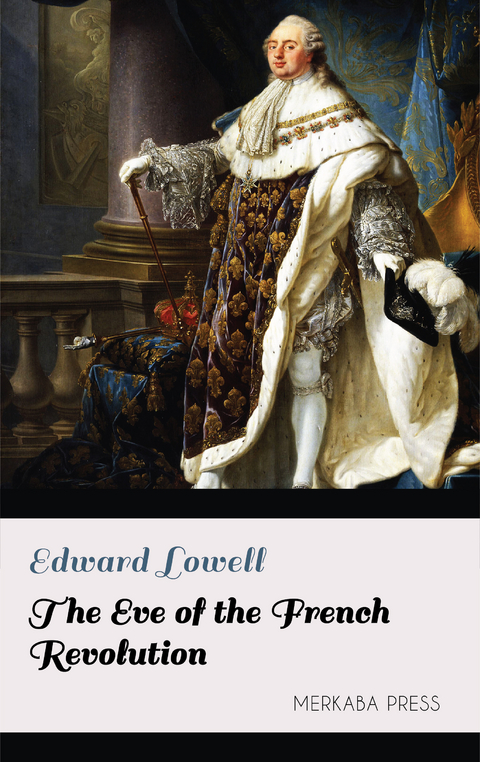

The Eve of the French Revolution (eBook)

193 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-002021-5 (ISBN)

It is characteristic of the European family of nations, as distinguished from the other great divisions of mankind, that among them different ideals of government and of life arise from time to time, and that before the whole of a community has entirely adopted one set of principles, the more advanced thinkers are already passing on to another. Throughout the western part of continental Europe, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, absolute monarchy was superseding feudalism; and in France the victory of the newer over the older system was especially thorough. Then, suddenly, although not quite without warning, a third system was brought face to face with the two others. Democracy was born full-grown and defiant. It appealed at once to two sides of men's minds, to pure reason and to humanity. Why should a few men be allowed to rule a great multitude as deserving as themselves? Why should the mass of mankind lead lives full of labor and sorrow? These questions are difficult to answer. The Philosophers of the eighteenth century pronounced them unanswerable. They did not in all cases advise the establishment of democratic government as a cure for the wrongs which they saw in the world. But they attacked the things that were, proposing other things, more or less practicable, in their places. It seemed to these men no very difficult task to reconstitute society and civilization, if only the faulty arrangements of the past could be done away. They believed that men and things might be governed by a few simple laws, obvious and uniform. These natural laws they did not make any great effort to discover; they rather took them for granted; and while they disagreed in their statement of principles, they still believed their principles to be axiomatic. They therefore undertook to demolish simultaneously all established things which to their minds did not rest on absolute logical right. They bent themselves to their task with ardent faith and hope.

The larger number of people, who had been living quietly in the existing order, were amused and interested. The attacks of the Philosophers seemed to them just in many cases, the reasoning conclusive. But in their hearts they could not believe in the reality and importance of the assault. Some of those most interested in keeping the world as it was, honestly or frivolously joined in the cry for reform and for destruction.

At last an attempt was made to put the new theories into practice. The social edifice, slowly constructed through centuries, to meet the various needs of different generations, began to tumble about the astonished ears of its occupants. Then all who recognized that they had something at stake in civilization as it existed were startled and alarmed. Believers in the old religion, in old forms of government, in old manners and morals, men in fear for their heads and men in fear for their estates, were driven together. Absolutism and aristocracy, although entirely opposed to each other in principle, were forced into an unnatural alliance. From that day to this, the history of the world has been largely made up of the contests of the supporters of the new ideas, resting on natural law and on logic, with those of the older forms of thought and customs of life, having their sanctions in experience. It was in France that the long struggle began and took its form. It is therefore interesting to consider the government of that country, and its material and moral condition, at the time when the new ideas first became prominent and forced their way toward fulfillment.

It is seldom in the time of the generation in which they are propounded that new theories of life and its relations bear their full fruit. Only those doctrines which a man learns in his early youth seem to him so completely certain as to deserve to be pushed nearly to their last conclusions. The Frenchman of the reign of Louis XV. listened eagerly to Voltaire, Montesquieu and Rousseau. Their descendants, in the time of his grandson, first attempted to apply the ideas of those teachers. While I shall endeavor in this book to deal with social and political conditions existing in the reign of Louis XVI., I shall be obliged to turn to that of his predecessor for the origin of French thoughts which acted only in the last quarter of the century.

CHAPTER II.

LOUIS XVI. AND HIS COURT.

A centralized government, when it is well managed and carefully watched from above, may reach a degree of efficiency and quickness of action which a government of distributed local powers cannot hope to equal. But if a strong central government become disorganized, if inefficiency, or idleness, or, above all, dishonesty, once obtain a ruling place in it, the whole governing body is diseased. The honest men who may find themselves involved in any inferior part of the administration will either fall into discouraged acquiescence, or break their hearts and ruin their fortunes in hopeless revolt. Nothing but long years of untiring effort and inflexible will on the part of the ruler, with power to change his agents at his discretion, can restore order and honesty.

There is no doubt that the French administrative body at the time when Louis XVI. began to reign, was corrupt and self-seeking. In the management of the finances and of the army, illegitimate profits were made. But this was not the worst evil from which the public service was suffering. France was in fact governed by what in modern times is called "a ring." The members of such an organization pretend to serve the sovereign, or the public, and in some measure actually do so; but their rewards are determined by intrigue and favor, and are entirely disproportionate to their services. They generally prefer jobbery to direct stealing, and will spend a million of the state's money in a needless undertaking, in order to divert a few thousands into their own pockets.

They hold together against all the world, while trying to circumvent each other. Such a ring in old France was the court. By such a ring will every country be governed, where the sovereign who possesses the political power is weak in moral character or careless of the public interest; whether that sovereign be a monarch, a chamber, or the mass of the people.[Footnote: "Quand, dans un royaume, il y a plus d'avantage à faire sa cour qu'à faire son devoir, tout est perdu." Montesquieu, vii. 176, (Pensées diverses.)]

Louis XVI., king of France and of Navarre, was more dull than stupid, and weaker in will than in intellect. In him the hobbledehoy period had been unusually prolonged, and strangers at court were astonished to see a prince of nineteen years of age running after a footman to tickle him while his hands were full of dirty clothes.[Footnote: Swinburne, i. 11.] The clumsy youth grew up into a shy and awkward man, unable to find at will those accents of gracious politeness which are most useful to the great. Yet people who had been struck at first only with his awkwardness were sometimes astonished to find in him a certain amount of education, a memory for facts, and a reasonable judgment.[Footnote: Campan, ii. 231. Bertrand de Moleville, Histoire, i. Introd.; Mémoires, i. 221.] Among his predecessors he had set himself Henry IV. as a model, probably without any very accurate idea of the character of that monarch; and he had fully determined he would do what in him lay to make his people happy. He was, moreover, thoroughly conscientious, and had a high sense of the responsibility of his great calling. He was not indolent, although heavy, and his courage, which was sorely tested, was never broken. With these virtues he might have made a good king, had he possessed firmness of will enough to support a good minister, or to adhere to a good policy. But such strength had not been given him. Totally incapable of standing by himself, he leant successively, or simultaneously, on his aunt, his wife, his ministers, his courtiers, as ready to change his policy as his adviser. Yet it was part of his weakness to be unwilling to believe himself under the guidance of any particular person; he set a high value on his own authority, and was inordinately jealous of it. No one, therefore, could acquire a permanent influence. Thus a well-meaning man became the worst of sovereigns; for the first virtue of a master is consistency, and no subordinate can follow out with intelligent zeal today a policy which he knows may be subverted tomorrow.

The apologists of Louis XVI. are fond of speaking of him as "virtuous." The adjective is singularly ill-chosen. His faults were of the will more than of the understanding. To have a vague notion of what is right, to desire it in a general way, and to lack the moral force to do it,—surely this is the very opposite of virtue.

The French court, which was destined to have a very great influence on the course of events in this reign and in the beginning of the French Revolution, was composed of the people about the king's person. The royal family and the members of the higher nobility were admitted into the circle by right of birth, but a large place could be obtained only by favor. It was the court that controlled most appointments, for no king could know all applicants personally and intimately. The stream of honor and emolument from the royal fountain-head was diverted, by the ministers and courtiers, into their own channels. Louis XV had been led by his mistresses; Louis XVI was turned about by the last person who happened to speak to him. The courtiers, in their turn, were swayed by their feelings, or their interests. They formed parties and combinations, and intrigued for or against each other. They made bargains, they gave and took bribes. In all these intrigues, bribes, and bargains, the court ladies had a great share. They were as corrupt as the men, and as frivolous. It is probable that in no government did women ever exercise so great an influence.

The factions into which the court was divided tended to group themselves round certain rich and influential families. Such were the Noailles, an ambitious and powerful house, with which Lafayette was connected by marriage; the Broglies, one of whom had held the thread of the secret diplomacy which Louis XV. had carried on behind the backs of his acknowledged ministers; the Polignacs, new people, creatures of Queen Marie Antoinette; the Rohans, through the influence of whose great name an unworthy member of the family was to rise to high dignity in the church and the state, and then to cast a deep shadow on the darkening popularity of that ill-starred princess. Such families as these formed an upper class among nobles, and the members firmly believed in their own prescriptive right to the best places. The poorer nobility, on the other hand, saw with great jealousy the supremacy of the court families. They insisted that there was and should be but one order of nobility, all whose members were equal among themselves.[Footnote: See among other places the Instructions of the Nobility of Blois to the deputies, Archives parlementaires, ii. 385.]

The courtiers, on their side, thought themselves a different order of beings from the rest of the nation. The ceremony of presentation was the passport into their society, but by no means all who possessed this formal title were held to belong to the inner circle. Women who came to court but once a week, although of great family, were known as "Sunday ladies." The true courtier lived always in the refulgent presence of his sovereign.[Footnote: Campan, iii. 89.]

The court was considered a perfectly legitimate power, although much hated at times, and bearing, very properly, a large share of the odium of misgovernment. The idea of its legitimacy is impressed on the language of diplomacy, and we still speak of the Court of St. James, the Court of Vienna, as powers to be dealt with. Under a monarchy, people do not always distinguish in their own minds between the good of the state and the personal enjoyment of the monarch, nor is the doctrine that the king exists for his people by any means fully recognized. When the Count of Artois told the Parliament of Paris in 1787 that they knew that the expenses of the king could not be regulated by his receipts, but that his receipts must be governed by his expenses, he spoke a half-truth; yet it had probably not occurred to him that there was any difference between the necessity of keeping up an efficient army, and the desirability of having hounds, coaches, and palaces. He had not reflected that it might be essential to the honor of France to feed the old soldiers in the Hotel des Invalides, and quite superfluous to pay large sums to generals who had never taken the field and to colonels who seldom visited their regiments. The courtiers fully believed that to interfere with their salaries was to disturb the most sacred rights of property. In 1787, when the strictest economy was necessary, the king united his "Great Stables" and "Small Stables," throwing the Duke of Coigny, who had charge of the latter, out of place. Although great pains were taken to spare the duke's feelings and his pocket, he was very angry at the change, and there was a violent scene between him and the king. "We were really provoked, the Duke of Coigny and I," said Louis good-naturedly afterwards, "but I think if he had thrashed me, I should have forgiven him." The duke, however, was not so placable as the king. Holding another appointment, he resigned it in a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-002021-4 / 0000020214 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-002021-5 / 9780000020215 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 402 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich