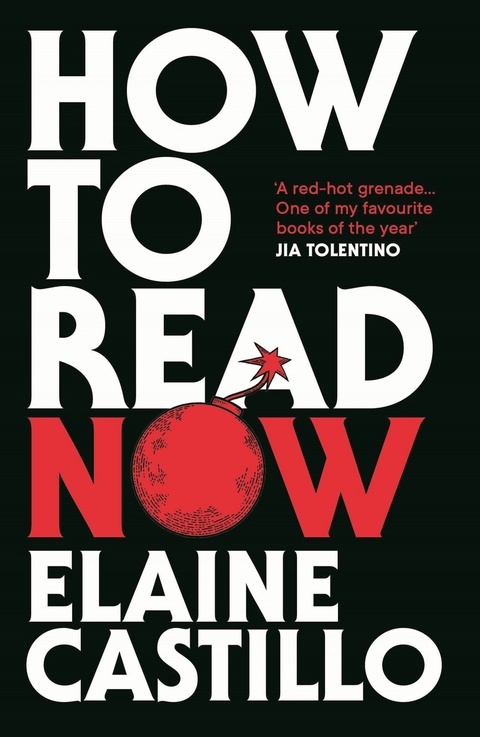

How to Read Now (eBook)

352 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-494-9 (ISBN)

Named one of '30 of the planet's most exciting young people' by the Financial Times, Elaine Castillo was born and raised in the Bay Area. Her debut novel America Is Not the Heart was named one of the best books of 2018 by NPR, San Francisco Chronicle, The New York Public Library, The New York Post, The Boston Globe, Real Simple, Lit Hub, and has been nominated for the Elle Award, the Center for Fiction Prize, the Aspen Words Prize, the Northern California Independent Booksellers Book Award, and the California Book Award.

Named one of '30 of the planet's most exciting young people' by the Financial Times, Elaine Castillo was born and raised in the Bay Area. Her debut novel America Is Not the Heart was named one of the best books of 2018 by NPR, San Francisco Chronicle, The New York Public Library, The New York Post, The Boston Globe, Real Simple, Lit Hub, and has been nominated for the Elle Award, the Center for Fiction Prize, the Aspen Words Prize, the Northern California Independent Booksellers Book Award, and the California Book Award.

AUTHOR’S NOTE,

OR A VIRGO

CLARIFIES THINGS

In the years since my debut novel came out, I’ve been thinking a lot about how to read. Not about how to write—I wouldn’t trust a book about how to write by a debut novelist, any more than I would trust a book about how to swim by someone who’d accomplished the exceptional achievement of not having drowned, once. But reading? Most days when I look back at my childhood, it feels like first I became a reader; then I became a person. And in the postdebut years of touring, and traveling—in hotel rooms in Auckland and East Lansing, on festival stages in Manila and Rome, in bookstores in London, and in the renovated community library of my hometown, Milpitas—a thought came back to me, again and again; a ghost with unfinished business, a song I couldn’t get out of my head: we need to change how we read.

The we I’m talking about here is generally American, since that’s the particular cosmic sports team I’ve found myself on, through the mysteries of fate and colonial genocide—but in truth, it’s a more capacious we than that, too. A we of the reading world, perhaps. By readers I don’t just mean the literate, a community I don’t particularly issue from myself, although I am, in spite of everything, among its fiercest spear-bearers. I mean something more expansive and yet more humble: the we that is in the world, and thinks about it, and then lives in it. That’s the kind of reader I am, and love—and that’s the reading practice I’m most interested in, and most alive to myself.

The second thought that has come to my house and still won’t grab its coat and leave is this: the way we read now is simply not good enough, and it is failing not only our writers—especially, but not limited to, our most marginalized writers—but failing our readers, which is to say, ourselves.

When I talk about reading, I don’t just mean books, though of course as a writer, books remain kin to me in ways that other art forms—even ones I may have come to love with an easier enthusiasm, in recent years—aren’t. At heart, reading has never just been the province of books, or the literate. Reading doesn’t bring us to books; or at least, that’s not the trajectory that really matters. Sure, some of us are made readers—usually because of the gift (and privilege) of a literate parent, a friendly librarian, a caring kindergarten teacher—and as readers, we then come to discover the world of books. But the point of reading is not to fetishize books, however alluring they might look on an Instagram flat lay. Books, as world-encompassing as they are, aren’t the destination; they’re a waypoint. Reading doesn’t bring us to books—books bring us to reading. They’re one of the places we go to help us to become readers in the world. I know that growing up, film and TV were as important to my formation as a critical thinker—to the ways in which I engaged with “representation” in any real sense—so I can’t imagine not writing about them, even in a book supposedly about reading.

When I talk about how to read now, I’m not just talking about how to read books now; I’m talking about how to read our world now. How to read films, TV shows, our history, each other. How to dismantle the forms of interpretation we’ve inherited; how those ways of interpreting are everywhere and unseen. How to understand that it’s meaningful when Wes Anderson’s characters throw Filipinx bodies off an onscreen boat like they’re nothing; how to understand that bearing witness to that scene means nothing if we can’t read it—if we don’t have the tools to understand its context, meaning, and effect in the world. That it’s meaningful to have seen HBO’s Watchmen and been moved and challenged by its subversive reckoning with the kinds of superhero tropes many kids, including myself, grew up on. Books will always have a certain historical pride of place in my life—but it’s also because of books that reading can have a more expansive meaning in that life, both practically and politically.

In a more personal sense, as a first-generation American from a working-class / fragilely middle-class upbringing, most of the people in my life simply don’t read: aren’t sufficiently confident in their English, or don’t have the leisure time, or have long found books and reading culture intimidating and foreclosed to them (for all my love of independent bookstores, I’ve also been glared at like a potential shoplifter in enough of the white-owned ones to temper that love). I don’t want a book called How to Read Now to speak only to the type of people who read books and attend literary festivals—and in the same vein, I don’t want it to let off the hook people who think they don’t read at all. I can’t write a book about reading that tells people there’s only one type of reading that counts—but equally, just because you don’t read books at all doesn’t mean you’re not reading, or being read in the world. Of course, How to Read Now runs off the tongue a little easier than How to Dismantle Your Entire Critical Apparatus.

I’ve been an inveterate reader all my life, and yet I’m writing this book at the time in my life when I have the least faith I’ve ever had in books, or indeed reading culture in general. (The fact that this sentiment coincides with having become a published author doesn’t escape me.) For my sins, I haven’t lost faith in the capacity of books to save us, remake us, take us by the scruff and show us who we were, who we are, and who we might become; that conviction has been unkillable in me for too long. But I have in some crucial way lost my faith in our capacity to truly be commensurate to the work that reading asks of us; in our ability to make our reading culture live up to the world we’re reading in—and for.

When I first began writing this book, I was in Aotearoa, also known as New Zealand, as a guest at the Auckland Writers Festival. Much happened in between those stolen, heady moments of writing on hotel room couches in the spring of 2019 and the (not quite) postpandemic world we now find ourselves in—worrying about the nurses in my family still working on the front lines; supporting loved ones who’d lost their jobs; mourning loved ones who’d lost their lives; joining the many marches here in the Bay to protest the anti-Black police brutality that took the lives of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, among so many others, as well as the rise in anti-Asian hate, fueled by Trump’s virulently racist coronavirus rhetoric. I’d also rolled into lockdown after already being essentially confined at home in convalescence for over two months: in December 2019, just before Christmas, I’d been hospitalized for emergency surgery due to the internal hemorrhaging caused by an ectopic pregnancy, in which my left fallopian tube was surgically removed in a unilateral salpingectomy. This was my second pregnancy loss, after complications with a D&C for a miscarriage at twelve weeks left me in and out of King’s College Hospital over the summer of 2017, back when I was still living in London and editing my first novel, America Is Not the Heart.

All this to say, when I look back at the inception of this book, I can’t help but feel that I’m looking at it from an entirely different world. In 2018 and 2019, the things I’d witnessed and experienced in the publishing industry during those early first-novel book tours and festivals made it distressingly clear to me that there was also something profoundly wrong with our reading culture, and particularly the ways in which writers of color were expected to exist in it: the roles they were meant to play, the audiences they were meant to educate and console, the problems their books were meant to solve. It started to feel like it would be impossible to continue working in this industry if I didn’t somehow put down in writing the deep-seated unease I had around this framing.

I wanted to write about the reading culture I was seeing: the way it instrumentalized the books of writers of color to do the work that white readers should have always been doing themselves; the way our reading culture pats itself on the back for producing “important” and “relevant” stories that often ultimately reduce communities of color to their most traumatic episodes, thus creating a dynamic in which predominantly white American readers expect books by writers of color to “teach” them specific lessons—about historical trauma, farflung wars, their own sins—while the work of predominantly white writers gets to float, palely, in the culture, unnamed, unmarked, universal as oxygen. None of these are particularly new issues; Toni Morrison’s landmark, indispensable Playing in the Dark remains the urtext on the insidious racial backbone of our reading culture. But I was occasionally alarmed during book tour events when I would make reference to Playing in the Dark, and realize that many in the audience had not read it and, indeed, seemingly hadn’t ever had a substantial reckoning with the politics, especially racial politics, of their reading practices.

That was then. I still believe in reading, and I still very...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.8.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | america is not the heart • ART • BBC Radio 2 Book Club • bestselling nonfiction 2022 • Critical theory • Criticism • Culture • Diversity • Essays • how to read • jia tolentino • Joan Didion • Manifesto • melissa febos • Politics • Rachel Kushner • racism in reading • Reading • rebecca solnit • Samantha Irby • Toni Morrison |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-494-5 / 1838954945 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-494-9 / 9781838954949 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 792 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich