

Aaron Einhorn’s decision to stay very much affected me. I resolved that I would also stay behind; after all, I would be in good company.

As if on purpose, those who were leaving all gathered together, while Einhorn, his wife, Bracha, and I left the building.

We left at about 10 p.m. It was eerily quiet and the air was fresh and clear. There were no air raids at night. The blacked-out city, the full moon shining over the trees of the Saxon Garden, the lack of traffic—all these combined to create a sense of peace and quiet. The nightmare of our new reality had receded, at least for a while.

I left the Einhorns when we reached Zelazna Brama gate. The Einhorns lived on Mirowska, I at Przejazd 1. On that moonlit night we said goodbye to each other with a sense of relief. We had just experienced a shock and were about to go through new traumas. The deluge was coming closer and...