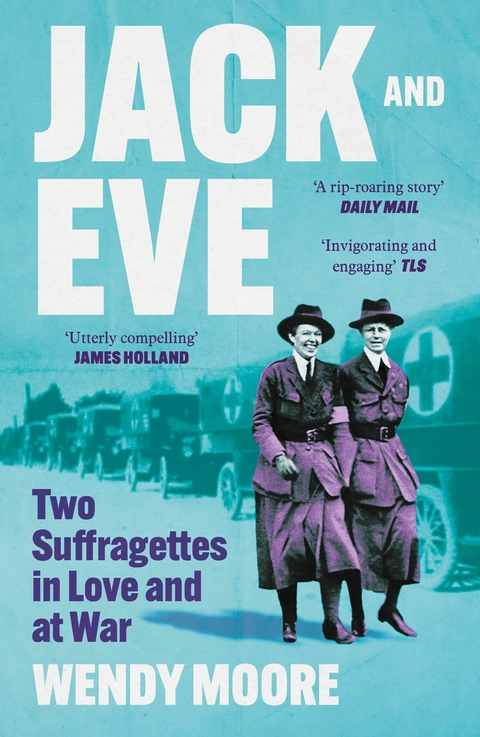

Jack and Eve (eBook)

400 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-810-7 (ISBN)

The First World War paused the suffragettes' campaign and Jack and Eve enrolled in the Scottish Women's Hospital Service and soon found themselves in Serbia. Eve set up and ran hospitals for allied soldiers in appalling conditions, while Jack became an ambulance driver, travelling along dirt tracks under bombardment to collect the wounded from the front lines.

Together, they carved radical new paths, demonstrating that women could do anything men could do, whether driving ambulances, running military hospitals, becoming prisoners of war or bearing arms. They refused to compromise in their sexuality - they were lifelong partners even though Jack enjoyed relationships with other women. Determined to be themselves, 'forthright, flamboyant and proud', Wendy Moore uses their story as a lens through which to view the suffragette movement, the work of women in WWI and the development of lesbian identity throughout the twentieth century.

Wendy Moore is a freelance journalist and author of five nonfiction books on medical and social history. Her second book, Wedlock, was a Channel 4 TV Book Club choice and a Sunday Times no 1 bestseller. She lives in London.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 32pp plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Gender Studies | |

| Schlagworte | ambulance driver • androgyny • Evelina Haverfield • Lesbian • lesbian history • Lesbians • LGBTQ+ • LGBTQ+ history • military hospital • Pankhursts • queer history • Suffragette • suffragettes • Sylvia Pankhurst • thruple • Vera Holme • woman chauffeur • woman driver • Women in WW1 • World War 1 • WW1 |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-810-X / 183895810X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-810-7 / 9781838958107 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 851 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich