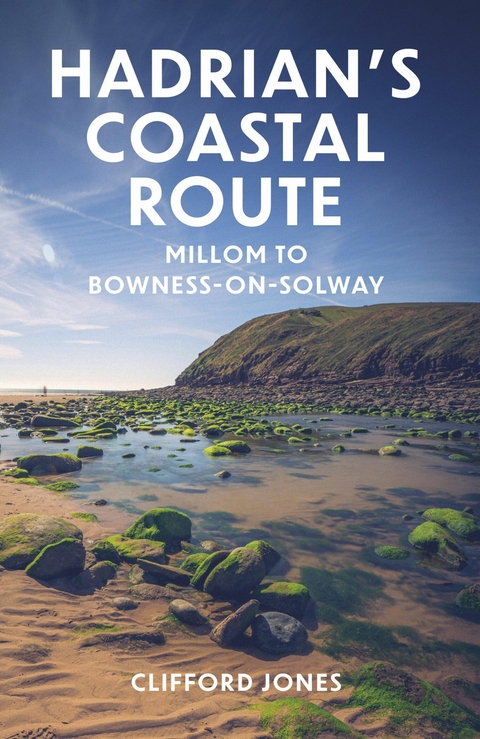

Hadrian's Coastal Route (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-635-6 (ISBN)

CLIFFORD JONES is an archaeologist and lecturer who has spent over thirty-five years researching the Roman occupation of West Cumbria. He is a passionate supporter of Community Archaeology, Real Ale and Real Pubs, and a commercial member of Cumbria Tourism actively encouraging people to visit the gems of the western coast. He is also a Board member of the Council for British Archaeology (North).

A Western Frontier

From a modern perspective, the heritage of the Western Frontier has been managed as a series of islands of interest down the West Cumbrian coast.

Ravenglass Fort and Bath House

Moresby Fort

Burrow Walls Fort

Maryport Fort and Environs

Allonby Bay Mileforts & Towers

Bowness-on-Solway Fort

The word ‘frontier’ is rarely used regarding the Cumbrian coast, but seems appropriate in the very straightforward sense of the coast being a geophysical line between land versus sea. So, a frontier it is!

A frontier suggests a need for a barrier, but it seems not to be a feature of the early advancement of Rome in the North West, and there appears to be no evidence of native coastal defences to stop the Romans arriving by sea. The Hadrianic constructions (AD 122) seem to be the most likely date for the works down the coast as well. There is no point in a barrier unless you protect the ends, otherwise people will just go around it! This poses the question of why the original Wall stopped at Newcastle upon Tyne and had to be extended further east to Wallsend and Tynemouth. But the whole endeavour is full of question marks.

The Cumbrian side is narrower compared to the Northumberland side, and the lack of good stone saw a turf and wood barrier on the Cumbrian side – a style that seems to have remained popular between the western forts down the coast. If nothing else, the Romans were practical and flexible to circumstances. It also highlights that the frontier altered over time. Ireland and Scotland may have seemed a greater threat from day one, whilst the eastern tribes had been subdued and no immediate threat remained, so there was no reason for enclosure. Much later, the east was no less under threat of incursion, resulting in watchtowers further down the east coast – by which time much of the western coast was under less immediate threat.

The reader must consider that the Solway and the Cumbrian coast is a highway and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to stop every vessel from plying these waters, and so ideas travel as well as goods. The limitations of a frontier are apparent, as information and learning are universal; the Cumbrian coast would likely always have been a hotbed of political change.

Forts at key strategic river and coastal locations have more to do with the culmination of good long-term planning, exploiting the well-established trading links to maintain control of that trade, rather than the prospect of an invasion.

The Roman fleet, the packhorse of the Roman Army, required drinking water. Pure sources were required to keep the sea lanes open and the numbers of wells at Ravenglass are testament to this theory, and the pattern is repeated throughout the early coastal military establishments – good water close to the sea.

Once the Romans were fully established, fort locations offered the opportunity to tax vessels as they passed by. The Roman Empire relied on an efficient taxation system to maintain the status quo.

The list of heritage sites mentioned above is only a fraction of the likely actual material remains.

The walker can pose the question:

If the physical remains of Roman coastal watchtowers, mileforts and palisade ditches are traceable from Bowness-on-Solway to Maryport, does the system reach all the way to Ravenglass?

The answer is yes. Archaeologists are by nature cautious, and rely on evidence. There is just enough to suggest a constant, if irregular, barrier.

The reasoning is, if the contrary presumption is considered, that there is only a need for a physical ‘side’ to Hadrian’s Wall to protect against an attack between Bowness-on-Solway and Maryport. This would expose Workington and its river, which offers potential for deep incursion into the hinterland.

It is very unlikely that the low-lying ground from Maryport to Workington was left so exposed, with only the fort at Burrow Walls to stop incursions.

There seems to have been a need to be seen to be administering a system of control, rather than to be constantly patrolling the coast, suggesting that there were only occasional forays from tribes outside the Empire attempting to exploit its wealth. At least until the second century ad.

WHY STOP AT RAVENGLASS?

Whilst there is an apparently excellent means for an army to get inland via the River Esk, going further east than Hardknott would be impossible and the terrain to the north has limited routes via the Fells, all of which would be death traps. If an army attempted to turn immediately north after landing along the coastal strip, this would be met with opposition at Ravenglass and Moresby: the Fells are too rugged for a military force to pass unopposed, unlike the scenario at Workington, where the terrain is much gentler.

Active archaeological research between Ravenglass and Maryport continues apace to confirm a physical frontier. A hopeful sign is the recently reported discovery of a very deep ditch ‘with wood at the bottom’ running between Saltcoats and Drigg.

A THEORETICAL (BUT HOPEFULLY PLAUSIBLE) SCENARIO FOR ROMAN ARRIVAL

Imagine the scene during the last days of the Roman Republic. Marcus Tullius Cicero is busy prosecuting in Rome; meanwhile, the tide is lapping at a small trading vessel’s bow as it arrives at the quiet native harbour of Ravenglass in the far-off land of mists beyond Gaul.

The beach is a No Man’s Land; no one can truly call it their own, so trade takes place on this margin. Nobody feels as if they are being invaded when the sea reclaims it and all parties can put distance between each other quickly. There is nowhere to hide, so it is a place to meet strangers.

As long as no sword is drawn all is well, and this is the case as the parties greet each other with a mutual interest in commerce. The trader soon learns of good water sources, mineral wealth, what crops are grown, who is in command and who the natives’ enemies are.

This process is repeated time and time again, and eventually a series of trading bases are set up with trustworthy local chiefs easily pacified by quality Roman products, such as good wine.

The trader’s profitable return to his home base in Gaul creates interest from his fellow traders and this commercial inquisitiveness encourages others to consider exploration and exploitation. From Gaul, the trader’s findings eventually reaches Rome; aristocrats, already accomplished at doing business with barbarians, are well-placed to consider investment in further expeditions into the far North West, and to protect their interests they provide traders with mercenary forces.

Back in Ravenglass, cordial relations continue between the natives and the trader and his compatriots; time passes and the next generation of the trader’s family continue the cycle. Sailors and traders have further cordial relations with the native women and the social control of the native settlement begins the process of Romanization. Trade prospers, the knowledge and skills of some of the natives increase, and the enslavement of other groups is a profitable occupation, allowing for even more good living.

Such profit requires protection and the traders (for more have arrived) are allowed to construct suitable secure enclosures for their goods. The locals allow access to the hinterland; the source of the local wealth, be it agriculture, minerals or a mixture of both, is now open for thorough exploitation.

Time passes, as it tends to do. The Republic falls, the Imperial Age arrives, and the Emperor Claudius, needing to legitimise his control of the Empire (having removed his predecessor Caligula) by gaining a swift and effective victory over something and someone, and urged on by his tradesman friends eager to get into a market that had previously been the sole realm of aristocrats, stamps his mark by doing so in AD 43.

With Rome firmly established in Britannia, the gates for trade were thrown open and information, previously in the hands of the few, are suddenly available to the many. It is boom time, but after boom comes bust and the local chieftains found themselves in severe financial difficulty. They attempted to throw the Romans out and nearly succeeded, resulting in a heavy Roman military presence and a desire to control all parts of the island to prevent further revolt.

As a result of several generations of trading contacts, the increase in official military activity in the north of Britannia meant that the contacts to date were seen as valuable military intelligence. A wider understanding of the territory and peoples is crucial information for Gnaeus Julius Agricola, based at Chester, preparing for military forays into the far north.

A picture of the wealth of an entire region, its geography and demography was easily established; the allegiances and enemies known. All this makes a military occupation so much easier. A small fortlet was set up close to the harbour facility at Ravenglass – the Romans had arrived.

Such measures were undertaken without revolt, as many of the locals were very compliant; firstly, because they liked the Romans and the fine goods, and secondly, because the superior tribe of the region, the Brigante, were in the middle of a civil war against their own leaders, and it was deemed extremely useful to have a superior military force’s protection.

This was a situation which exacerbated the fall of the strategic border capital, Carlisle, into Roman hands very early in the Roman military campaigns – led by Quintus Petilius Cerealis, who was in command of a vexillation of Legio IX Hispana in advance of Agricola’s seaborne...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Walker's Guide | Walker's Guide |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte | |

| Schlagworte | hadrian's wall heritage trust ltd • manned bases • mileforts • ravenglass to bowness-on-solway • Roman Forts • walker's guide • Walking Guide • Wallsend • watxhtowers • western frontier |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-635-8 / 1803996358 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-635-6 / 9781803996356 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 23,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich