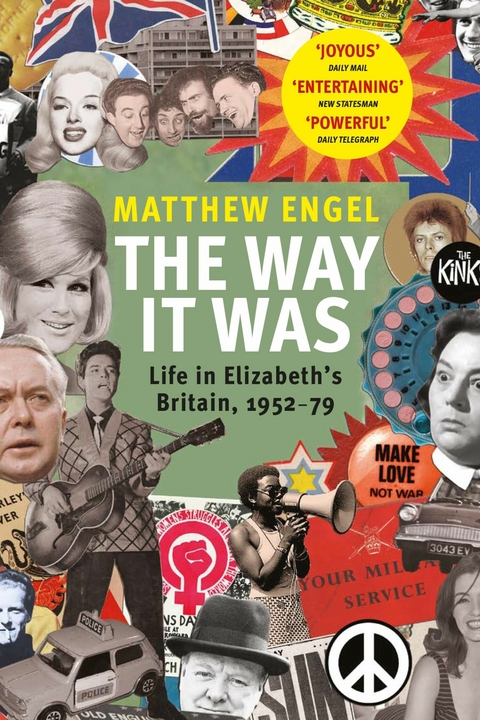

Way It Was (eBook)

640 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-78649-668-3 (ISBN)

Matthew Engel is a journalist and author. He has written for the Guardian and Financial Times, among other publications, and was the editor of the Wisden Cricketers' Almanack for twelve years. His books include Eleven Minutes Late and Engel's England.

She came to the throne in 1952 when Britain had a far-flung empire, sweets were rationed, mums stayed home and kids played on bombsites. Seventy years on, everything has changed utterly - except the Queen herself, ageing far more gracefully than the fractious nation over which she so lightly presides. How did we get from there to here in a single reign? To cancel culture, anti-vaxxers and Twitter feeds? Matthew Engel tells the story - starting with the years from Churchill to Thatcher - with his own light touch and a wealth of fascinating, forgotten, often funny detail.

Matthew Engel is a journalist and author. He has written for the Guardian and Financial Times, among other publications, and was the editor of the Wisden Cricketers' Almanack for twelve years. His books include Eleven Minutes Late and Engel's England.

1

WIVES AND SERVANTS

ON NEW YEAR’S DAY 1960, A YOUNG MAN CALLED JOHN ‘HOPPY’ Hopkins arrived in London to make a new start. He was 22 and a graduate of Cambridge, where he had studied general science, jazz, drugs and sex, not necessarily in that order. For a while, he worked as a technician for the Atomic Energy Authority at Harwell before taking a holiday at a Communist youth festival and, not surprisingly, losing his security clearance.

He brought his camera and soon found a job as an assistant to a commercial photographer. ‘It was heaven,’ he said. He also found himself welcome in the scattered pockets of louche subversiveness that were starting to emerge in the run-down areas of West London.

Photographers had little status in the 1950s. At a function, one dared to approach Betty Kenward, the absurd figure whose ‘Jennifer’s Diary’ column in Tatler (and then Queen) fawningly chronicled upper-crust social life. ‘My photographers never speak to me at parties,’ she snapped imperiously. In February 1960 this upstart, Jones or something, became engaged to Princess Margaret. In the springtime they were married in Westminster Abbey amid full palaver, complete with Richard Dimbleby TV commentary, and Antony Armstrong-Jones went on to become Earl of Snowdon.*

The marriage, by chance, resembled a medieval dynastic alliance. It linked the royal family with Bohemia, or at least the London versions of it like Fitzrovia, Notting Hillia (now up-and-coming) and Rotherhithia, where Armstrong-Jones rented his bachelor flat.

And thus indirectly with John Hopkins. Photographers were about to join the elite. Snowdon was to be closely associated with the pioneering Sunday Times magazine, launched in 1962; Hopkins took much-admired photos of the rock scene and the capital’s underbelly. He also became a major figure in what would become aggrandized as Britain’s counterculture, and for a while was what the music producer Joe Boyd called ‘the closest thing the movement ever had to a leader’.

That was about five years away, which was a long, long time in the 1960s. There is still endless debate about when the sixties, as a concept, began. Any date between 1956 and 1963 might be defensible. But 1 January 1960, and Hoppy’s arrival, is at least one possibility.

The counterculture as such comprised a tiny fraction of the population. For many millions of Britons – Kenward on the one hand, Tyneside shipworkers on the other – the events were not much more than a rumour. But it was a revolutionary time, when new sensations came so frequently that the world seemed to be spiralling out of control. And it was also a war, a cultural war, between the attitudes of old and new. And though, by the end of the decade, the new had captured once-unimaginable terrain, not every victory would be permanent, not every victory could be justified, not every victory was cheered by those one might think would be cheering it.

The News of the World – ‘the Screws’ – was a British institution that had changed not at all over the previous decade, except that – like its chief rival for the nation’s attention on a Sunday morning, the church – its audience had been drifting slowly downwards: from a staggering sale of 8.5 million in 1950 to a mere 6.5 million.*

Its discreetly Delphic messages about the week’s more lubricious court cases still reached far more than those of its godly opposition. But its owners, the Carr family, were getting nervous, and on the last day of the decade it was announced that Stafford Somerfield was taking over as editor. He had an agenda, was given a budget to fulfil it, and immediately paid £35,000 for a series of ghostwritten articles under the byline of the sexy actress Diana Dors, whose semi-private life was more daring than her film roles.

And over the opening weeks of the 1960s, she delivered what Somerfield wanted: ‘There were no half measures at my parties. Off came the sweaters, bras and panties. In fact it was a case of off with everything – except the lights . . .’ This was the first, if not the most typical, example of the new brazenness. And circulation did perk up for a while.

Before Dors had even removed her coat in print, never mind her panties, there came more portentous news. Penguin Books had decided to publish an unexpurgated paperback of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the D. H. Lawrence novel that had lain, officially unpublished in Britain, for more than thirty years. Penguin’s founder, Sir Allen Lane, was emboldened by a court overturning its prohibition in the US – and even more by the 1.5 million copies sold as a result. Lawrence’s explicit depictions of the affair between Lady Constance Chatterley and her husband’s gamekeeper, and the even more explicit language used in the process, was set up to be the first test case for the new, more flexible Obscene Publications Act.

Though it turned out not to be quite the first. Frederick Shaw, reinventing a tradition that dated back to Charles II’s day, published a book – the Ladies’ Directory – giving contact details for London prostitutes, a useful service for potential customers since touting for business had been taken away from public view under another 1959 law, the Street Offences Act. The courts did not think it useful, however. Shaw got nine months for ‘conspiracy to corrupt public morals’, and henceforth the ladies concerned were obliged to post coded messages in newsagents’ windows: FRENCH LESSONS GIVEN OR LARGE CHEST FOR SALE. Later they would slip cards into phone boxes. Love does not always find a way, as Princess Margaret had discovered some years earlier, but sex does.

The Chatterley case came to trial in October 1960. In folklore it was lost the moment the prosecution counsel, Mervyn Griffith-Jones, asked the jury – twelve property-owning but otherwise fairly random Londoners – in his opening speech to consider: ‘Would you approve of your young sons, young daughters – because girls can read as well as boys – reading this book? Is it a book that you would have lying around in your own house? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?’ And several onlookers noticed the jurors suppress titters at that moment. Griffith-Jones also reminded them that phallus meant penis, ‘for those of you who have forgotten your Greek’.

The case may have been lost even before that. The defence called thirty-five expert witnesses to assert the book’s literary value, with more in reserve; the prosecution had none. This was not a cunning plan or arrogance or even a technical legal decision, as the government claimed at the time; the Home Office could not find a single reputable figure to speak against Lady C. Some observers felt Griffith-Jones had not properly read the book, though he had painstakingly counted the thirty uses of fuck or fucking, the fourteen cunts and so on, down to the three pisses. All the witnesses had read it, even though the book was banned.

Yet Griffith-Jones had reason to be confident. The judge, Mr Justice Byrne, had been carefully chosen. He was 64, sitting for the final time, a conservative Catholic with close government connections, and in his summing-up he did his best to help. Weirdly, his wife sat beside him every day, and if the judge’s face was not expressive enough during the trial, hers was. And after the ‘not guilty’ verdict came in, he omitted the customary thank-you to the jurors and just glared at them.

Eight days later, on 10 November, Lady C was legally sold in Britain at last. Penguin did not match the sales of the much bigger American market, it surpassed them, reaching 2 million in the seven weeks remaining of 1960. The judge harrumphed into retirement, but Griffith-Jones lived to fight more wrong-headed battles on behalf of the state, one of which would have tragic consequences.

Most opinion appeared to back the judgment. The right-wing Daily Express, the left-wing Daily Herald and the Methodist preacher Donald Soper all gave nuanced approval. And The Guardian* marked the occasion by printing, in a quote from the trial, the word fuck, believed to be a British-newspaper first (rogue insertions by mischievous printers excepted). One Tory MP called for the paper to be prosecuted for obscene libel.

About the book, some peers were even more hysterical. The 6th Earl of Craven was travelling north on the M1 on publication day and stopped at the newly opened Newport Pagnell service station. He later told the House of Lords what he saw: ‘At every serving counter sat a snigger of youths. Every one of them had a copy of this book held up to his face with one hand while he forked nourishment into his open mouth with the other. They held the seeds of suggestive lust.’

The earl was quite a young fogey: he was 43 at the time. It apparently never occurred to him that if the case had not been brought, and Lady C had been published normally, it would have sold well without making much impact on sniggers of youths. Not every peer was that daft. One of them was asked if he minded his daughter reading the book. Certainly not, he said, but he had the strongest objection to it being read by his gamekeeper.

Mostly, 1960 did a remarkably accurate impersonation of the 1950s, as would 1961 and 1962....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.10.2022 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 3x8pp b&w plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Zeitgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | andrew marr • Bill Bryson • books of the year • books on the queen • British history • Charles • David Kynaston • Dominic Sandbrook • Elizabeth II • History of britain • Jeremy Paxman • Jubilee • king charles iii • Monarchy • Philip • platinum jubilee • Prince of Wales • Queen • Social History • Thatcher • The Crown • waterstones best book • Winston Churchill • wwi |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78649-668-2 / 1786496682 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78649-668-3 / 9781786496683 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 17,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich