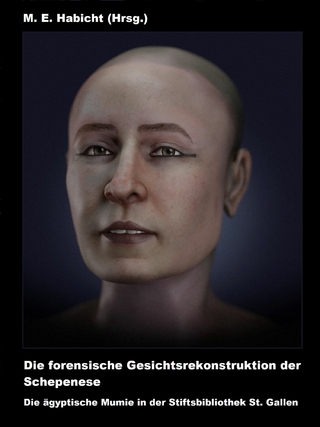

Hollywood's Egyptian Dreams. The Visual Language, Concepts and Costumes in Egyptian Monumental Films (eBook)

209 Seiten

Books on Demand (Verlag)

978-3-7568-3467-9 (ISBN)

Marie Elisabeth Habicht is interested in psychology and culture. She has worked in an advisory and editorial capacity on various book projects. She has published as editor and author, among others: Hollywood's Egyptian Dreams and the electronic edition of the reference book series Under the Seal of the Necropolis.

The Reconstruction of Ancient Music

Film music, also called score or soundtrack, is music composed specifically to accompany a film. It plays a crucial role in setting the mood of a film and can drive the plot (Bullerjahn 2001; Stromen 2005). Already in the silent film era, soundless film was accompanied by music and sometimes by sounds. Both had to be produced live in the beginning. In addition, the rattling of the film projector could be drowned out in this way. Since there was no special film music at first, one fell back on already existing music from operas and the like. In the process, almost standards were established, such as the Wedding March by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy for wedding scenes. Only rarely was the music written individually for a film. The orchestra also soon grew in size. In the beginning, there was often only one pianist playing, then came cinema organs with additional sound effects and even before the First World War, large cinemas used extensive orchestras. With the introduction of sound film, the music was prefabricated along with the film. Composers of film music basically have three composition techniques at their disposal (Pauli 1993):

The leitmotif, known from operas and used especially by Richard Wagner. The leitmotif conveys meaning and has the task of musically representing characters or the plot. The leitmotif can be incorporated into the overall composition or varied.

The underscoring attempts to convey the atmosphere of the events on the screen acoustically and to intensify the visual impressions. Individual cuts of the film are musically doubled in effect. This technique is also called Mickey-Mousing because it is particularly common in cartoons. Because it only works well in comics, underscoring is otherwise rather rare.

The mood technique also conveys a certain atmosphere and underpins the film with music that conveys a certain mood. The same film scene with different music can arouse completely different expectations in the audience. The music really colours the film. The music can also be used as a counterpoint and then blatantly contradicts the image content. This can create an alienation effect.

Depending on the style of music, a certain historical era is also alluded to. This is exactly where the problems begin with monumental films, which are usually set in a distant past. We have (almost) no musical scores from antiquity: The first sheet music in the modern sense was only introduced in the early Middle Ages from the 9th century onwards to write down church music. Admittedly, there had already been initial attempts in antiquity to record notes in the form of letters for pitch and symbols for tone duration. These very early notations are largely lost to us, as mostly only fragments have survived. The same applies to early film music, whose musical scores were often thrown away after the film was completed and today have to be reconstructed at great expense.

The Seikilos epitaph on a tombstone near Ephesus from the 2nd century AD exceptionally transmits a composition to us in its entirety. The stele is now kept in the Danish National Museum. In 1883, however, the first editor did not even understand that these were notes and remarked that the small signs above the text were incomprehensible. In the meantime, it has been possible to reconstruct this ancient melody together with the text in Greek. The soundtrack is published on Wikipedia.

When composing music for monumental films, composers also have to meet the needs of mainstream audiences and their expectations. Just as the costumes and hairstyles reveal which decade the film is from, the style of the film music quickly reveals which era it is from. The Hungarian composer Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995) made decisive contributions to monumental films. You can recognise his film music after just a few bars. In addition to film music, he also wrote concert pieces. In film music, he took his cue from Wagner and the idea that the music for a film must be its own total work of art (Pasch 2013).

The work is often difficult for the composers, as they were often not involved in the planning and creation of the film, but often had to deliver a score after the film was completed under great time pressure. Rózsa began his career in Hollywood with the score for the film "The Thief of Bagdad" (1940), followed by "The Jungle Book" (1942) and "Sahara" (1943). Other successful compositions followed. He served exotic themes, films with emotional breakdown, American crime films and finally he became the leading expert for historical films. It was in this field that he created his most famous works. Rózsa was hired for the film "Quo Vadis" (1951) as early as 1950, even before the film was finished shooting, and was sent to Rome by the producers to draw inspiration from the original location. Until then, the film industry had set monumental films in antiquity, but the music was not adapted to the foreign era.

Rózsa was faced with the problem that little more had survived of Roman music than the depiction of musical instruments, ancient descriptions and a few archaeological remains. In the repertoire of the Romans there was the wind instrument called the tibia, probably with a sound similar to the oboe, the buccina, a horn that was carried over the shoulder and developed into today's trombone. There was also the tuba, a trumpet-like wind instrument. Other instruments came from the Greek cultural area and it is currently assumed that the Greeks also exerted an important cultural influence on the Romans. There was the syrinx (a pan flute), the aulos (a shawm with a sound similar to the oboe) and the salpinx, a kind of trumpet. In addition, there were stringed instruments that were plucked (kithara and lyre). Stringed instruments were apparently unknown in antiquity. In addition to the Seikilos tombstone, three hymns by Mesomedes from Crete were still known in the 1950s.

Rózsa was able to deduce the early Christian music, since these chorales had passed into the "Ambrosian chant" (4th century AD) and the subsequent "Gregorian chant".

Now Rózsa had to master the musical balancing act between reconstructed music of the past and modern dramaturgy for the film plot. A film score that seemed purely "antique" would in many cases not support the drama of the film and thus run counter to the basic idea of film music. With modern harmonisation, polyphony and the unhistorical use of string music, Rózsa succeeded in creating a film score in Quo Vadis that was to be formative for all subsequent monumental films. Alfred Newman ("The Robe" 1953) and Bernhard Herrmann and Alfred Newman together in "The Egyptian" (1954) immediately adopted Rózsa's style.

Ancient music seems to have been monophonic, but orchestral music is necessary for the monumental film score. In Quo Vadis, Rózsa used two types of music, a dramatic scene music and "original music" assembled from ancient fragments, in which he accompanied the melody with chords, thus deviating slightly from the ancient monophony. In order to make it sound "ancient" nevertheless, he used chords that corresponded to the Greek scales. The hymns of the Christians were sung in unison and without harmonisation, so they are practically authentic.

In order not to deviate too much from antiquity, the unfamiliar counterpoint and triads were avoided. In the orchestra, the brass instruments are preferred. The string instruments are only used to play plucked notes, the melodies are played by woodwind and brass instruments.

For the dramatic scene music, Rózsa adhered to the modern rules of the leitmotif. In the film Quo Vadis, the ancient musical instruments appear as props, but they do not play a note - the music score is played with modern instruments: the Scottish harp Clarsach stands in for Emperor Nero's lyre, Roman military music is played with horns, trumpets and trombones etc.

In the Nero hymn "Oh, blazing fire", to burning Rome, Rózsa used the melody from the song of the Seikilos tombstone, written in the Phrygian key. The Triumphal March of Marcus Vinicius, which perfectly expressed the splendour and pomp of the Roman Empire, is considered a masterpiece. The march "Heil Galba" was played only by wind and percussion instruments and formed the bridge to Rózsa's later masterpiece: the film music of Ben Hur. With almost two and a half hours of film score, Ben Hur is not only magnificent, but also one of the longest film scores ever. The leitmotifs of the Roman music contrast with the melodious Jewish music. This is followed by the scores for the monumental films King of Kings (1961) and Sodom and Gomorrah (1962).

In the following years, other composers then took over the monumental film score. The typical Rózsa music influenced various monumental film types (Bible films as well as medieval epics) but not the monumental films set in Egypt: The 10 Commandments of 1956 was musically scored by Elmer Bernstein, who took the romantic musical style of Richard Wagner as a basis. Therefore, one also feels reminded of a dramatic opera. Violins and other modern instruments are recognisable even to musical laymen. Alex North was subsequently also to write the music for "Spartacus" (1961) and "Cleopatra" (1963), and Dimitri Tiomkin was to provide musical accompaniment for "The Fall of the Roman Empire" (1964). They take different paths in style.

Alternative music scores show how much the film score influences the audience's perception.

The entrance of Cleopatra in the original score:

Cleopatra (1963 ) Elizabeth Taylor Entrance into Rome Scene (HD)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vB5Wv8IHVf0

There is a new setting of the famous entry of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.1.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Archäologie |

| ISBN-10 | 3-7568-3467-0 / 3756834670 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-7568-3467-9 / 9783756834679 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 22,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich