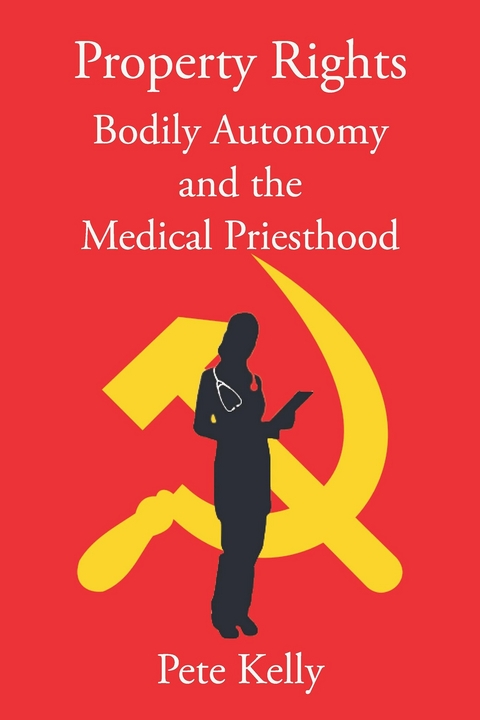

Property Rights Bodily Autonomy and the Medical Priesthood (eBook)

314 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-0434-5 (ISBN)

Recently, bodily autonomy has come under attack. The debate over whether individuals have the right to make decisions when it comes to their own bodies has been raging at the dinner table, online, and in the workplace. Government mandates requiring social distancing, masking, and vaccinations have caused deep divisions in society, forcing millions of people to understand and explain how these mandates violate their inalienable rights. Since the beginning of recorded history, two great pillars of every thriving society have been bodily autonomy and the ability to own property. Revering human life and private property as sacred blessings of divine origin, ancient societies arranged their systems of governance for their protection. As our minds and souls inhabit our physical bodies, the ancients believed that our bodies were intended to inhabit physical territory enabling security, prosperity, and virtue. With the assurance of these immovable pillars which would eventually become known as natural rights, individuals would be incentivized to make public contributions of increasing value through land ownership. However, the failure of governments to protect either of these rights has always been accompanied by the loss of both. This book will equip readers with the Moral, Religious, and Constitutional origins of bodily autonomy by exploring how inalienable rights have related to religious and government authority throughout history from the earliest civilizations to the present day, through the lens of property ownership. This book will also explain how to apply the principles of Protestant Resistance Theory in the 21st century with the understanding that our bodies are not property of governments, kings, or human institutions, but of the Living God.

Chapter 1

Theft and Ownership

Theft without ownership

is like weather without the sky.

– Unknown

Theft

The marginalization and blatant denial of objective reality has occurred throughout history, especially when it is oppositional to an agenda. A tactic used to diminish the authority of reality is to label phenomena as social constructs, allowing empirical truth to be approached with the presumption of good faith with while maintaining impunity from underlying ambivalence, prejudice, and malevolence. Considering the notion of theft, we could deem it a social construct which would thus be subject to deconstruction. Theft could be construed as Not-Theft if a prosecutor argued with effective wordsmithing. But could the concept of theft be completely removed from human consciousness if a lawyer successfully persuaded a judge?

Theft is not created by laws, nor is it something that emerges from a social agreement. Theft existed before intellectual property law. It existed before every toddler was able to tearfully express their loss when a favorite toy was commandeered by an older sibling. It’s what compels us to declare, “That was my idea” and, “That’s my toy,” without any knowledge of legality. Theft isn’t a social construct; It’s an objective moral reality. When we have been unjustly deprived of something that is “ours”, we don’t need revised statutes to tell us. We know it. We know it, first, because we feel it. When have you felt a sense of loss? Not the kind of loss you feel when you drop your wedding ring over the side of the boat into the lake. Or the kind you feel when your 30-year-old car finally breaks down for the last time. Not the feeling of being defeated by an athlete who was truly better than you. Or the feeling of losing the 1980 presidential election to a Hollywood actor-turned-politician who decidedly outwits, out-debates, and out-jokes you into a humiliating defeat.

I mean, the feeling you get when your wedding ring gets pulled off your finger in a crowded market. The kind of loss you feel when you walk out of the concert venue and your car windows are broken out, the tires have been removed, and the stereo is gone. The feeling you have when your womens’ swimming competition is won by a man pretending to be a woman. Or the feeling of waking up on November 5th after seeing your commanding electoral lead paused late in the evening only to be followed by sudden deliveries of mass-produced ballots, partisan-fueled denial of access to polling places, vote switching, and vote duplicating under the pretenses of social distancing to prevent the transmission of a well-timed novel corona virus.

These are different feelings of loss. One is a sense of sadness accompanied by an understanding that things wear out, accidents happen, and sometimes you get outperformed. And the other kind of loss includes a sense of righteous indignation from being deprived of something that rightly belongs to you. But is feeling the sense of being deprived of a possession enough to validate the existence of theft? If theft was only a social construct fabricated without absolute and objective principles of justice, our feelings of violation and impulses to complain would not be objectively justifiable. At most, we would simply possess things only for as long as we needed them, then give them to someone else who needs it. But even then, imagine how would we feel if something we possessed was taken by someone else before we were done using or – heaven forbid – enjoying it. Would we still call that theft? Or would we give it a bigger, fancier name like, Collectivization. Would calling it something else make it feel different? Would a name make it Not-Theft?

Let’s try this thought experiment with other actions. Rape, for example. Would the victim feel better about it if we called it Affirmative Affection? Let’s try with murder: Accelerated Lifespan. Better yet, Terminated Pregnancy. How about kidnapping: Custodialization. Yes, I made all of those up, except one. Regardless of what we call things, they are what they are. And theft exists regardless of the name we give it or the rationalization we use to excuse it. Theft is an objective moral reality which has been identified and whose prohibition has been codified by nearly every human society. Proof of its existence can be found in a wealth of documentation prohibiting its occurrence and establishing penalties for it. Hammurabi’s Code pronounces:

If anyone breaks into a house to steal, he will be put to death before that point of entry and be buried there.

If anyone is caught while committing a robbery, then he or she shall be put to death.

If the robber is not caught, then shall the one who was robbed claim under oath the amount of his loss; then shall the community on whose ground and territory and in whose domain the robbery occurred compensate him for the goods stolen.

Ancient Hebrew law took a clear position on theft and trespassing:

You shall not steal.

Do not move the ancient boundary or go into the fields of the fatherless.

Islamic Law prohibits theft in the Quran:

O Prophet, when the believing women come to you pledging to you that they will not associate anything with Allah, nor will they steal.

Habachy states:

It is no mere coincidence that the Arabic word for boundaries is Hudud, which is precisely the term the Qur’an uses to define the “rights of God” (Hudud Allah), the trespass of which constitutes what the old French criminal law termed Crimes de Lese Majeste Divine. According to the commandments of the Qur’an, severe punishments must be administered by the Imam for five of these crimes. Highway robbery and theft are two of them. The penalty for the first is death. A thief is punished for the first offense by amputation of the right hand; for the second offense, the left leg is cut off. In the event of further recidivism, the punishment is death.

The Etruscan law, speaking in the name of religion says:

He who shall have touched or displaced a bound shall be condemned by the gods; his house shall disappear; his race shall be extinguished; his land shall no longer produce fruits; hail, rust, and the fires of the dog-star shall destroy his harvests; the limbs of the guilty shall become covered with ulcers, and shall waste away.

From the start, we see ancient law invoking divine sovereignty to prohibit theft. For the ancients, theft was not a social construct, but rather an offense to the gods. In some tribes such as the Naga of Myanmar, theft was punishable by fines, beating, and even death. A cynic might say that there are many examples of ancient peoples who didn’t perceive theft as a moral transgression. The ancient Egyptians, for a time, established an organized system of theft under authorities who would duly restore the property to the owner on payment of a portion of its value. But most people would see this as a system of extortion. If the civil authorities received economic benefit through the recovery of an individual’s property, what incentive would there be to prevent theft from happening in the first place? A similar de-incentivization presently occurs within the modern pharmaceutical industry. If members of the medical establishment make money from sick people who continually need medicine, there is no incentive for the establishment to discover cures for disease whose perpetual management is highly profitable.

But even in ancient Egypt, as in other societies, theft was largely seen as a delinquency that individuals would treat with vengeance, but authorities treated with justice. Groups understood that the owner, surprising the thief in the act of carrying off his goods, would naturally attack, and very likely kill him. Thus, societies also understood that law had to be established so that, if the owner did not find the thief, he ought to be thankful if custom allows him to get restitution, with perhaps something more, for his suffering.

When we combine the universal feelings of unjust deprivation with penalties grounded in the moral framework of religion to prohibit their occurrence, we can see humankind agreeing to the existence of theft, not only a civil offense, but as a moral transgression against the divine origin of Ownership. The only way theft can occur as a moral transgression is for property ownership to also have an objective moral justification. Simply put, theft offends God.

Ownership

In Roman religion, Terminus was the god who protected boundary markers. His name was the Latin word for Marker. Terminus guarded the limit of the field and watched over it. A neighbor dared not approach too near it: “For then,” says Ovid, “the god who felt himself struck by the ploughshare, or mattock, cried, ‘Stop: this is my field; there is yours’.” To encroach upon the field of a family it was necessary to overturn or displace a boundary mark which was the manifestation of a deity. Equivocating the violation of property with an offense towards the gods illustrated the sacred nature of ownership. In Kuyperian terms – which we will discuss later – the sphere of sovereignty under which the right to land was endowed and protected was that of the gods. The institution of private property held an intrinsic moral value which, if violated, would cause harm in the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-0434-5 / 9798350904345 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 745 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich