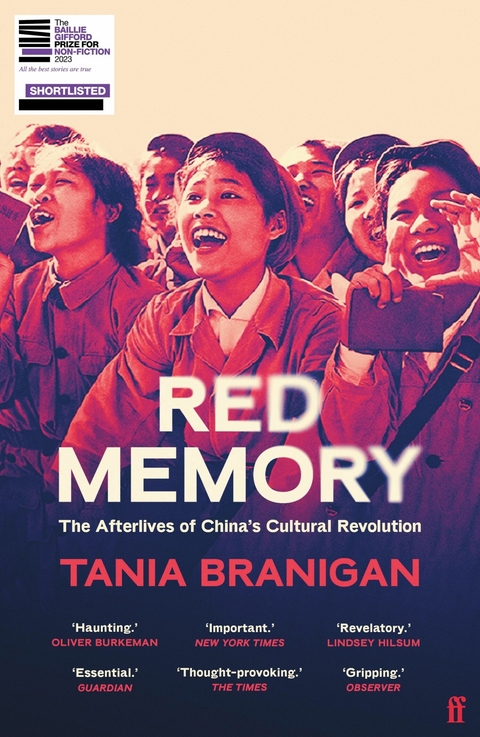

Red Memory (eBook)

320 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-1-78335-267-8 (ISBN)

Tania Branigan is the Guardian foreign leader writer; she spent seven years as the Guardian's China correspondent. Her writing has also appeared in the Washington Post and the Australian. Red Memory is her first book.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION 2023WINNER OF THE CUNDILL HISTORY PRIZE 2023SHORTLISTED FOR THE BRITISH ACADEMY PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION 2023A SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE YEARA BBC RADIO 4 BOOK OF THE WEEKAn indelible exploration of the Cultural Revolution and how it shapes China today, Red Memory uncovers forty years of silence through the rarely heard stories of individuals who lived through Mao's decade of madness. 'Very good and very instructive.' MARGARET ATWOOD'Written with an almost painful beauty.' JONATHAN FREEDLAND'Took my breath away.' BARBARA DEMICK'Haunting.' OLIVER BURKEMAN'A masterpiece.' JULIA LOVELLA 13-year-old Red Guard revels in the great adventure, and struggles with her doubts. A silenced composer, facing death, determines to capture the turmoil. An idealistic student becomes the 'corpse master' . . . More than fifty years on, the Cultural Revolution's scar runs through the heart of Chinese society, and through the souls of its citizens. Stationed in Beijing for the Guardian, Tania Branigan came to realise that this brutal and turbulent decade continues to propel and shape China to this day. Yet official suppression and personal trauma have conspired in national amnesia: it exists, for the most part, as an absence. Red Memory explores the stories of those who are driven to confront the era, fearing or yearning its return. What happens to a society when you can no longer trust those closest to you? What happens to the present when the past is buried, exploited or redrawn? And how do you live with yourself when the worst is over?

These two matters are not finished, and their legacy must be handed down to the next generation. How to do this? If not in peace, then in turmoil …

Mao Zedong, in his last months, on the Cultural Revolution and forcing the Kuomintang to retreat to Taiwan

Ice sealed the lakes at the heart of the city and colour had leached from the streets and skies, smog dissolving into cloud: the horizon was just a memory. The ginkgos in the park were ink tracings now. Pet dogs wore thick jumpers this morning, and had scuttered past with a stony resolve I recognised. Though I was indoors again, still swathed in layer on layer of wool, the cold continued to insinuate itself. Soon it was bone-deep. These industrial buildings to the north of Beijing, once used to manufacture armaments, were beloved by artists for their bare concrete walls, lofty ceilings and expanses of glass, all of which contributed to the studio’s mortuary chill.

I’d heard that the paintings were large, but that hadn’t prepared me. Each was two and a half metres high and, hung on the walls, dwarfed me further, so that I was the one under scrutiny. At this scale, and monochrome, even smiles were somehow sombre. On first sight, the images were almost photographic. These faces had the same fated quality as pictures of missing children, as if they too anticipated what I knew awaited them. Step closer and the clear lines scattered into a flurry of brushstrokes; smeary blotches and swipes of ash and charcoal. The pictures both dominated and eluded. The paint was thick, encrusted on the canvas and stuck here and there with bristles. I stepped back again and recognised some of the faces inspecting me. A celebrated author, behind heavy glasses. A glowering actress. Communist heroes. Others were unfamiliar. Famous, infamous or unknown, all were painted in precisely the same way, at the same immense scale. There was tragedy here, and villainy too, but the painter drew no distinctions: ‘Even if they are bad people, they are still people,’ he said.

He was an unassuming man, bundled in a fat black vinyl jacket and marmalade-coloured sweater – an outfit a student half his age might have worn, but which he carried off easily. He drew on cotton gloves to hunt through the stacks for the canvas I’d requested, then pulled out a frame and bore it to an easel before untaping the cover. A face emerged, unyielding, though with a trace of a smile: benign? Triumphant? Chairman Mao gazed out, and I gazed upon him. I was used to him in grand dimensions, from the giant portrait that still hung on Tiananmen, the great red gate in the capital’s heart. It was startling that the others matched him as I looked around. There were over a hundred pictures in all, but one was missing, Xu Weixin told me: the very first portrait he had drawn, as a child. He had grown up in China’s far north-west. He had liked his gentle teacher, Miss Liu, so was shocked and shamed when it all erupted and he learned of his naivety – she was, they warned him, a class enemy: the daughter of a landlord. Outraged at the discovery, he steeled his heart and did the right thing, used his pen, pinned the hideous caricature to the blackboard, and still remembered, as if it were this morning, the moment she walked in and saw it, and how the blood drained from her face. She understood already what it might mean, what might follow. He was too young, but grew up fast. Soon he would see them burning pictures and breaking Buddhas, beating people with sticks and metal bars. He would hear the screams, and listen to the silences that followed.

He didn’t dwell upon his tale, though his memories were ‘very, very vivid’; he outlined it efficiently. ‘You were eight …’ I began. I was only checking the details, but he took it for a different kind of question, about his culpability, or perhaps a reassurance he hadn’t wanted.

‘Of course, I was responsible. It’s only a question of how big or small my responsibility was.’

Big enough that, all this time later, he’d devoted five years to these giants, spending days on his ladder to define a hairline, shape a brow. Each of Xu’s subjects had played a part in this madness, as victim or perpetrator; often both. Some of them had whipped up rage and hatred. Others had died in the struggles. Painting them helped him take responsibility, he said; they were tied to that first picture, for which he still felt guilty, but which had helped him to understand how people could turn upon each other. He thought that others, seeing his work, might begin to understand too.

Modern China had bred outspoken artists, fond of provocative statements – giving the finger in Tiananmen Square; sculpting Mao riding bareback on a pig. Xu was not interested in provocation, or statements. He didn’t satirise forced demolitions, boast of eating foetuses or simulate sex. He held a good position at one of China’s most prestigious universities. His very medium, oil painting, was conservative. Even once I’d heard about his childhood, his commitment to the portraits was surprising – almost peculiar. He hoped that one day they could hang in a museum, confronting browsers who might, perhaps, be forced into reflection, and in facing their past help their nation to move forward. But the difficulties of his project were encompassed by its title, the careful Chinese Historical Figures with its telltale addendum, 1966–76. Those were the dates of the Cultural Revolution: the decade of Maoist fanaticism which saw as many as 2 million killed for their supposed political sins, and another 36 million hounded. They were guilty of thoughtcrimes: criticism of Mao or the Party or its policies, or remarks that might be interpreted that way. Others, like Xu’s teacher, were guilty by blood, their parentage enough to condemn them. The hysteria, violence and misery had forged modern China, but the movement was rarely mentioned these days. It was not utterly taboo, like the bloody crackdown on Tiananmen Square’s pro-democracy protests in 1989. In the past it had been discussed more widely, although never freely. But by the time I arrived in 2008 it dwelled at the margins, biding in the shadows. Fear, guilt and official suppression had relegated it to the fringes of family histories and the dustiest shelves of records.

Xu had been able to show the pictures together just once, in Beijing, a few years before – ‘a ghostly experience,’ recalled Carol Chow, the daughter of one of the subjects. She had stood face to face with the father she could not remember, the father who had died in the tumult, now painted like a memory, as though he were frozen in time. After all I had heard, I wanted to see him too. Xu brought out the picture at my request: I saw a handsome young man in a fur-trimmed jacket, with quizzical eyes and the hint of a smile upon his confident face – too confident, perhaps. Zhou Ximeng came from a long line of distinguished scholars and himself excelled at every stage, topping the class throughout his studies. For centuries, education had been the key to social advancement in China. In the Cultural Revolution it could mean ruin. To stand out was not an advantage.1 A mob of Red Guards, Mao’s youthful political vigilantes, seized him for a passing comment, holding him prisoner in a village not far from Beijing. He was twenty-seven, recently married and newly a father, but his daughter believed he had reached a point where his life seemed beyond his control. ‘You had to first renounce yourself, and then renounce your family and friends. I think, when he got to that point, really, he just closed up.’

Chow, then just a few months old, would never see him again. Her father would briefly escape his captors, to throw himself in front of a train. Three decades later his mother would kill herself too. The night before, the family heard her call out in her sleep: ‘Ximeng, Mummy’s coming –’

It was Chow’s story that brought me to Xu’s studio. I had heard it from her husband, an investor and astute political observer; we’d met for lunch at an Italian bistro, where we ate grilled sandwiches, swapped gossip and picked over recent developments in Beijing. Then, over coffee, he mentioned a trip that the couple had made a few years before, to the village where Chow’s father had been held. The farmers had been kind enough when the family returned. They still remembered the young man from all those years ago. They recalled how quiet he had been that morning. They spoke of recovering his body from the tracks, and burying it close by. But they dismissed the family’s quest to reclaim him – struggled to even comprehend it. Too many bones from those days lay jumbled in the soil. How did anyone expect them to know which one of the bodies was his?

It was a cruel tale, but not the worst I had heard from the era. Perhaps that was why it haunted me. I knew that the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, which ended only after Mao Zedong’s death, were savage, unrelenting and extraordinarily destructive. The violence and hatred terrorised the nation, annihilated much of its culture and killed key leaders and thinkers. The movement was an emperor’s ruthless assertion of power, which Mao directed and set in motion to destroy opposition within the Party. But it was also an ideological crusade – a drive to reshape...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.1.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Sammeln / Sammlerkataloge |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Cultural Revolution, Chinese politics, Xi Jinping • Lea Ypi, Wild Swans, Nothing to Envy, Stasiland • Mao Zedong • Svetlana Alexievich, Gary Younge, Empire of Pain • Travellers in the Third Reich |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78335-267-1 / 1783352671 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78335-267-8 / 9781783352678 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 402 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich