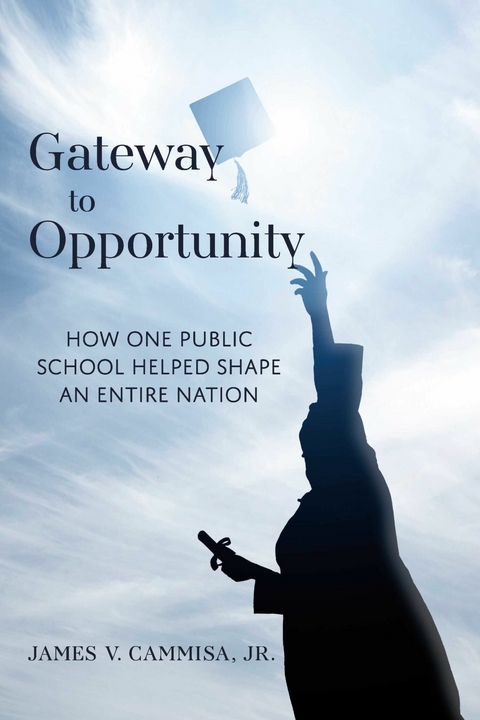

Gateway to Opportunity (eBook)

176 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-4612-5 (ISBN)

Gateway to Opportunity: How One Public School Helped Shape an Entire Nation is like a Who's Who in American history. Its chapters deliver lessons and anecdotes from the storied history of the Boston Latin School-the first American public school in existence for over 385 years-and which produced notable alumni including five signers of the Declaration of Independence, a Nobel laureate, captains of industry, as well as visionaries in the arts and sciences. Most remarkable is the indelible character-building and philanthropic qualities this school infused into each of its graduates. Told from the vantage point of one Latin School alumnus, readers will gain a deep appreciation for this luminous institution that helped in building the American dream.

CHAPTER I:

Building Blocks of the

American Dream

You see things; and you say “Why?”

But I dream things that never were; and I say, “Why not?”

—George Bernard Shaw

The phrase American Dream was not coined by politicians or pundits. Nor was it intended to be a bumper sticker or rallying cry. Rather, it was meant to signify so much more. It was designed to serve as a set of principles upon which all people could flourish. The phrase itself, the American Dream, is credited to an American colonial historian, James Truslow Adams, who in 1931, published a book entitled The Epic of America. His work, ironically written during the Great Depression, dealt with the historical events and issues that he believed would have significant bearing on shaping the American character. Adams, who shared no relation to any U.S. presidents, envisioned a dream that consisted not of material possessions, but rather moral elements. In his book, Adams defined the American Dream as follows:

The American Dream is that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement ... It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and to be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.

Adams’s work was the focus of many other scholars over the decades. In one well-researched book, The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation, Jim Cullen, a writer, and professor of American civilization, explored the multi-faceted dimensions of the Dream. His analysis included the notions of equality and upward mobility and provided a blueprint for forging the American character. Scholars agree that the Dream should not be interpreted as a political, economic, or social doctrine. Rather it should be embraced as a cultural ideal, or aspiration—much like any national ethos or credo, a common set of ideals, attitudes, values, and beliefs which cultural historians agree have influenced the way Americans see themselves and their nation. The Dream has had other connotations as well. Included among these was a sense of possibility, high expectations, and personal fulfillment. It embraced the notion that working hard and doing right would enable anyone to succeed in the land of opportunity. It echoed a “can-do” attitude, characterized by optimism, and hope about a brighter future. Central to this notion was the idea that our children could do even better than we ever could do for ourselves by becoming better educated and taking advantage of living in an upwardly mobile society. Yes, it’s true, our country was blessed with bountiful national opportunities and resources, but it would take the American work ethic, often hard labor and sweat equity, to truly reap its rewards.

Over the years, scholars have used a series of descriptive phrases that lend greater clarity to what the American Dream means, including concepts like freedom, justice, work, education, excellence, frugality, family, and community, to name just a few. Several Calvinist values were also attributed by many scholars: self-reliance, enterprise, hard work, austerity, and one’s obligation to community. Although these may smack of religious tenets, they are believed to also apply to America’s secular culture, even today.

Although the American Dream has become common vernacular, its origins date far back, before it was ever called anything, but rather was a way of life.

Puritan Ideals

The real birth of the American Dream occurred in 1630 alongside John Winthrop’s Massachusetts Bay Company. An English barrister and religious reformer, Winthrop financed a fleet of eleven ships with 700 individuals sailing from England in 1630, ten years following the landing by the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. Winthrop’s settlements were established along the shores of what is now known as Boston Harbor. He would serve as the company’s leader for most of the next twenty years.

The new settlers were not explorers, adventurers, or traders. Rather, they were entire families who chose to separate from the Church of England and form a holy commonwealth of their own. They were in search of a better life in a new land, and thus was born the American Dream.

Hard work would be necessary for this dream to be realized. Geography was not in the Puritans’ favor. Unlike the Jamestown settlement of Virginia, which was the first permanent English settlement in the New World, and which benefited from warm climate and fertile soil, New England soil was of glacial origin and short summers made raising crops difficult. The settlers would have to look to the forests, rivers, and streams as resources from which they could build their colonial economy. Fishing, hunting, and shipbuilding, therefore, quickly became important local industries. Individual entrepreneurs made up a large portion of the workforce—tanners, blacksmiths, masons, wheelwrights, glaziers, and millers. Underlying these occupations was the presence of a strong work ethic. In later years, scholars would connect this ethos back to a building block of the American Dream. The Puritans believed that self-discipline and hard work was their calling—not for a better life in the hereafter, but for here on Earth today.

The Puritans also believed that their new society would be a model for others to follow. Prior to their landing while aboard John Winthrop’s flagship, The Arbella, he gave his famous “City Upon a Hill” sermon that proclaimed, “For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill with the eyes of all people upon us.”

It may come as some surprise, but according to many scholars, it was the religious teachings practiced by the Puritans that contributed most to their ability to build a successful new world society. The Puritans believed in separation of church and state. This, as we know, is one of the foundations of our democracy. The Puritans also believed in egalitarianism, or social equality, which permitted parishioners to participate in religious ceremonies and church matters. The congregation was essential and in striking contrast to the top-down hierarchal structure of the then-prevailing Protestant and Catholic churches they left behind in Europe. The congregation would later become the model for the well-known New England town meeting, where every citizen enjoyed freedom of speech, later cited by Franklin Roosevelt as one of America’s Four Freedoms.

Over the years, there has been a lot of criticism of the Puritans and their beliefs. Yes, in some respects, they have been characterized as fanatical, uncompromising, and stubborn. The Salem Witch Trials in 1692 are cited as an example of their fanaticism. Despite this criticism, what they did leave their descendants was a set of beliefs, values, and standards that were the beginnings of the American Dream.

The Declaration of Independence

As historians have examined and re-examined every word in the Declaration of Independence, what was, and continues to this day, to be at the center of debate is the phrase, “that all men are created equal”; created equal, that is, amongst white men. Equality for women and Blacks continued to be on hold for many more generations, with serious moves for equal rights not beginning until 1848, when social activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the first important women’s conference in Seneca Falls, New York. There, this group drafted a Declaration of Sentiments, which was closely patterned after the Declaration of Independence. It outlined demands for equal rights in marriage, education, religion, employment, and public life. Following this ambitious start, the movement continued, only slowly. It wasn’t until 1920, with the ratification of the nineteenth amendment to the Constitution, that women received the right to vote—144 years after the Declaration of Independence was signed.

For African Americans, the road to equality would also be a long, difficult one, with the first of many existing barriers to equality not removed until eighty-six years after the Declaration of Independence was signed. The Emancipation Proclamation, in a series of two executive orders, was issued in 1862 and 1863, followed by the thirteenth amendment that banned slavery completely; and finally, the fifteenth amendment in 1870. The latter amendment declared that “the rights of citizens to vote could not be denied on account of race, color, or previous conditions of servitude.”

Equality for African Americans would still take a good deal longer, and not gain real momentum until the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. the Board of Education ruling ending school segregation. The Civil Rights movement, as we know it today, really began after a seat in the white section of a Montgomery, Alabama bus was denied to Rosa Parks. Martin Luther King, Jr. was now front and center, and his enormous influence would be felt until his death in 1968 and is still felt to this day. King was able to witness the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, banning discrimination in employment practices and accommodations. Following that, the Voting Rights Act outlawed a variety of discriminatory voting...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Jeffrey Cammisa |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-4612-4 / 1667846124 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-4612-5 / 9781667846125 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 622 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich