The Art of War in Italy (eBook)

69 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-001989-9 (ISBN)

THE change from mediaeval to modern methods in the art of war is closely related to the general transformation of European civilization which goes by the name of the Renaissance. The revival of interest in ancient history and literature had a distinct effect on military theory and practice. The new spirit of inquiry and experiment applied itself vigorously to military problems. Moreover the avowed national separatism which replaced the sham imperialism of the Middle Ages accentuated the rivalry between states and produced wars which were more frequent, more prolonged, more general, and more intense than those of the preceding centuries. The history of these wars, waged in an age of eager intellectual activity, reveals, as we should expect it to reveal, rapid progress, amounting almost to revolution, in the use of arms, but what makes an examination of the subject singularly instructive is the fact that the most important of these campaigns were fought in Italy during the culminating years of the Italian Renaissance. The finest minds of the day had the opportunity of witnessing, of recording, and of commenting on the exploits of the leading captains and the most famous troops of Europe. They assisted in the interplay of ideas and the comparison of experiences. The fruit of this period of intensive cultivation of the art of war was the military science of the modern world.

STRATEGY

STRATEGY may be defined as a maneuvering before battle in order that your enemy may be found at a disadvantage when battle is joined. It is thus a means to an end. The ultimate object of every commander is to defeat his enemy in the field, but his ability to attain that object depends at least as much on the movements which precede battle as on tactical efficiency when battle is joined. Indeed in modern war the scene and the hour of the deciding action have often to be created by prolonged and painful effort, and it is sometimes the duty of a commander deliberately to postpone a decision until the situation become more favorable to his own chances of success. According to a master of contemporary warfare, it is this preliminary strategic maneuvering which calls forth the highest qualities of generalship. For commanders directing the strategy of a campaign he desiderates “an omnipresent sense of a great strategic objective and a power of patiently biding their time,” and further, “that highest of military gifts—the power of renunciation, of ‘cutting losses,’ of sacrificing the less essential for the more.” This strategic sense, this capacity to envisage maneuver and battle as equally vital parts of a comprehensive plan of campaign, was naturally less developed when war was more barbaric. In the Middle Ages, for instance, strategy existed only in a very rudimentary form. The commander of an army in the field regarded it as his primary duty to seek out the hostile force and to offer battle without delay. Elaborate preliminary maneuver was discountenanced both by the chivalric spirit of the age, which deprecated cunning in war, and by the desire of all feudal armies to return home as quickly as possible. When, however, professional soldiering began to replace feudal service, and when men began to take more interest in the wars of the ancient world than in the knightly ideals of their immediate past, neither the opportunity nor the means was lacking for a deeper study of the problems of strategy.

We have seen that this study first flourished among the Italian condottieri. By the end of the fifteenth century maneuver had acquired such importance in their eyes that it was practiced almost as an end in itself. Gian Paolo Vitelli and Prospero Colonna, two of the most famous of the condottieri of the period we are examining, were noted for their opinion that wars are won rather by industry and cunning than by the actual clash of arms. Their campaigns might be described with much justice as a painstaking avoidance of battle. In high contrast to this form of warfare are the methods of the invaders of Italy. The French especially are remarkable for their neglect of strategical principles, for their desire to close quickly with the enemy, and for the risks they run in the pursuit of that object. Each of these schools of strategy was tried and found wanting in the Italian wars, but each nevertheless made an important contribution towards the development of a more efficient strategical method. This new strategy is discernible in the Neapolitan campaigns of Gonsalvo, and its use by the imperialists is the determining cause of the final expulsion of the French from the peninsula. Its nature is illustrated by Francesco Guicciardini when he says that good soldiers are willing to retire repeatedly and to suffer delays in their pursuit of final victory, and by the biographer of Giovanni de’ Medici when he says that the armies of his day avoided each other till one of them had an advantage sufficient to make victory probable. In other words, maneuver was no longer despised, as it had been by mediaeval soldiers, nor was it made an end in itself, after the manner of the condottieri. It was essential in so far as it helped towards the attainment of the “great strategic objective"—the delivery of a final shattering blow at the enemy. The recognition of this truth marks the beginning of modern strategy.

From the strategic point of view the Italian wars which were brought to an end in 1529 fall into four groups. There is first of all the French bid for Naples, which is opposed by Spain and which results in the subjugation of the Neapolitan kingdom by the Spanish monarchy in 1503. The second series of wars begins with the French conquest of the Duchy of Milan in 1499, is continued ten years later by a coalition against Venice which pushes French influence still further eastward, and is brought to a close in 1512 by the expulsion of the French from Italy. Then follow five efforts on the part of France to regain a footing in northern Italy: one of these efforts achieves a temporary success by Francis I’s victory at Marignano in 1515, but the decisive defeat of the same monarch at Pavia in 1525 marks the final frustration of French ambitions beyond the Alps. As a pendant to these three groups of campaigns there is an unsuccessful invasion of Naples by the French in 1527, followed by an equally unsuccessful invasion of Lombardy in 1528.

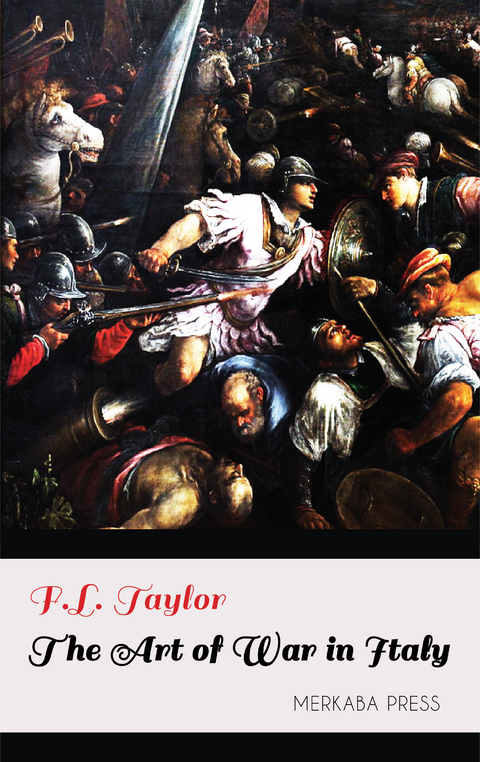

A BATTLE SCENE DEPICTING THE FRENCH CONQUEST OF NAPLES

Charles VIII’s conquest of Naples in 1495 was a triumph of the mediaeval method of direct attack over the fashionable Italian method of maneuver and delay. Ferdinand, king of Naples, refused to fight in the field and preferred to distribute his army among a number of fortresses, in the hope that their, resistance would give time for political forces to come into play on his side. But the new French siege artillery mastered the Italian fortresses with surprising swiftness, and within a few weeks Ferdinand was an exile from his kingdom. Strategically, however, Charles’s position in Naples was very vulnerable.

The presence of hostile states in northern Italy was a constant threat to his communications both by land and sea, and though the cutting of an enemy’s communications did not at that period produce the immediate decision which it does to-day (since a large proportion of the ammunition and food supply was purchased locally), nevertheless an army barring the path back to France and a fleet commanding the Tyrrhene Sea could between them have subdued the French army by slow strangulation. The rulers of Milan and Venice, who headed the combination against Charles, were in a position to take both these measures: yet they restricted their maritime activities to the support of Neapolitan rebels, and gave the command of their army to a soldier who did not understand how to make use of a natural obstacle. The battle of Fornovo, by which Charles forced his way past the enemy who stood in his path, was not an indecisive action but a definite victory for France. It enabled Charles to gain his strategic objective— junction with his base at Asti—and by that success to wreck the plans of his enemies. The marquis of Mantua, who was responsible for the operations of the Italian army, could have stopped the French dead by holding the defiles of the Apennines. Instead, he allowed them to debouch into the plain, and to rest after their difficult passage of the mountains, before he delivered his elaborate but ineffective attack. It is interesting to note that one of his motives for delaying the attack was a chivalrous sympathy for a foe in difficulties. In this first campaign of the Italian wars we are certainly a long way from modern strategy.

Guicciardini says very justly that the lesson of Charles VIII’s expedition was that the commander who could not resist in the open field had no hope of defending himself at all. This moral was not drawn by those whom it touched most closely. When in 1501 the French and the Spanish made their combined attack on Naples we find King Federigo repeating the mistakes of his predecessor, using his army to garrison fortresses, and consequently losing his kingdom to the guns of the enemy. Very different is the strategy by which in the following years Gonsalvo de Cordova destroyed the French armies and added the kingdom of Naples to the crown of Spain. At the opening of the struggle with the French Gonsalvo was inferior to the enemy in men, in money, in food supplies, and in munitions. He therefore retired to the seaport of Barletta, which he protected on the land-side by strong field defenses, and whence by sea he could communicate with Spain, with Sicily, and with his Venetian allies. His sole object in retiring to Barletta was to wait until his army was sufficiently reinforced and re-equipped to enable him to take the offensive. Though biding his time he was never passive. He maintained the moral of his troops by frequent sorties; by personal effort he borrowed money for clothing and paying them; fresh drafts were raised from Germany and the Papal states by the vigorous recruiting of his emissaries. He refused to listen to a well-founded rumor that the French and the Spanish kings had concluded a truce, and when his reinforcements at last arrived he issued from his fortifications, defeated the enemy at Cerignola, and became in a few weeks master of the kingdom.

Later in the same year, by the arrival from France of a fresh army of invasion, Gonsalvo found himself again outnumbered and reduced to the defensive. He barred the road to Naples by holding the obstacle of the river Garigliano. Reacting fiercely to the French effort to cross, he succeeded in confining them to a small bridgehead. The approach of winter induced the French first to suspend operations, and then to distribute the greater part of their army far from the river. Gonsalvo likewise withdrew most of his men to more comfortable quarters, but the arrival of reinforcements decided him to take the offensive at once and in spite of the season....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-001989-5 / 0000019895 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-001989-9 / 9780000019899 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 462 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich