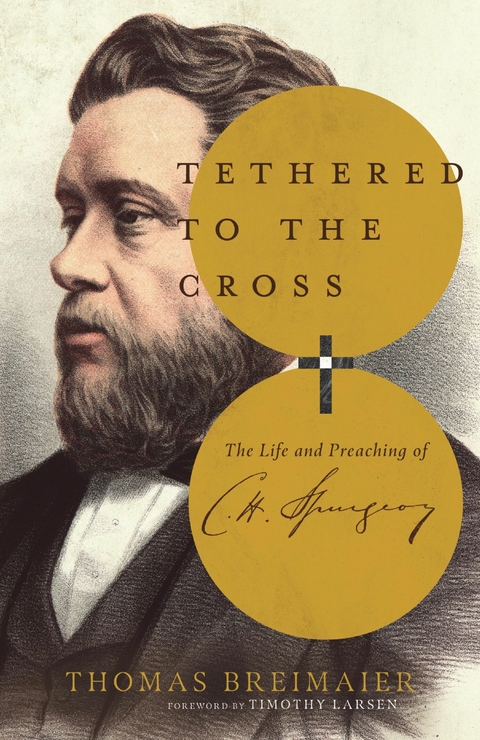

Tethered to the Cross (eBook)

288 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-0-8308-5331-1 (ISBN)

Thomas Breimaier (PhD, University of Edinburgh) lectures in systematic theology and history at Spurgeon's College in London. Originally from Cleveland, Ohio, he holds degrees from Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College Graduate School and is a book review editor for the Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology.

Thomas Breimaier (PhD, University of Edinburgh) lectures in systematic theology and history at Spurgeon's College in London. Originally from Cleveland, Ohio, he holds degrees from Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College Graduate School and is a book review editor for the Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology.

FOREWORD

Timothy Larsen

A TRULY GREAT PREACHER IS MARKED by a combination of faith and fire—faith in two senses. The first is the faith was once delivered unto the saints. The sermons of great preachers are messages of substance. They are not merely frothy concoctions of sentiment and anecdote, but rather they find their center of gravity in the purity of doctrine, in the profundity of Scripture, and in the power of the gospel. The second is faith in the sense of personal conviction. This living faith is also fuel for the fire. Great preachers have convictions that are contagious. They speak existentially to the whole person, unleashing deep emotions and galvanizing the heart, the intellect, and the will. They move their hearers, and not merely in an ephemeral and superficial way. Deep calleth unto deep. The hearer feels located, as if the preacher is speaking specifically to him or to her. The messenger provokes a response in the listener.

In the context of specific ages, nations, or denominations, a few figures will emerge preeminent, widely hailed as fitting the above portrait of a great preacher. In the early church, John Chrysostom was one. His very name, Chrysostom (the golden-mouthed), was really an honorary title in tribute to his power in the pulpit. In the twelfth century, I would not have wanted to try to hold out with a bad conscience against an authoritative proclamation from Bernard of Clairvaux—nor in the fourteenth century against a piercing oration from Catherine of Siena. In the eighteenth century, even a penny-pinching Deist such as Benjamin Franklin found himself throwing all his money into the offering plate when George Whitefield made the appeal. Would that Franklin had also joined the myriads who gave their lives to Christ when Whitefield delivered a sermon! The nineteenth century was a sermonic age that produced a company of great preachers. Even just in the single city of London many worthy voices were raised in the cause of Christ whose ministries resounded to other countries and down the decades well beyond their deaths. I have been a Victorian scholar my whole career, but if I was transported back in time to Victorian London, I would skip the chance to see Queen Victoria and opt instead to go hear Catherine Booth, the mother of the Salvation Army, preach with fiery conviction the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Greatest, of course, is a silly category. The kingdom of God is not a listicle. When Stanley Hauerwas was named “America’s Best Theologian” by Time magazine, he had the grace and wisdom to reply, “Best is not a theological category.” We make no more invidious a claim than that Charles Haddon Spurgeon is numbered among the great preachers. And Spurgeon himself, desiring no solitary perch of preeminence, would have been the first to add, “And may their tribe increase.” Every great preacher from the past whose words we can read or whom we can learn about is a gift to us today. We do not need to choose. They are a great cloud of witnesses, and they all belong to us. The memory of the righteous is a blessing.

Still, Spurgeon’s ministry was so extraordinary according to so many metrics that authors shy away from making the superlative claims that stare them in the face. No one I have read has ever said that Spurgeon, in his day, was the pastor of the largest Christian congregation in the entire world. If he was not, however, who was? If he was not the Christian author with more words in print than any other, then who was? If his sermons did not circulate more widely than anyone else’s, then whose did? If he was not the most popular preacher of the nineteenth century, then who was? Again, these claims do not matter in themselves. They are, in truth, as we have already intimated, a little unseemly when discussing servants of Jesus Christ. The point is simply that it was so incalculably vast that it is easier to underestimate than overestimate the reach and significance of Spurgeon’s ministry.

You could be buried alive in books about Spurgeon. His giant reputation has created an entire publishing phenomenon focusing on just one man. The first book about Spurgeon was published when he was just twenty-two years old! By the time he was twenty-three, the first full biography had already appeared. At his death at the early age of fifty-seven, biographies of Spurgeon started appearing at the rate of one per month. Just one of these, The Life and Work of Charles Haddon Spurgeon by G. Holden Pike, was six volumes long.

Still, Spurgeon has been scandalously neglected by scholars. It is hard to think of anyone with his level of fame and reputation who has been so thoroughly ignored. There are literally only a handful of scholarly books on Spurgeon. For a long, long time, Patricia Kruppa’s Charles Haddon Spurgeon: A Preacher’s Progress, published in 1982 but essentially her 1968 PhD dissertation, held the field alone. It was a flawed study, but as the only scholarly one, it was also essential. (And there is still such a dearth of academic studies on Spurgeon that it has been recently reissued by a new publisher without even being revised or updated.) Today, however, people have the privilege of reading Tom Nettles’s wonderful and worthy book, Living by Revealed Truth: The Life and Pastoral Theology of Charles Haddon Spurgeon (2013). If you want to read a biography of Spurgeon, start with it. Nettles did his research well, but he chose to write a book that tilted toward the preferences of the popular market rather than attending to the needs and concerns of scholars. Perhaps the best academic study of Spurgeon hitherto has been Peter J. Morden, “Communion with Christ and His People”: The Spirituality of C. H. Spurgeon (2010).

Thomas Breimaier’s Tethered to the Cross: The Life and Preaching of Charles H. Spurgeon is the most important scholarly study of Spurgeon that has ever been written. It is the very best place to start for anyone who wants to study Spurgeon. It is extremely well researched and highly judicious. You can trust that the claims are well grounded and right. It is also a joy to read.

Before turning to the central themes of Tethered to the Cross, it is worth mentioning a few unexpected delights that one encounters along the way—almost by the bye, but not quite. I myself have done research and written scholarly chapters on Spurgeon, and for what it is worth, these were new delights for me that either Breimaier has uncovered or I had somehow hitherto missed. One is Spurgeon’s poignant and profound sermon “Accidents, Not Punishments.” His text was Luke 13:1-5. People were shaken by recent deaths in a train collision, and Spurgeon preached against the assumption that these people were being punished because of their exceptional sinfulness. When David Livingstone died deep in the interior of Africa, they found a copy of that sermon among his possessions. He had marked it “very good.”

I was also struck by Spurgeon’s refusal to take up even seemingly Christian or scriptural concerns that he felt would deflect him from his fundamental task of preaching the gospel. On the issue of a young earth, he simply retorted, “I do not know, and I do not care, much about the question.” Likewise he refused to join the rage among conservative Christians for eschatological theories and end-times speculation. On the imagery in the book of Revelation, Spurgeon declared, “I confess I am not sent to decipher the Apocalyptic symbols, my errant is humbler but equally useful, I am sent to bring souls to Jesus Christ.”

I was also pleased to learn about the amazing Lavinia Bartlett, a woman in Spurgeon’s congregation who matched him in her zeal for souls and in the converting power of her Bible teaching. Spurgeon’s own magazine, The Sword and the Trowel, recommended that male preachers sit under Bartlett’s ministry in order to learn how to be more effective. Stories were told of souls whose hearts had remained hard even under Spurgeon’s ministry but had been cracked open for Christ to enter in through Bartlett’s teaching. Likewise I was riveted by the account of an African American preacher and former slave from Virginia, Thomas L. Johnson, who trained at Spurgeon’s seminary, the Pastors’ College, before going on to a fruitful ministry. Echoing Paul’s letter to Philemon, Spurgeon sent him out into a racist world with this reference: “He is a beloved brother in the Lord and should be received as such.” And I was staggered to learn that there came a point at which the majority of all the Baptist ministers in England and Wales had been trained by Spurgeon in his Pastors’ College. Not only did Spurgeon apparently have the largest congregation in the world, but the second largest congregation in London (and, for all I know, the world) was one founded by his disciple and former student, Archibald Brown—the East End Tabernacle. (After Spurgeon’s death, Brown would eventually succeed Spurgeon at the Metropolitan Tabernacle.)

Whatever you think of Spurgeon—even if you dislike him—if you want to study him, this book is essential for you. If you love Spurgeon, however, you will love this book. Breimaier has gone straight to the secret of Spurgeon’s power. Charles Haddon Spurgeon preached Christ and him crucified. Spurgeon’s aim was not simply to preach the Bible. It was to preach the gospel, through the Scriptures, by the power of the Holy Spirit. The gospel kept his eyes steadfastly fixed upon the cross. With the power of the cross of Christ to convert...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.10.2020 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Timothy Larsen |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Schlagworte | Bible • Biblical Interpretation • Charles H. Spurgeon • charles spurgeon • Charles spurgeon biblical interpretation • Charles spurgeon biography • Charles spurgeon Christology • Charles spurgeon theology • Christ • Christological reading of scripture • Cross • crucified • Hermeneutic • hermeneutics • homiletics • Interpretation • Jesus Christ • Metropolitan Tabernacle • ministry • Preacher • Preaching • prince of preachers • Scripture • Spurgeon • spurgeon preaching • tethered to the cross |

| ISBN-10 | 0-8308-5331-6 / 0830853316 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-8308-5331-1 / 9780830853311 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich