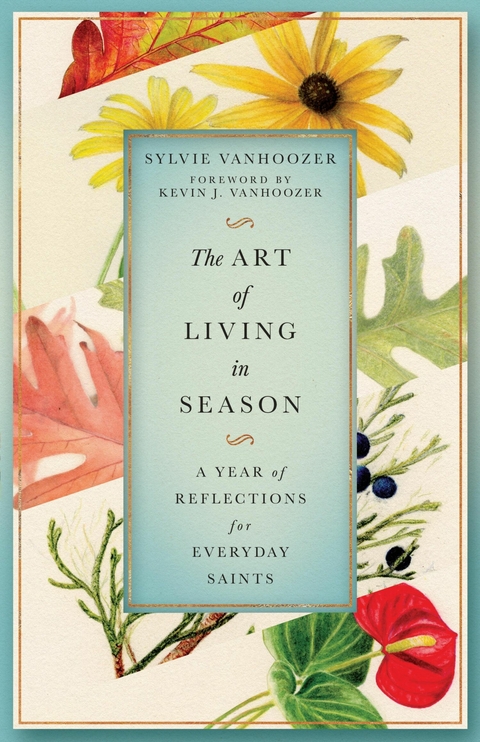

The Art of Living in Season (eBook)

264 Seiten

IVP Formatio (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0697-9 (ISBN)

Sylvie Vanhoozer is a writer, botanical artist, and everyday saint from Provence, France. She lives in Libertyville, Illinois, with her husband, Kevin. They have two grown daughters.

Sylvie Vanhoozer is a writer, botanical artist, and everyday saint from Provence, France. She lives in Libertyville, Illinois, with her husband, Kevin. They have two grown daughters.

Chapter 2

Christmas

The Art of Giving

What can I give Him, poor as I am?

If I were a shepherd, I would bring a lamb;

If I were a Wise Man, I would do my part;

Yet what I can give Him: give my heart.

Then the people rejoiced because they had given willingly, for

with a whole heart they had offered freely to the LORD.

WHERE CHURCH CALENDAR AND NATURE MEET

Our Advent search in solitude was only a preparation for the special season that heralds a new beginning. Noël (Lat. natalis “related to birth” and, by extension, “new”) heralds the good news at the heart of Christmas: a new age has been set in motion by a new turn of events in God’s mysterious plan to rescue humanity. The Son of God enters into human history in the unexpected and thoroughly counterintuitive form of a newborn. In the words of C. S. Lewis: “The rightful king has landed, you might say landed in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in a great campaign of sabotage.”1 In a culture that cultivates consuming, Christmas is a season for learning a subversive practice: giving without return. The traditional twelve days of Christmas celebration already hint at a new order of things. While in nature the land stops giving, the people give more generously than ever—alms to those who lack food, warm clothes for the homeless, toys for the young.

Bright Christmas berries

Outdoors, the earth prepares to sleep; field work stops. Nature bustles outdoor laborers indoors. Plants produce red berries, “as red as any blood.” The berries remind us of the baby’s fate: to die “for us and our salvation,” and to suffer “to do poor sinners good,” in the words of one carol.2 Red berries reminds us that Christmas is after all only one season in the story of redemption, the newness of new life. Europeans think of holly, but having learned the lesson of the Advent walk, I hunt down holly’s local counterparts: American yew, viburnum, wintergreen and winterberry bushes. Fittingly, the symbol is there for all who have eyes to see, even those who are far from Bethlehem or Provence. Meanwhile, evergreens stay green in the bitter cold, a reminder that nature is not dead, only dormant. Nature will awaken; spring will spring again.

CHRISTMAS COMES TO PROVENCE

As we have seen, in the land of the santons the carols speak of Bethlehem as if it were in Provence. The way the Provençaux tell the Christmas story, when the angels proclaimed to the shepherds in the hills, all the inhabitants of the neighboring countryside heard something too—rumors of a wondrous divine birth and, for some reason they cannot fathom, they felt a sudden urge to undertake what the carols call a “pilgrimage.” This was despite the bitter cold and dangers of paths riddled with brigands and wild animals. One pastorale hints that these inklings or prompts originate with God who is in high heaven, directing the earthly pageant down below.3

In the world behind the crèche, those keeping watch over the manger are biding their time, waiting for the right moment, late on Christmas Eve, to place the figure of the baby Jesus between his parents. Other little saints in the surrounding countryside also begin to inch their way toward the manger, helped along by eager little fingers. Eventually, the children reluctantly retire to bed, leaving the little saints to journey on into the night, only to discover, the next morning, a marvel: the figurines have all arrived at the manger after their nightlong journey! This is the signal for which the children have been watching and waiting. Gift-giving time is upon them, in the crèche, and in the home. Joyeux Noël! As the santons lean in with their gifts, so close to Jesus that one can barely see the baby, the families beyond the manger act out a similar scene with their own children.

THE SEASONAL SANTON

Le tambourinaire (the drummer)

Those santons whose gift is music set the tempo as we enter the scene. The Christmas story opens with “a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying, ‘Glory to God in the highest!’” (Luke 2:13-14). And yet, in traditions the world over, the angels do not simply say but sing the words, and they are typically portrayed in paintings (and Christmas cards) with musical instruments. It’s no surprise, then, that the way the Provençaux tell the story of Jesus’ birth incorporates music played on traditional Provençal instruments, carved out of local wood by some little saint, perhaps a luthier, a craftsman with a special vocation; he does not make music himself, just the instruments others use to make music.4

The musicians play a crucial part in the traditional Christmas plays of Provence. They follow hard on the heels of the angels and shepherds, leading all the little saints who set off to see the baby in Bethlehem like so many pied pipers. Like the virgins of ancient Israel, they adorn themselves “with tambourines / and shall go forth in the dance of the merrymakers” (Jeremiah 31:4). The tambourinaire is a well-known santon figure who plays the drum with one hand and the galoubet (a three-holed flute) with the other.

MUSICIANS IN PROVENÇAL CULTURAL TRADITIONS

Probably one reason why Christmas angels are always represented with instruments (trumpets, harps, and more) is that words are not enough to express the joy of this awesome moment. Music steps in when mere words stop short, failing to communicate the glory. Words need music to amplify the message; music needs words to clarify it. In the traditional carols, the music comes with lyrics. The singers express what every little saint in the crèche is thinking. The pastorales are, for lack of a better term, Christmas musicals with a twist: the characters wonder about their gifts, and what their lives are for. If this is the Son of God, then what can I bring him? Desperate for ideas, they ask their neighbors: What are you giving him?

The answers are simple, consistent with the common and comical style we encountered in Advent with our shepherds. In the traditional noëls, most villagers decide to bring something from their daily table fare.5 But then, something like the miracle of the loaves and fishes takes place: their meager donations of bread, honey, eggs, goat cheese, grapes, cake, fresh fish, and stews in cooking pots eventually become a veritable feast laid at the feet of Jesus, mirroring the feast that is being prepared beyond the crèche around family tables. Meanwhile the village women, who are used to dealing with the practicalities of new births, bring up the necessity of fresh “diapers”: Is anybody else thinking of straw for the baby? A woman, presumably a midwife, brings a wooden cradle with fresh linens. The noëls allow the characters to give voice to these minor concerns. By song’s end, each little saint has come up with an idea of what he or she has to offer the infant King.

As the pilgrim-villagers gradually make their way toward the manger down through the hills of thyme and juniper, across the fields, and over rivers, they eventually meet fellow pilgrims at various crossroads, making the company of little saints larger and larger—and louder and louder as they come singing and dancing. The full-size everyday saints who watch the procession sing the songs as well. Some may identify with their miniature counterparts who ask, “What can I bring him?” This may simply be another way of asking, “What is my role in the story of Christ?”

Nicholas Saboly, who composed early noëls in the 1600s, used his music to express life’s questions in song as a way of helping the carolers think about how to live out their faith in their own places. The question had to do with the meaning of existence, but this was not existentialism. Rather, it was the question Christina Rossetti poses in her Christmas carol: “What can I give Him, poor as I am?”6 Saboly’s gift was to use his music not simply for entertainment but also edification. He wished to rekindle people’s devotion to Christ in their everyday by expressing in his lyrics how they might use their gifts for Christ in their home of Avignon. Jesus is the center and the soul of Saboly’s carols, but he comes wrapped in Provençal swaddling clothes to remind the people that their gifts are very much enmeshed with everything else they do and love. Provençal author Frédéric Mistral, who rediscovered Saboly and transcribed his songs in the 1800s, wrote about him in glowing terms: “As for men like Saboly, there is no more need to talk about their lives than you would a nightingale, or a cicada: their life is in their songs, for they spend their lives singing.”7

The tambourinaire and companion musicians represent the gift of song. Their songs have become part of the local culture, reminding us that music is not just for special occasions like Christmas but adorns the everyday. For there is something to sing about not just during Christmas season, but all along the everyday saint’s pilgrimage: celebrations of life and death,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Kevin J. Vanhoozer |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum |

| Schlagworte | Advent • botanical illustration • Christian Spirituality • Christmas • church calendar • Devotional • Lent • Memoir • nativity • nativity scenes • Nature • nature memoir • Ordinary time • Provence • Saints • Santons • Seasons • South of France • spiritual memoir • weekly Devotional |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0697-9 / 1514006979 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0697-9 / 9781514006979 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich