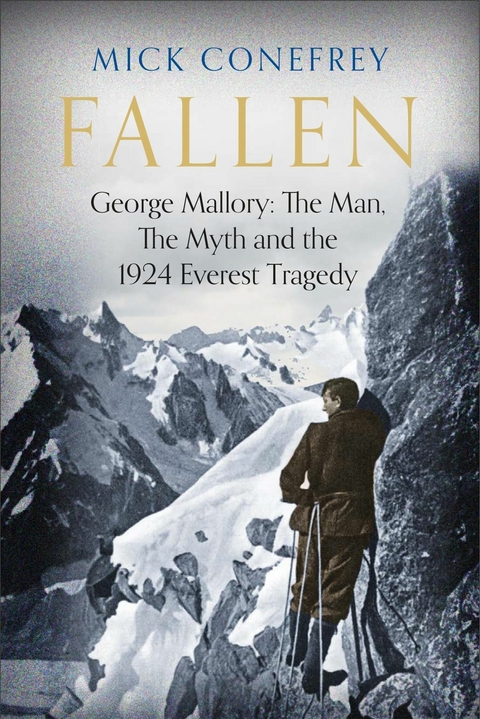

Fallen (eBook)

352 Seiten

Allen & Unwin (Verlag)

978-1-83895-980-7 (ISBN)

Mick Conefrey is an award-winning writer and documentary maker. He made the landmark BBC series Mountain Men and Icemen and The Race for Everest to mark the 60th anniversary of the first ascent. His previous books include Everest 1922, Everest 1953, the winner of a LeggiMontagna award, The Last Great Mountain, the winner of the Premio Itas in 2023, and The Ghosts of K2, which won a US National Outdoor Book award in 2017.

Mick Conefrey is an award-winning writer and documentary maker. He made the landmark BBC series Mountain Men and Icemen and The Race for Everest to mark the 60th anniversary of the first ascent. His previous books include Everest 1922, Everest 1953, the winner of a LeggiMontagna award, The Last Great Mountain, the winner of the Premio Itas in 2023, and The Ghosts of K2, which won a US National Outdoor Book award in 2017.

2

Go West

Lee Keedick thought he had a nose for a winner. Square-jawed and determined-looking, he was a former college baseball player from Iowa who set up a public speaking and press agency in New York in 1907 and kept it going until he was well into his seventies, billing himself as the ‘Manager of the World’s Most Celebrated Lecturers’. In the early 1900s, when the cinema was just getting going and television was a mere pixel in John Logie Baird’s eye, there was a thriving lecture circuit all over the US, and audiences would come in their thousands to hear the famous men and women of their day tell their stories.

Initially Keedick’s clients included American union leaders, magicians and big game hunters, but gradually he built up two specialisms: first, explorers such as his friend Roald Amundsen, the first man to reach the South Pole; and second, British personalities, ranging from the aristocratic Countess of Warwick, who lectured America on ‘British Traits’ in 1912, to famous writers such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H. G. Wells and G. K. Chesterton, who visited America in the early 1920s.

In the autumn of 1922, Keedick tried to bring those two specialisms together when he contacted the Everest Committee in London, inviting them to send a member of the recent expedition over for what he promised would be a lucrative lecture tour. It would be a big hit, he assured them, as long as the British chose someone who could tell the story ‘in popular style to arouse public interest’.

The Everest Committee had no doubt that George Mallory was the right man for the job and he readily agreed. Honorary secretary Arthur Hinks didn’t like the fact that Keedick wanted to take 10 per cent more in commission than his British counterpart, Gerald Christy, but he was keen to raise money and the next expedition’s international profile.

So, in January 1923, Mallory set out for New York on the RMS Olympic, the pride of the White Star shipping line. It was Keedick’s idea that he should travel in style, taking the Olympic rather than one of the cheaper ships Hinks would have preferred. If America was going to embrace Mallory as a star, Keedick maintained, he would have to play his part and behave like one. Mallory did not object. After spending much of the previous two years sleeping in a tent on the windswept plains and slopes of Tibet, the five-day voyage was a no-holds-barred immersion into the world of luxury.

The Olympic was a sister ship of the Titanic and at one time the largest passenger ship in the world. It had a swimming pool, gymnasium, Turkish baths, and several restaurants and bars. Initially, however, Mallory preferred to keep himself to himself, spending much of his time in his cabin, reading and writing. It would be his first visit to the United States and he was eager to see New York, visit Niagara Falls, and if everything went well, go as far west as California. The only downside was the people.

Like Charles Dickens, who had visited the US in 1842, initially Mallory was rather a snob about his transatlantic cousins. The first Americans he got to know were his nightly dinner companions on the Olympic, a family of tourists returning home after spending time in Europe. As he wrote to his wife Ruth, they were kind-hearted but naive. The husband in particular had ‘disgusting’ table manners and an accent that verged on caricature. At first Mallory could barely understand them, or they he, but gradually he tuned into their way of speaking and began practising his American accent, hoping that it would be of use when dealing with porters and ‘such’.

Mallory’s main preoccupation was to get as much writing as possible done for the official account of the 1922 expedition. His target was 2,000 words a day, but though he was happy to immerse himself in the details of his recent expedition on paper, he was not so keen on being recognized by other passengers. He kept off the subject of Everest with the American family, and managed to stay incognito until he bumped into a British general and his wife, who as luck would have it, had been on the SS Narkunda, the P&O ship that Mallory had taken back from India five months earlier. Fortunately, General Hughes was the soul of discretion and kept Mallory’s secret safe. A few days later, on 17 January, the Olympic reached New York.

It was a bright, blue-sky morning but, fittingly, freezing cold with a vicious wind that reminded Mallory of Tibet. The Olympic anchored for a few hours just off the Hudson River while passports were checked, and then steamed past the Statue of Liberty into the New York docks. Like many before him, Mallory was immediately struck by Manhattan’s skyscrapers, but he was probably the first to view them with a mountaineer’s eye, describing the spearhead of tall buildings at the tip of the island as ‘one of the most wonderful effects of piled up mass I have ever seen’.

Once the ship had docked, Mallory was whisked way to the Waldorf-Astoria, then New York’s most prestigious hotel, and installed in a large room on the tenth floor with its own telephone and a luxurious bathroom. Keedick didn’t give him much time to settle in: almost immediately he was introduced to a press agent, who briefed him on what to say and then hustled him into a room full of journalists.

American newspapers had followed the story of the British reconnaissance of 1921 and the second expedition a year later, but though Mallory was the best-known member of the British team, he was not nearly so well known as Amundsen or Shackleton. Arthur Hinks and the Everest Committee had always been uncomfortable with publicity, viewing newspapers as a necessary evil. Hinks trusted The Times, considering it a ‘newspaper of record’, but was very sniffy about other publications and was always uncomfortable with personalizing the expedition or creating any heroes.

The next day, the New York Times carried the first of several articles it would run on Mallory over the next three months. Under the headline ‘Says Energy Faded on Everest Climb’, it told how he had reached 27,235 feet (an exaggeration that would be repeated many times in the US press) but had turned back fourteen hours from the top when he and his party felt their physical and mental strength giving out. ‘Would Everest ever be climbed?’ the reporters had asked. ‘It’s a gamble,’ said Mallory, tight-lipped.

Three years into Prohibition, American journalists were particularly keen to hear whether the climbing party had taken any ‘alcoholic stimulants’ and Mallory duly obliged, admitting that though the medical advice was against it, he and his partners had swigged back a little brandy at high altitude ‘with good results’. The New York Times underestimated Mallory’s age by six years and elevated his schoolmaster role at Charterhouse to that of a full-blown professor, but it was a positive start and the article mentioned his forthcoming lecture tour twice. There was less good news, though, from Keedick.

Despite his bullishness the previous autumn, it turned out that very few lectures had been booked. There had been many enquiries but hardly anything had been firmed up. Everything, Keedick said, depended on Mallory’s first New York lecture, at the Broadhurst Theatre in early February. If he did well and got good reviews, the bookings would come in. If not… Keedick didn’t elaborate. Prior to the Broadhurst, Mallory was engaged for some warm-up lectures in Philadelphia and Washington, but until then, Keedick advised, he was free to enjoy the Waldorf and two private New York clubs where he had been given temporary membership.

It was disappointing and slightly surprising, but Mallory was glad to be in America, and though he worried that he didn’t know many people, in fact it turned out that he had several relatives and acquaintances on the East Coast. He still hadn’t finished the chapters for the Everest book, and was keen to rework the British lectures that he had recently given to American tastes. He even hoped that he might have time to find an American publisher for his book on James Boswell.

A week after his arrival, Mallory left New York for the first of two lectures for the National Geographic Society in Washington. The venue was the Masonic temple, a large Neoclassical building that was a distinctly grander stage than the provincial British theatres Mallory was used to. Keedick resented the fact that the administrator at the National Geographic Society wanted Mallory to deliver both an afternoon and an evening lecture but was only willing to pay a single fee, but it was a good platform, especially as Mallory was going to be introduced by Robert Griggs, the famous American explorer and botanist who had made a daring visit to the volcanoes of Alaska.

Once enough hands had been shaken and publicity photographs snapped, Mallory began his lecture with a simple but provocative question: ‘What is the use of climbing Everest?’ His answer was succinct: ‘It is of no use.’ Reaching the summit of the world’s highest peak, he declared, had no ostensible scientific value but was a product of the ‘spirit of adventure and of pitting human intelligence against natural objects’.

Over the next hour, Mallory told the story of the 1922 expedition and the previous year’s reconnaissance, illustrating the various stages of the journey and the two main attempts...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Schlagworte | Andrew Irvine • Everest • George Mallory • Mick Conefrey • Mountaineering • Wade Davis |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-980-7 / 1838959807 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-980-7 / 9781838959807 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich